Book Reviews

“Lucky Medicine” by Lester W. Thompson

It didn’t arrive in a package. It wasn’t wrapped in fancy paper. It didn’t arrive with cake or candles. And yet, the gift you got, that thing that someone gave you was better than anything that could’ve come in a pretty box. It was bigger than you ever expected. As in the new memoir, “Lucky Medicine” by Lester W. Thompson, the gift was a life-changer.

c.2023, Well House Books, Indiana University Press $24.00 196 pages

It didn’t arrive in a package.

It wasn’t wrapped in fancy paper. It didn’t arrive with cake or candles. And yet, the gift you got, that thing that someone gave you was better than anything that could’ve come in a pretty box. It was bigger than you ever expected. As in the new memoir, “Lucky Medicine” by Lester W. Thompson, the gift was a life-changer.

Born and raised in Indianapolis, Lester Thompson grew up with “rules” that his Southern-born parents instilled in him all his life. Even though Jim Crow racism wasn’t entrenched in the North like it was in the South, such rules were “the frame of reference.”

And that lent mystery to a very curious relationship Thompson’s father had with a white Jewish man, Mr. Goodman. Cal Thompson cut Goodman’s hair in the privacy of Goodman’s home; Thompson sometimes accompanied his father there, but he never fully understood the friendship between the two men. He says “It didn’t occur to me to wonder…”

When he was thirteen, he learned the truth: he was named after Goodman, who was his father’s closest friend. Furthermore, Goodman was Thompson’s godfather and he’d made a vow to pay for Thompson’s entire college education.

That he was going to be a doctor someday was another thing Thompson had known all his life. His father, an authoritarian alcoholic, never left any room to question it. And so, after high school graduation, Thompson headed to IU in Bloomington, Indiana.

It was an eye-opener, in many ways.

An only child, Thompson had to learn how to share. He had to learn to live with white people next door, and how to study for classes that seemed impossible to ace. He fell in love, and fell again. And he watched the world change as the Civil Rights Movement began.

“I will never know what prompted Mr. Goodman to make his gift,” Thompson says. “But in the end, I suppose, all that matters is that he did.”

Sometimes, change can come with a big ka-BOOM. Other times, it sneaks in the back door and sits quietly. That mixture’s what you get with this unique memoir, “Lucky Medicine.”

Unique because while racism figures into author Lester W. Thompson’s story, it’s not a very big part, considering the mid-last-century setting. The Movement is barely a blip on the radar; only a handful of troubles with white people are mentioned, and they’re not belabored. So, racism is in this book, but only at whisper-level.

Instead, Thompson focuses on his relatively insulated life, his parents and friends, his studies, and the mysterious, still-unsolved relationship his father had with Goodman. And that’s where this story glows: Thompson’s tale is nostalgic and mundane. It’s not overly dramatic. It doesn’t shout or beg for attention. It’s just warm and happily, wonderfully, ordinary.

Be aware before you share this book with an elder that there are four-letter words in here and a rather eyebrow-raising, too-much-information bedroom scene inside. If you can handle that, though, “Lucky Medicine” is a one-of-a-kind gift.

