Books

Poet James Cagney on Closure, Reckoning’s Limits, and What’s Next

Oakland poet James Cagney was 19 when he asked his mother “Are you really my mother?” Her answer changed his life forever. He learned he was adopted, that his birth parents, who already had seven children, couldn’t afford to raise him.

Oakland poet James Cagney was 19 when he asked his mother “Are you really my mother?” Her answer changed his life forever. He learned he was adopted, that his birth parents, who already had seven children, couldn’t afford to raise him.

As a baby, Cagney had been given to an older couple who raised him. His adoptive mother had been his birth mother’s teacher in cosmetology school. The women knew each other well, but Cagney never knew his birth family as a child.

Cagney grew up as an only child in North Oakland and forged a close, loving relationship with his mother. But things were different with the man who raised him. While Cagney has emphasized that his father wasn’t abusive, his parenting was passive and detached. In his poem “Someone Else’s Child,” Cagney asks “Did you ever hold me as a baby?” to which his father answers “Naw. ‘fraid I’d drop you. ‘sides. You were someone/else’s child.”

After learning about his adoption, Cagney’s life would become even more turbulent in about the next dozen years. During that time, the parents who raised him died. Then there was the literal earth shaking, the 1994 Northridge Earthquake, contributed to him losing the home he grew up in, and he became homeless.

He bounced around as a guest in friend’s homes, lived in an SRO, and most notably, lived with his birth mother in Sacramento for about two years. He forged complex, difficult, but ultimately rewarding and loving relationships with much of his birth family, but he never got to meet his birth father, who died before Cagney even knew he existed.

He began penning deeply autobiographical poetry about his familial experiences. It would take him about 20 years to write and collect this poetry into his first book, “Black Steel Magnolias in the Hour of Chaos Theory.” He was 50 when the Oakland-based Nomadic Press published it in 2018.

Since then, he’s become a celebrated and widely read poet. “Black Steel Magnolias in the Hour of Chaos Theory” sold out of its first print run and Nomadic Press just reissued it in a second printing with a new foreward and introduction. His next book, “Martian: The Saint of Loneliness,” just won the James Laughlin Award from the Academy of American Poets. Nomadic Press will publish it fall of 2022.

I talked with Cagney, now 53 and living in East Oakland, about his experience writing and publishing “Black Steel Magnolias in the Hour of Chaos Theory.” We also talked a little bit about “Martian: The Saint of Loneliness,” which, in taking a turn away from autobiography, expands his poetics. I edited our conversation for readability and brevity.

Zack: It’s been over three years since “Black Steel Magnolias in the Hour of Chaos Theory” was published. How has the book’s publication and its reception affected your process of dealing with the difficult experiences the book addresses?

Cagney: More than anything it allowed me closure. Up until the time I decided to publish all that material, I was feeling that my story was so personal it didn’t feel like it was necessary or a goal to share it. I didn’t think a lot of other people would have empathy for my sort of weird, broken family thing. I didn’t feel like my story had enough drama to attract a lot of attention. My family was not nasty. I mention alcoholism in the book but it’s not like my father was a maniac. I was very fortunate and blessed. So, the book was mostly just me trying to sort out my own identity in the wake of all that confusing craziness.

I decided to publish the book just to provide what I would have liked to have seen in the world when I was younger. I wanted to communicate to people who have had similar weird family experiences. I also wanted to acknowledge the love and respect a lot of people in the poetry community have paid me over the years. Many people have been very respectful and responsive to the poems that I’ve done. And especially with the proximity and the newness of Nomadic Press, I decided to go forward, publish all that stuff, and just get it out of my head.

The most important part was claiming space for myself in poetry by validating my own life through these pieces that represented who I was and where I came from. I gambled on the love other people had shared with me by sending it out into the world to see what would happen.

But to be honest, Zack, nothing has shifted (laughter) because especially with the pandemic and being under house arrest for a year, the alienation has never gone away. When I think of the disconnection that made the poems exist, I guess I could confess to you that feeling persists. I’ve just gotten used to the weight and tension of it. It’s sort of like walking a dog that wants to pull you as opposed to walk with you is what my issues feel like sometimes. I still feel like I’m wrestling and settling with that.

