National

Teachers with Subconscious Bias Punish Blacks More Severely

“We discovered, the more likely teachers thought a student was Black, the more harshly they wanted to punish them,” said Jason Okonofua, a doctoral student at Stanford University and co-author of the study, “Two Strikes: Race and the Disciplining of Young Students.” (Courtesy Photo)

By Jazelle Hunt

NNPA Washington Correspondent

WASHINGTON (NNPA) – When teachers harbor subconscious racial bias, they are far more likely to discipline White students less severely than African Americans, according to a new study.

As early as kindergarten, Black girls are being suspended at six times the rate of White girls, and more than all boys except fellow African Americans. Black boys are being suspended at three times the rate of White boys. According to 2010 figures from the Department’s Civil Rights Data Collection, 44 percent of those suspended more than once that year, and 36 percent of those expelled were Black – despite being less than 20 percent of the student population.

“Stereotypes serve as sort of a glue that sticks separate encounters together in our mind and lead us to then respond more negatively,” says Jason Okonofua, doctoral student at Stanford University and co-author of the study, “Two Strikes: Race and the Disciplining of Young Students.”

“In the study we have…the stereotype that the student is a ‘troublemaker’ leads the teacher to see two separate instances of misbehavior as constituting a pattern. Therefore following the second misbehavior there’s a sharp escalation in how severely the teacher wants to discipline a Black child.”

This is known as the “Black escalation effect.” As the number of behavioral issues increases, it is perceived as more of a threat to the classroom if the doer is Black. Black escalation leads teachers to discipline Black students faster and more harshly than their White counterparts, even when the students have the same number and types of offenses.

In the study, which appears in the April issue of Psychological Science, 53 teachers, all women, mostly White, were given a school record for a hypothetical student. Each record detailed two minor misbehaviors (classroom disruption and insubordination) – some for a hypothetical child named Darnell or Deshawn, others for a hypothetical child named Jake or Greg.

On average, teachers responded the same way to Darnell, Deshawn, Greg, and Jake on their first misbehaviors. But on the second offense, they were more likely to punish the boys they perceived as Black, more likely to issue harsher punishments to them, and more likely to label them “troublemakers.”

All of the participants were current K-12 teachers with an average of 14 years of experience.

“We discovered, the more likely teachers thought a student was Black, the more harshly they wanted to punish them,” Okonofua says. “That’s surprising because all we manipulated in the study was the names. But it’s not just the student’s name, it’s the level of Blackness teachers think the student is.”

The teachers in the study also reported feeling “more troubled” over second offenses when they perceived the student as Black (also by their own report). Further, when the students were perceived as Black, the teachers were more likely to report that they could see themselves suspending him in the future.

Stereotypes largely drive the Black escalation effect. Black children are more likely to be stereotyped as aggressive, defiant, and learning-disabled; when Black children misbehave and are disciplined, these stereotypes can kick in and result in harsher reactions.

Okonofua says, “Most school teachers work hard at treating their students equally. And yet, even among these well-intentioned and hardworking people, we find that cultural stereotypes about Black people are bending people’s perceptions toward less favorable interpretations of Black students’ behavior.”

The Department of Education estimates that 2014 was the first year students of color and White students reached equal numbers in the nation’s elementary and middle schools. Among kids under 5 years old, children of color are already the majority.

Most teacher training programs are not equipped to prepare future teachers for the realities of multiracial classrooms. But some programs have begun to recognize the impact this has on educational outcomes for the nation’s students of color.

“Part of the challenge of this is, for racial bias to even be brought to the table it requires a certain level of racial consciousness on the part of the teacher educator,” said Tyrone Howard, professor of education at University of California, Los Angeles.

“Ninety percent of all teacher educators are White. And by and large, most White people don’t think about issues of race.”

In addition to training teachers, Howard serves as the founding director of UCLA’s Black Male Institute to improve educational outcomes for Black boys, as well as the faculty director of UCLA Center X, a program that cultivates social justice-minded teachers for low-income Los Angeles public schools.

