Book Reviews

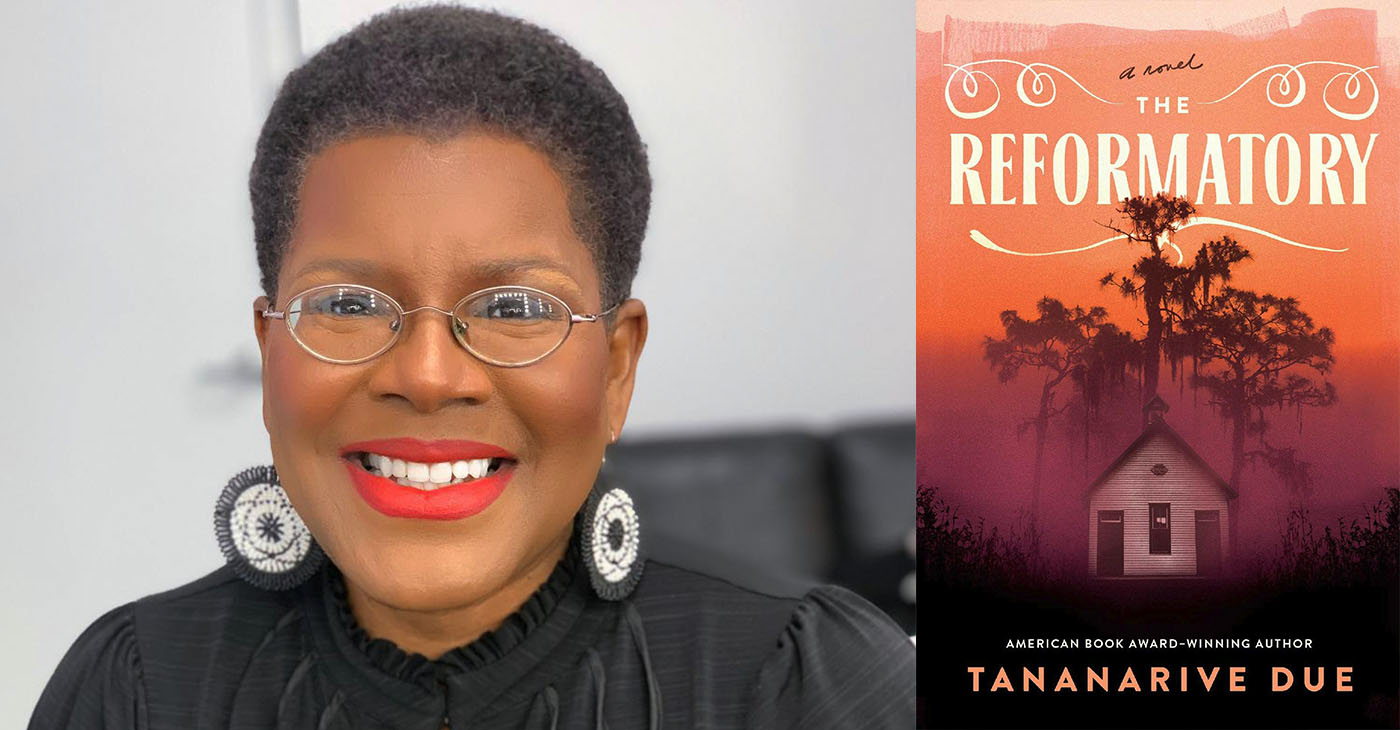

Real Life Fears During Jim Crow Era Compound Horror for Incarcerated Children in ‘The Reformatory’

You’ll do better next time. You’re sorry, deeply sorry, sincere in your apology, and it won’t happen again. You had a chance to think about your transgressions and you were wrong. What can you do or say to make things better? How can you properly make amends? As in the new book “The Reformatory” by Tananarive Due, how long should you pay for something you didn’t do?

By Terri Schlichenmeyer

The Bookworm Sez

You’ll do better next time.

You’re sorry, deeply sorry, sincere in your apology, and it won’t happen again. You had a chance to think about your transgressions and you were wrong. What can you do or say to make things better? How can you properly make amends?

As in the new book “The Reformatory” by Tananarive Due, how long should you pay for something you didn’t do?

The north Florida countryside was passing by fast as Robert Stephens sat small in the passenger seat of the fancy car. Any other time, he’d be enjoying himself but not now. No, this time, he was on his way to The Reformatory, a school for boys who’d broken the law.

How did things get this far, this fast? It wasn’t but a day or so before that Robert and his sister Gloria were walking down the road when Lyle McCormack, son of Gracetown’s richest man, tried to kiss Gloria and Robert kicked Lyle, in defense of his sister.