Activism

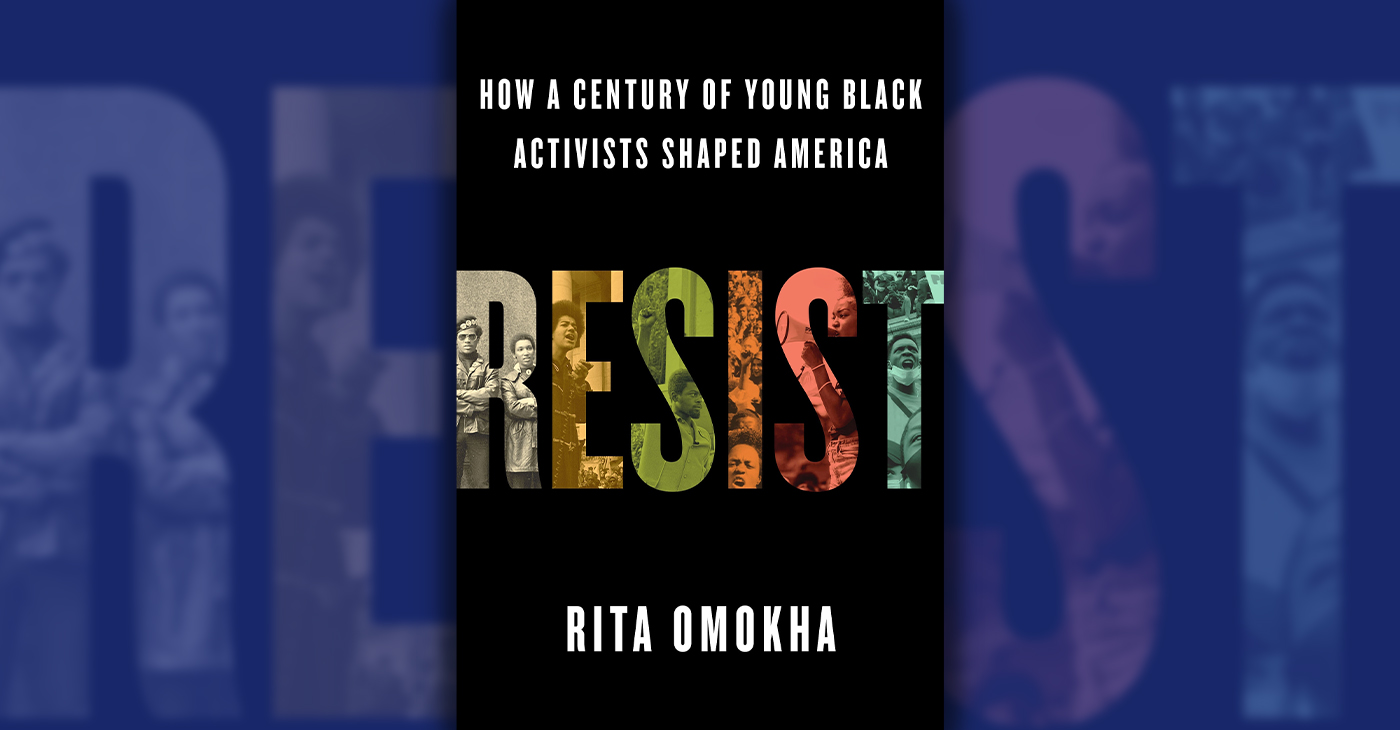

‘Resist’ a Look at Black Activism in U.S. Through the Eyes of a Native Nigerian

In 1995, after she and her brothers traveled from their native Nigeria to join their mother at her new home in the South Bronx, young Omokha’s eyes were opened. She quickly understood that the color of her skin – which was “synonymous with endless striving and a pursuit of excellence” in Nigeria – was “so problematic in America.”

By Terri Schlichenmeyer, The Bookworm Sez

Throughout history, when decisions were needed, the answer has often been “no.”

‘No,’ certain people don’t get the same education as others. ‘No,’ there is no such thing as equality. ‘No,’ voting can be denied and ‘no,’ the laws are different, depending on the color of one’s skin. And in the new book, “Resist!” by Rita Omokha, ‘no,’ there is not an obedient acceptance of those things.

In 1995, after she and her brothers traveled from their native Nigeria to join their mother at her new home in the South Bronx, young Omokha’s eyes were opened. She quickly understood that the color of her skin – which was “synonymous with endless striving and a pursuit of excellence” in Nigeria – was “so problematic in America.”

That became a bigger matter to Omokha later, 15 years after her brother was deported: she “saw” him in George Floyd, and it shook her. Troubled, she traveled to America on a “pilgrimage for understanding [her] Blackness…” She began to think about the “Black young people across America” who hadn’t been or wouldn’t be quiet about racism any longer.