I wish I could tell you something has changed, or a new sun has risen over a different land. But the way I felt writing those poems, I unfortunately still feel that way. I just feel a little bit better about it. I feel I’ve matured with it. I feel I’ve accepted more of it instead of fighting and whining against the way things just happen to be. I also feel really grateful for the response the book has gotten. I feel good closing a particular chapter of my life. I guess that book represents the first third of my life: my childhood and early adulthood. What that book does is validate I was here, and I survived. And maybe that’s enough.

Zack: To me, Black Steel Magnolias in the Hour of Chaos Theory reads like poetic autobiography in the present tense by continually addressing the past as it relates to the now. But since the book took about 20 years to write, you and that now shift dramatically in different poems. What does 20 years do? How did that duration affect how the book took shape?

Cagney: It’s interesting for me to take a look at the book as a whole and see the poems that were started in the mid-’90s and poems that I wrote in the year before it got published, to see that conversation and growth. I guess those are like two different Jameses. The earlier James was still trying to figure things out and was maybe overwriting and working too hard to create poetic images and stuff like that. When I was in high school, I studied journalism and almost took that up as a career. What that platform gave me, in those early years, was a sense of trying to interrogate the truth as I had been taught to find it through journalism to then create a structure and framework for that truth that I was gradually learning from open mics and reading books. The more current James has been introduced to experimentation and gotten the point of compression. I push the story into a smaller space and am able to be more experimental by making strange, unusual decisions; and I don’t feel I have to be so strict with the truth.

The book represents a serious, huge growth period for me as much as it does negotiating of family. I can see the old and new James in conversation and trying to balance themselves. It’s finding a balance between my older mindse,t which is more much raw in trying to figure myself out and what poetry is and can do, and now me, many years later, having gone through this process of family and identity and poetry and applying much stricter edits and purpose in the kind of poems I’m trying to create.

Often “Black Steel Magnolias in the Hour of Chaos Theory” feels palpably unresolved to me, like the pain of holding one’s breath. I like that because it helps me relate to what’s happening in the book, which often seems to be about not being able to find peace or finding incomplete peace. It makes me curious about your forthcoming book, “Martian: The Saint of Loneliness.” Is that book a continuation of the themes of its predecessor? How is it different from its predecessor? What would you like to share with readers about it?

I told my editor, Michaela Mullin, who worked on both books, that “Black Steel Magnolias in the Hour of Chaos Theory” is who I am, and “Martian: The Saint of Loneliness” represents what I do as a poet. There are themes in “Martian” that absolutely converse with what happens in the first book, but this collection is very different. I guess I just wanted to get all my biographical stuff out of the way in “Black Steel Magnolias”. In “Martian,” I address a lot of race issues, the history of America, Black Lives Matter, as well as love poems and meditations on my feelings of isolation nonetheless.

Part of the image I’m looking at for “Martian” is that there’s a lot of families who have lost people to gun violence and racial violence. We often call the names and talk about those who are lost. One thing the book does, in an indirect way, is it pays attention to the people who are still here and have to hold that loss. What questions would you have for Trayvon Martin’s best friend? What is the story of the feelings people have about the disappearance that their friend or brother or sister leaves after being murdered by police or dying through COVID?

I’m familiar with grief from the last book. Maybe this next book tries to look into the hole that grief has left and ask: what do we do now with this space, this darkness, with what’s left by this person’s invisibility? What happens now?

The Oakland Post’s coverage of local news in Alameda County is supported by the Ethnic Media Sustainability Initiative, a program created by California Black Media and Ethnic Media Services to support community newspapers across California.

Activism

Oakland Post: Week of January 8 – 14, 2025

The printed Weekly Edition of the Oakland Post: Week of January 8 – 14, 2025

To enlarge your view of this issue, use the slider, magnifying glass icon or full page icon in the lower right corner of the browser window.