It was 1950 and every Black person knew that you didn’t do that to somebody who was white, but Robert kicked before he could stop himself and he was arrested. And here he was, 12 years old, on his way to a place where Papa said was where the killing started.

But Papa wasn’t around anymore, having been run out of town for his union work. It was just Gloria, Robert, and old Miz Lottie, and Robert was terrified.

Ever since he was little, he’d been able to see things nobody else could see. He told Gloria that Mama visited him sometimes, even though she’d been dead for months. He knew things, too; the closer the car got to The Reformatory, the more he knew he couldn’t stay there for the next six months. The place smelled like smoke, but there were no fires.

It smelled like death and fear.

He had to trust that Gloria would get him home. He’d trust Mama to watch over him.

He could see “haints” at The Reformatory. The place was full of them…

Though it might seem like one, “The Reformatory” is not just a ghost story. It’s tighter, scarier, more ominous because this tale has deep roots based in truth.

Like the tentacles belonging to some sort of evil creature, Jim Crow laws ooze into every corner of this book, wrapping tendrils around the characters and their lives. That’s a terror that’s told authentically and is (un)easy to imagine, but then author Tananarive Due kicks the frights into maximum overdrive with ghosts and madmen that you can sometimes barely tell apart.

Even scarier: they’re inside The Reformatory, and outside it, and they want revenge — both of the otherworldly kind and based in reality. Scarier still: they’re willing to make deals.

If you have a heart condition, you might want to pass on this book because it’ll raise your pulse rate to the roof. If you’re healthy and brave, though, look for “The Reformatory.” When it comes to scary novels, you’ll never do better.

“The Reformatory” by Tananarive Due, c.2023, Gallery/Saga Press, $28.99, 576 pages

Activism

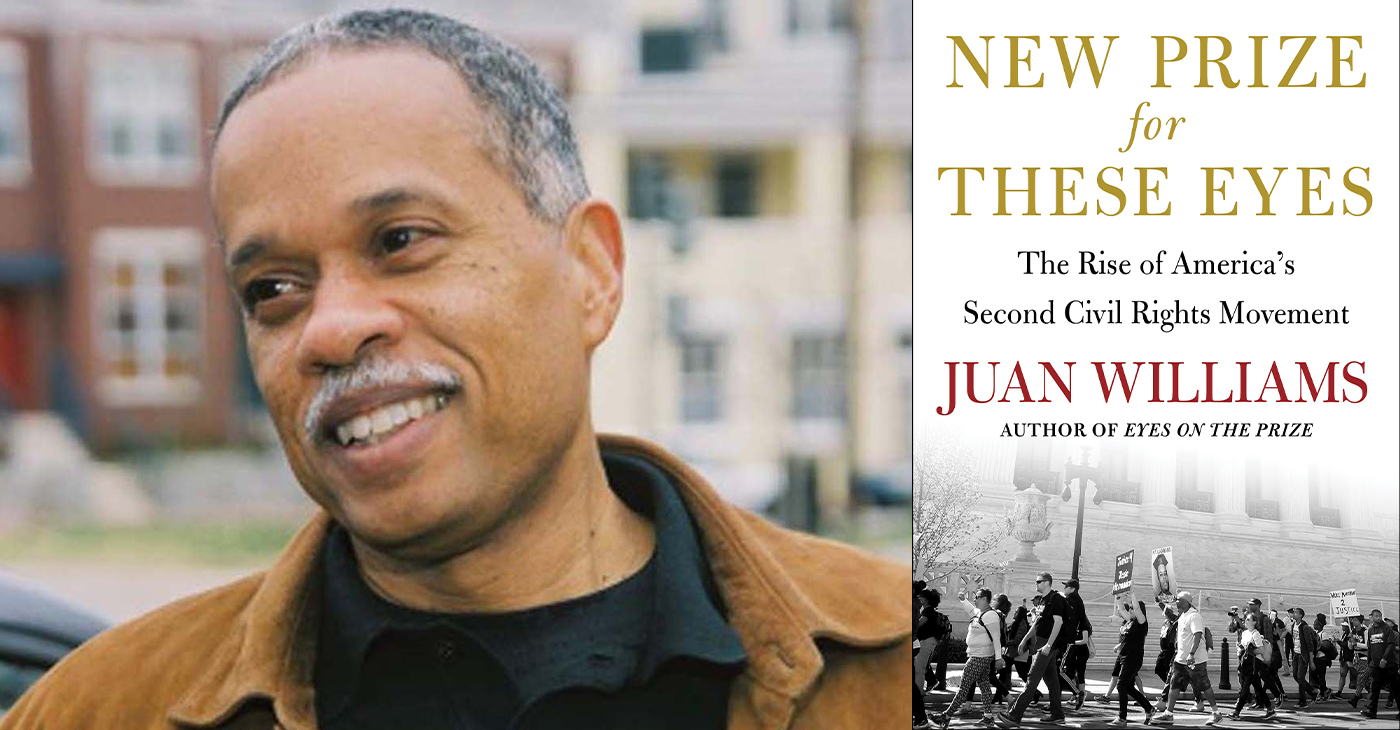

Book Review: Author Juan Williams Makes Case for Second Civil Rights Movement in ‘New Eyes for This Prize’