She starts this collection of stories with Ella Josephine Baker, whose parents and grandparents modeled activism and who, because of her own student activism, would be “crowned the mother of the Civil Rights Movement.” Baker, in fact, was the woman who formed the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, or SNCC, in 1960.

Nine teenagers, known as the Scottsboro Nine were wrongly arrested for raping two white women in 1931 and were all released, thanks to the determination of white lawyer-allies who were affiliated with the International Labor Defense and the outrage of students on campuses around America.

Students refused to let a “Gentleman’s Agreement” pass when it came to sports and equality in 1940. Barbara Johns demanded equal education under the law in Virginia in 1951. Huey Newton and Bobby Seale formed the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense in 1966. And after Trayvon Martin (2012) and George Floyd (2020) were killed, students used the internet as a new form of fighting for justice.

No doubt, by now, you’ve read a lot of books about activism. There are many of them out there, and they’re pretty hard to miss. With that in mind, there are reasons not to miss “Resist!”

You’ll find the main one by looking between the lines and in each chapter’s opening.

There, Omokha weaves her personal story in with that of activists at different times through the decades, matching her experiences with history and making the whole timeline even more relevant.

In doing so, the point of view she offers – that of a woman who wasn’t totally raised in an atmosphere filled with racism, who wasn’t immersed in it her whole life – lets these historical accounts land with more impact.

This book is for people who love history or a good, short biography, but it’s also excellent reading for anyone who sees a need for protest or action and questions the status quo. If that’s the case, then “Resist!” may be the answer.

“Resist! How a Century of Young Black Activists Shaped America” by Rita Omokha, c.2024, St. Martin’s Press. $29.00