Arts and Culture

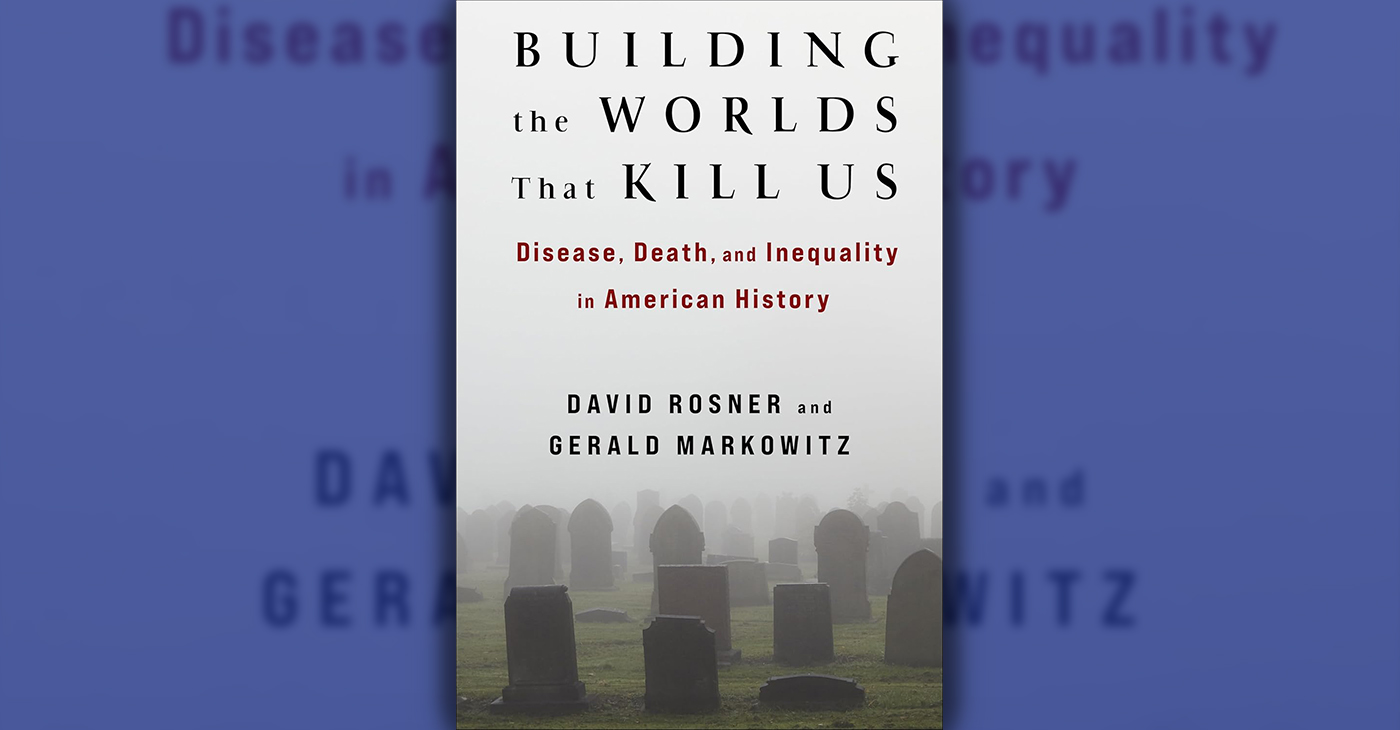

Book Review: Building the Worlds That Kill Us: Disease, Death, and Inequality in American History

Nearly five years ago, while interviewing residents along the Mississippi River in Louisiana for a book they were writing, authors Rosner and Markowitz learned that they’d caused a little brouhaha. Large corporations in the area, ones that the residents of “a small, largely African American community” had battled over air and soil contamination and illness, didn’t want any more “’agitators’” poking around. They’d asked a state trooper to see if the authors were going to cause trouble.