In his experience, White aspiring teachers tend to be uncomfortable or annoyed when he brings racism, stereotypes, and bias into his instruction. Meanwhile, he says, aspiring teachers of color often feel marginalized and unprepared for classrooms when their training programs avoid discussions on race.

“When I was in the Midwest, where the majority of my [education] students were White, there’s oftentimes a reticence to engage in that work while they’re in the program,” he says, adding that he was often told he made White people uncomfortable. “But once they’ve had the opportunity to understand that race is ever-present and that students of color are always watchful of what they say, what they do, and how they act…then [teachers] begin to see ‘Wow, I didn’t realize these issues were real.’”

Another challenge is that few programs have a system in place to verify whether their anti-bias training is effective once education students enter real classrooms.

But such programs are the exception. Most teachers receive little to no discussion or training on these issues – and in most states, this has no bearing on the requirements for earning teaching credentials.

For teachers who lack access to adequate anti-bias, anti-racist training, Okonofua has found through other research that refocusing on maintaining warm relationships with each student weakens the effect of subconscious biases.

Howard believes that without formal interventions, the effort to make teachers more culturally competent and will be too little, too late.

He says: “As long as states and credentialing commissions don’t make this a staple of what is required for credentials, it will always be looked at as optional or it will always be on the fringes.”

###

Activism

Oakland Post: Week of December 25 – 31, 2024

The printed Weekly Edition of the Oakland Post: Week of December 25 – 31, 2024

To enlarge your view of this issue, use the slider, magnifying glass icon or full page icon in the lower right corner of the browser window. ![]()

Activism

OPINION: “My Girl,” The Temptations, and Nikki Giovanni

Giovanni was probably one of the most famous young African American women in the 1960s, known for her fiery poetry. But even that description is tame. The New York Times obit headline practically buried her historical impact: “Nikki Giovanni, Poet Who Wrote of Black Joy, Dies at 81.” That doesn’t begin to touch the fire of Giovanni’s work through her lifetime.

By Emil Guillermo

The Temptations, the harmonizing, singing dancing man-group of your OG youth, were on “The Today Show,” earlier this week.

There were some new members, no David Ruffin. But Otis Williams, 83, was there still crooning and preening, leading the group’s 60th anniversary performance of “My Girl.”

When I first heard “My Girl,” I got it.

I was 9 and had a crush on Julie Satterfield, with the braided ponytails in my catechism class. Unfortunately, she did not become my girl.

But that song was always a special bridge in my life. In college, I was a member of a practically all-White, all-male club that mirrored the demographics at that university. At the parties, the song of choice was “My Girl.”

Which is odd, because the party was 98% men.

The organization is a little better now, with women, people of color and LGBTQ+, but back in the 70s, the Tempts music was the only thing that integrated that club.

POETRY’S “MY GIRL”

The song’s anniversary took me by surprise. But not as much as the death of Nikki Giovanni.

Giovanni was probably one of the most famous young African American women in the 1960s, known for her fiery poetry. But even that description is tame.

The New York Times obit headline practically buried her historical impact: “Nikki Giovanni, Poet Who Wrote of Black Joy, Dies at 81.”

That doesn’t begin to touch the fire of Giovanni’s work through her lifetime.

I’ll always see her as the Black female voice that broke through the silence of good enough. In 1968, when cities were burning all across America, Giovanni was the militant female voice of a revolution.

Her “The True Import of Present Dialogue: Black vs. Negro,” is the historical record of racial anger as literature from the opening lines.

It reads profane and violent, shockingly so then. These days, it may seem tamer than rap music.

But it’s jarring and pulls no punches. It protests Vietnam, and what Black men were asked to do for their country.

“We kill in Viet Nam,” she wrote. “We kill for UN & NATO & SEATO & US.”

Written in 1968, it was a poem that spoke to the militancy and activism of the times. And she explained herself in a follow up, “My Poem.”

“I am 25 years old, Black female poet,” she wrote referring to her earlier controversial poem. “If they kill me. It won’t stop the revolution.”