Black History

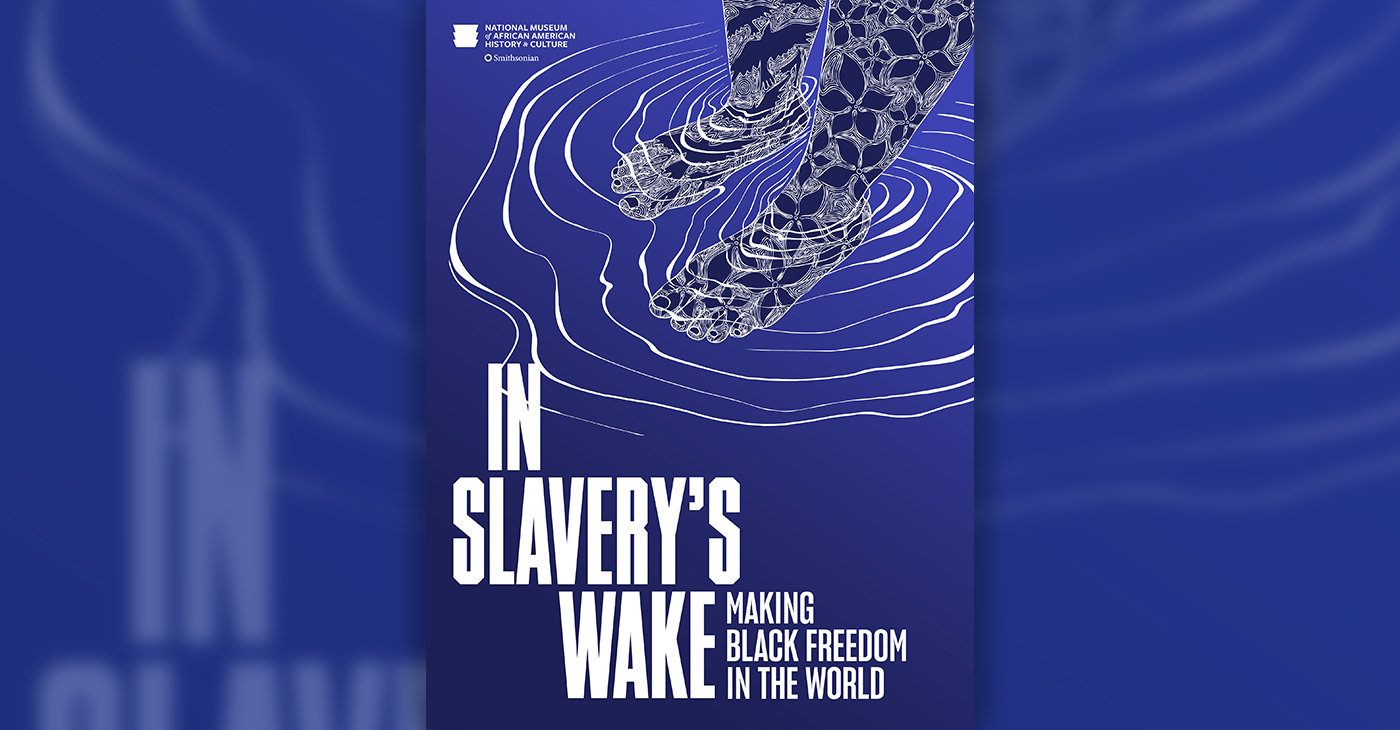

Book Review: In Slavery’s Wake: Making Black Freedom in the World

It’s a tale of heroes: the Maroons, who created communities in unwanted swampland, and welcomed escaped slaves into their midst; Sarah Baartman, the “Hottentot Venus”; Marème Diarra, who walked more than 2000 miles from Sudan to Senegal with her children to escape slavery; enslaved farmers and horticulturists; and everyday people who still talk about slavery and what the institution left behind.

By Terri Schlichenmeyer

Ever since you learned how it happened you couldn’t get it out of your mind.

People, packed like pencils in a box, tightly next to each other, one by one by one, tier after tier. They couldn’t sit up, couldn’t roll over or scratch an itch or keep themselves clean on a ship that took them from one terrible thing to another. And in the new book “In Slavery’s Wake,” essays by various contributors, you’ll see what trailed in waves behind those vessels.

You don’t need to be told about the horrors of slavery. You’ve grown up knowing about it, reading about it, thinking about everything that’s happened because of it in the past four hundred years. And so have others: in 2014, a committee made of “key staff from several world museums” gathered to discuss “telling the story of racial slavery and colonialism as a world system…” so that together, they could implement a “ten-year road map to expand… our practices of truth telling…”

Here, the effects of slavery are compared to the waves left by a moving ship, a wake the story of which some have tried over time to diminish.

It’s a tale filled with irony. Says one contributor, early American Colonists held enslaved people but believed that King George had “unjustly enslaved” the colonists.

It’s the story of a British company that crafted shackles and cuffs and that still sells handcuffs “used worldwide by police and militaries” today.

It’s a tale of heroes: the Maroons, who created communities in unwanted swampland, and welcomed escaped slaves into their midst; Sarah Baartman, the “Hottentot Venus”; Marème Diarra, who walked more than 2000 miles from Sudan to Senegal with her children to escape slavery; enslaved farmers and horticulturists; and everyday people who still talk about slavery and what the institution left behind.

Today, discussions about cooperation and diversity remain essential.

Says one essayist, “… embracing a view of history with a more expansive definition of archives in all their forms must be fostered in all societies.”

Unless you’ve been completely unaware and haven’t been paying attention for the past 150 years, a great deal of what you’ll read inside “In Slavery’s Wake” is information you already knew and images you’ve already seen.

Look again, though, because this comprehensive book isn’t just about America and its history. It’s about slavery, worldwide, yesterday and today.

Casual readers – non-historians especially – will, in fact, be surprised to learn, then, about slavery on other continents, how Africans left their legacies in places far from home, and how the “wake” they left changed the worlds of agriculture, music, and culture. Tales of individual people round out the narrative, in legends that melt into the stories of others and present new heroes, activists, resisters, allies, and tales that are inspirational and thrilling.

This book is sometimes a difficult read and is probably best consumed in small bites that can be considered with great care to appreciate fully. Start “In Slavery’s Wake,” though, and you won’t be able to get it out of your mind.