By Terri Schlichenmeyer

Author: David Rosner and Gerald Markowitz, c.2024, Columbia University Press, $28.00

Get lots of rest.

That’s always good advice when you’re ailing. Don’t overdo. Don’t try to be Superman or Supermom, just rest and follow your doctor’s orders.

And if, as in the new book, “Building the Worlds That Kill Us” by David Rosner and Gerald Markowitz, the color of your skin and your social strata are a certain way, you’ll feel better soon.

Nearly five years ago, while interviewing residents along the Mississippi River in Louisiana for a book they were writing, authors Rosner and Markowitz learned that they’d caused a little brouhaha. Large corporations in the area, ones that the residents of “a small, largely African American community” had battled over air and soil contamination and illness, didn’t want any more “’agitators’” poking around. They’d asked a state trooper to see if the authors were going to cause trouble.

For Rosner and Markowitz, this underscored “what every thoughtful person at least suspects”: that age, geography, immigrant status, “income, wealth, race, gender, sexuality, and social position” largely impacts the quality and availability of medical care.

It’s been this way since Europeans first arrived on North American shores.

Native Americans “had their share of illness and disease” even before the Europeans arrived and brought diseases that decimated established populations. There was little-to-no medicine offered to slaves on the Middle Passage because a ship owner’s “financial calculus… included the price of disease and death.” According to the authors, many enslavers weren’t even “convinced” that the cost of feeding their slaves was worth the work received.

Factory workers in the late 1800s and early 1900s worked long weeks and long days under sometimes dangerous conditions, and health care was meager; Depression-era workers didn’t fare much better. Black Americans were used for medical experimentation. And just three years ago, the American Lung Association reported that “’people of color’ disproportionately” lived in areas where the air quality was particularly dangerous.

So, what does all this mean? Authors David Rosner and Gerald Markowitz don’t seem to be too optimistic, for one thing, but in “Building the Worlds That Kill Us,” they do leave readers with a thought-provoker: “we as a nation … created this dark moment and we have the ability to change it.” Finding the “how” in this book, however, will take serious between-the-lines reading.

If that sounds ominous, it is. Most of this book is, in fact, quite dismaying, despite that there are glimpses of pushback here and there, in the form of protests and strikes throughout many decades. You may notice, if this is a subject you’re passionate about, that the histories may be familiar but deeper than you might’ve learned in high school. You’ll also notice the relevance to today’s healthcare issues and questions, and that’s likewise disturbing.

This is by no means a happy-happy vacation book, but it is essential reading if you care about national health issues, worker safety, public attitudes, and government involvement in medical care inequality. You may know some of what’s inside “Building the Worlds That Kill Us,” but now you can learn the rest.

Activism

Oakland Post: Week of January 1 – 7, 2025

The printed Weekly Edition of the Oakland Post: Week of January 1 – 7, 2025

To enlarge your view of this issue, use the slider, magnifying glass icon or full page icon in the lower right corner of the browser window.

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoBooks for Ghana

-

Arts and Culture4 weeks ago

Arts and Culture4 weeks agoPromise Marks Performs Songs of Etta James in One-Woman Show, “A Sunday Kind of Love” at the Black Repertory Theater in Berkeley

-

Bay Area3 weeks ago

Bay Area3 weeks agoGlydways Breaking Ground on 14-Acre Demonstration Facility at Hilltop Mall

-

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks ago‘Donald Trump Is Not a God:’ Rep. Bennie Thompson Blasts Trump’s Call to Jail Him

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoLiving His Legacy: The Late Oscar Wright’s “Village” Vows to Inherit Activist’s Commitment to Education

-

Arts and Culture3 weeks ago

Arts and Culture3 weeks agoIn ‘Affrilachia: Testimonies,’ Puts Blacks in Appalacia on the Map

-

Alameda County3 weeks ago

Alameda County3 weeks agoAC Transit Holiday Bus Offering Free Rides Since 1963

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoCalifornia, Districts Try to Recruit and Retain Black Teachers; Advocates Say More Should Be Done