Giovanni wrote more poetry and children’s books. She taught at Rutgers, then later Virginia Tech where she followed her fellow professor who would become her spouse, Virginia C. Fowler.

Since Giovanni’s death, I’ve read through her poetry, from what made her famous, to her later poems that revealed her humanity and compassion for all of life.

In “Allowables,” she writes of finding a spider on a book, then killing it.

And she scared me

And I smashed her

I don’t think

I’m allowed

To kill something

Because I am

Frightened

For Giovanni, her soul was in her poetry, and the revolution was her evolution.

About the Author

Emil Guillermo is a journalist, commentator, and solo performer. Join him at www.patreon.com/emilamok

Black History

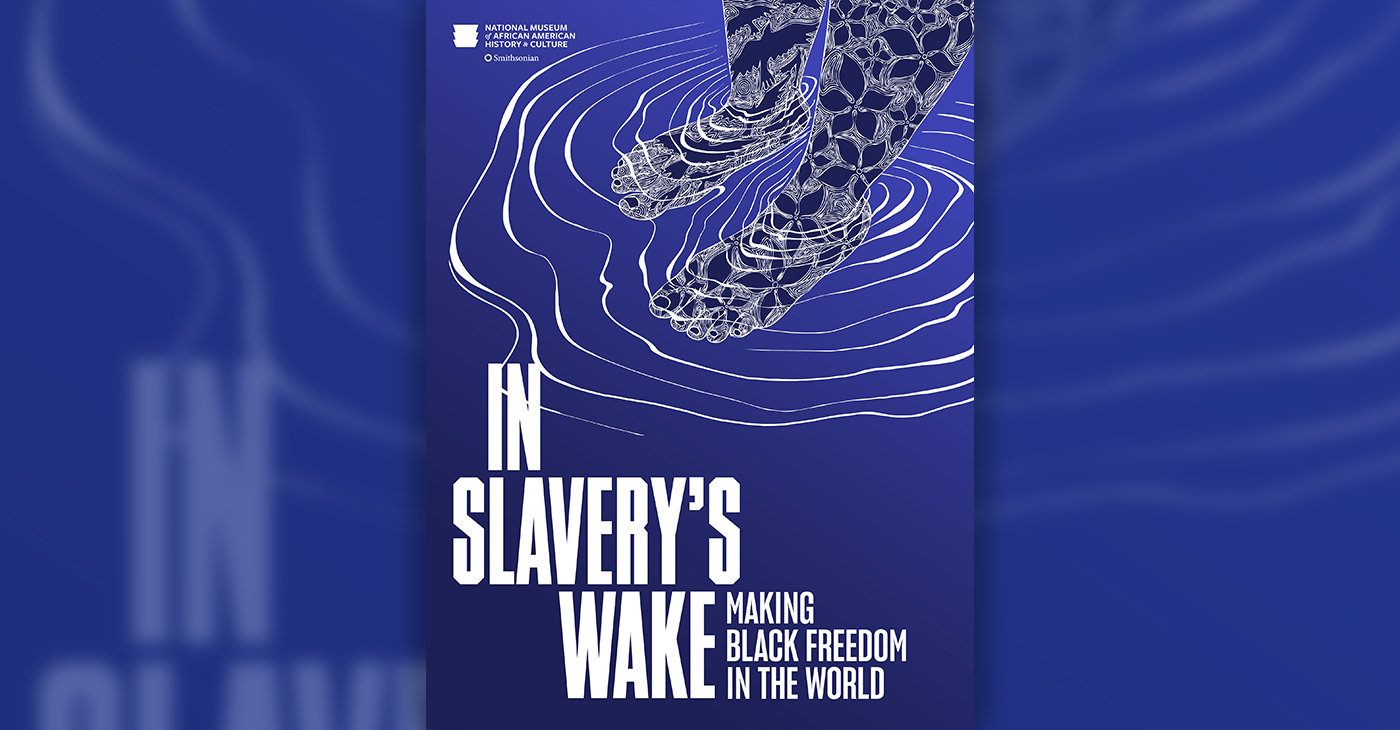

Book Review: In Slavery’s Wake: Making Black Freedom in the World

It’s a tale of heroes: the Maroons, who created communities in unwanted swampland, and welcomed escaped slaves into their midst; Sarah Baartman, the “Hottentot Venus”; Marème Diarra, who walked more than 2000 miles from Sudan to Senegal with her children to escape slavery; enslaved farmers and horticulturists; and everyday people who still talk about slavery and what the institution left behind.