Edited by Paul Gardullo, Johanna Obenda, and Anthony Bogues, Author: Various Contributors, c.2024, Smithsonian Books, $39.95

Arts and Culture

In ‘Affrilachia: Testimonies,’ Puts Blacks in Appalacia on the Map

By Terri Schlichenmeyer

The Bookworm Sez

An average oak tree is bigger around than two people together can reach.

That mighty tree starts out with an acorn the size of a nickel, ultimately growing to some 80 feet tall, with a canopy of a hundred feet or more across.

And like the new book, “Affrilachia” by Chris Aluka Berry (with Kelly Elaine Navies and Maia A. Surdam), its roots spread wide and wider.

Affriclachia is a term a Kentucky poet coined in the 1990s referring to the Black communities in Appalachia who are similarly referred to as Affrilachians.

In 2016, “on a foggy Sunday morning in March,” Berry visited Affrilachia for the first time by going the Mount Zion AME Zion Church in Cullowhee, North Carolina. The congregation was tiny; just a handful of people were there that day, but a pair of siblings stood out to him.

According to Berry, Ann Rogers and Mae Louise Allen lived on opposite sides of town, and neither had a driver’s license. He surmised that church was the only time the elderly sisters were together then, but their devotion to one another was clear.

As the service ended, he asked Allen if he could visit her. Was she willing to talk about her life in the Appalachians, her parents, her town?

She was, and arrangements were made, but before Barry could get back to Cullowhee, he learned that Allen had died. Saddened, he wondered how many stories are lost each day in mountain communities where African Americans have lived for more than a century.

“I couldn’t make photographs of the past,” he says, “but I could document the people and places living now.”

In doing so he also offers photographs that he collected from people he met in ‘Affrilachia,’ in North Carolina, Georgia, Kentucky, and Tennessee, at a rustic “camp” that was likely created by enslaved people, at churches, and in modest houses along highways.

The people he interviewed recalled family tales and community stories of support, hardship, and home.

Says coauthor Navies, “These images shout without making a sound.”

If it’s true what they say about a picture being worth 1,000 words, then “Affrilachia,” as packed with photos as it is, is worth a million.

With that in mind, there’s not a lot of narrative inside this book, just a few poems, a small number of very brief interviews, a handful of memories passed down, and some background stories from author Berry and his co-authors. The tales are interesting but scant.

For most readers, though, that lack of narrative isn’t going to matter much. The photographs are the reason why you’d have this book.

Here are pictures of life as it was 50 years or a century ago: group photos, pictures taken of proud moments, worn pews, and happy children. Some of the modern pictures may make you wonder why they’re included, but they set a tone and tell a tale.

This is the kind of book you’ll take off the shelf, and notice something different every time you do. “Affrilachia” doesn’t contain a lot of words, but it’s a good choice when it’s time to branch out in your reading.

“Affrilachia: Testimonies,” by Chris Aluka Berry with Kelly Elaine Navies and Maia A. Surdam

c.2024, University of Kentucky Press, $50.00.

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoBooks for Ghana

-

Arts and Culture4 weeks ago

Arts and Culture4 weeks agoPromise Marks Performs Songs of Etta James in One-Woman Show, “A Sunday Kind of Love” at the Black Repertory Theater in Berkeley

-

Bay Area3 weeks ago

Bay Area3 weeks agoGlydways Breaking Ground on 14-Acre Demonstration Facility at Hilltop Mall

-

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks ago‘Donald Trump Is Not a God:’ Rep. Bennie Thompson Blasts Trump’s Call to Jail Him

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoLiving His Legacy: The Late Oscar Wright’s “Village” Vows to Inherit Activist’s Commitment to Education

-

Arts and Culture3 weeks ago

Arts and Culture3 weeks agoIn ‘Affrilachia: Testimonies,’ Puts Blacks in Appalacia on the Map

-

Alameda County3 weeks ago

Alameda County3 weeks agoAC Transit Holiday Bus Offering Free Rides Since 1963

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoCalifornia, Districts Try to Recruit and Retain Black Teachers; Advocates Say More Should Be Done