By Terri Schlichenmeyer

Ever since you learned how it happened you couldn’t get it out of your mind.

People, packed like pencils in a box, tightly next to each other, one by one by one, tier after tier. They couldn’t sit up, couldn’t roll over or scratch an itch or keep themselves clean on a ship that took them from one terrible thing to another. And in the new book “In Slavery’s Wake,” essays by various contributors, you’ll see what trailed in waves behind those vessels.

You don’t need to be told about the horrors of slavery. You’ve grown up knowing about it, reading about it, thinking about everything that’s happened because of it in the past four hundred years. And so have others: in 2014, a committee made of “key staff from several world museums” gathered to discuss “telling the story of racial slavery and colonialism as a world system…” so that together, they could implement a “ten-year road map to expand… our practices of truth telling…”

Here, the effects of slavery are compared to the waves left by a moving ship, a wake the story of which some have tried over time to diminish.

It’s a tale filled with irony. Says one contributor, early American Colonists held enslaved people but believed that King George had “unjustly enslaved” the colonists.

It’s the story of a British company that crafted shackles and cuffs and that still sells handcuffs “used worldwide by police and militaries” today.

It’s a tale of heroes: the Maroons, who created communities in unwanted swampland, and welcomed escaped slaves into their midst; Sarah Baartman, the “Hottentot Venus”; Marème Diarra, who walked more than 2000 miles from Sudan to Senegal with her children to escape slavery; enslaved farmers and horticulturists; and everyday people who still talk about slavery and what the institution left behind.

Today, discussions about cooperation and diversity remain essential.

Says one essayist, “… embracing a view of history with a more expansive definition of archives in all their forms must be fostered in all societies.”

Unless you’ve been completely unaware and haven’t been paying attention for the past 150 years, a great deal of what you’ll read inside “In Slavery’s Wake” is information you already knew and images you’ve already seen.

Look again, though, because this comprehensive book isn’t just about America and its history. It’s about slavery, worldwide, yesterday and today.

Casual readers – non-historians especially – will, in fact, be surprised to learn, then, about slavery on other continents, how Africans left their legacies in places far from home, and how the “wake” they left changed the worlds of agriculture, music, and culture. Tales of individual people round out the narrative, in legends that melt into the stories of others and present new heroes, activists, resisters, allies, and tales that are inspirational and thrilling.

This book is sometimes a difficult read and is probably best consumed in small bites that can be considered with great care to appreciate fully. Start “In Slavery’s Wake,” though, and you won’t be able to get it out of your mind.

Edited by Paul Gardullo, Johanna Obenda, and Anthony Bogues, Author: Various Contributors, c.2024, Smithsonian Books, $39.95

-

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of November 27 – December 3, 2024

-

Activism2 weeks ago

Activism2 weeks agoButler, Lee Celebrate Passage of Bill to Honor Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm with Congressional Gold Medal

-

Activism2 weeks ago

Activism2 weeks agoPost News Group to Host Second Town Hall on Racism, Hate Crimes

-

Activism2 weeks ago

Activism2 weeks agoDelta Sigma Theta Alumnae Chapters Host World AIDS Day Event

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoLandlords Are Using AI to Raise Rents — And California Cities Are Leading the Pushback

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of December 4 – 10, 2024

-

Activism2 weeks ago

Activism2 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of December 11 – 17, 2024

-

Arts and Culture1 week ago

Arts and Culture1 week agoPromise Marks Performs Songs of Etta James in One-Woman Show, “A Sunday Kind of Love” at the Black Repertory Theater in Berkeley