History disagrees on the exact catalyst for the Civil Rights Movement. However, Williams says that “the second Civil Rights Movement” sparked at the 2004 Democratic National Convention, and it took less than 20 minutes.

By Terri Schlichenmeyer

The Bookworm Sez

You’re not letting go that easily.

No, you’re on the right side of justice and you’re not letting go of the issue. Your heels are dug in, your back is straight, and your resolve is steely. You have a plan, and you’ll keep it, and see it to the end no matter what happens. As in the new book “New Prize for These Eyes” by Juan Williams, there are some who’ve gone before you, but your effort is what matters now.

History disagrees on the exact catalyst for the Civil Rights Movement. However, Williams says that “the second Civil Rights Movement” sparked at the 2004 Democratic National Convention, and it took less than 20 minutes.

Not long after young Senator Barack Obama, whose presence was meant to attract Black voters, began his speech at that convention, he had the audience cheering. He was positive, energetic, and energizing, and spoke of “a new sense of common purpose,” which spurred a Second Civil Rights Movement and a mandate to “deal with … cultural issues that the first Movement had left unresolved …”

The speech thrust Obama onto the national stage and, with the endorsement of many old guard Civil Rights Movement figures, ultimately put him in the White House. His presence there wasn’t without issues, both politically and racially, however: the deaths of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, and Philando Castile, and others, absolutely affected Obama’s terms, in part because “he acted only as a referee” and didn’t “take any special level of response as a Black man.” Still, early civil rights leaders agreed with him that America was “better” than it was 60 years ago.

Before Obama’s second term was over, a “right-wing backlash” that was “fueled by grievance” ushered Donald Trump into office but by then, young Black Americans had flocked to social media and gave root to the Black Lives Matter movement. “COVID-19 would also transform” the situation.

By the summer of 2024, “the Second Civil Rights Movement was far from completing its agenda,” says Williams, but “it had still achieved remarkable success.”

Pay very close attention while you’re reading this book. It’s filled with politics, but there’s a pay-off in it: Williams does a little forecasting toward the end of “New Prize for These Eyes,” promising readers a new movement, a third one, to come.

Even if you’re not particularly a politics-watcher, Williams draws your attention to the last 20 years and how they keenly shaped racism and racial issues in America. Sometimes, he seems to invite argument, using Obama as a singular catalyst for this “second” movement and its current continuation, fairly or unfairly.

He also credits other people and events that will make readers want to find someone to discuss his theories with. The tantalizing idea of a third movement will only underscore that desire.

As a sequel to Williams’ “Eyes on the Prize,” this is a must-read for anyone who knows where we’ve been or wonders where we’re going. Find “New Prize for These Eyes.”

You will not want to let it go.

“New Prize for These Eyes: The Rise of America’s Second Civil Rights Movement,” Author: Juan Williams c.2025, Simon & Schuster, $28.99.

Arts and Culture

BOOK REVIEW: On Love

King entered college at age fifteen and after graduation, he was named associate pastor at his father’s church. At age twenty-five, he became the pastor at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Ala. In late 1956, he was apprehended for his part in the bus boycott there, his first of many arrests for non-violent protests and activism for Civil Rights. But when asked if those things were what he hoped he’d be honored for in years to come, King said he wanted to be remembered as “’someone who tried to love somebody.’”

By Terri Schlichenmeyer

Author: Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., c.2024, Harper Collins, Martin Luther King Jr. Library, $18.99

Turn the volume up, please.

You need it louder because this is something you’ve been waiting to hear. You need to listen very closely; these words mean a great deal to you, and they might change your life. As in the new book, “On Love” by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., the message beneath the message is the most important.

As the grandson and great-grandson of pastors and the son of the senior pastor at Ebeneezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, it may seem as though young Martin Luther King, Jr., born in 1929, already had his life set.

King entered college at age fifteen and after graduation, he was named associate pastor at his father’s church. At age twenty-five, he became the pastor at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Ala. In late 1956, he was apprehended for his part in the bus boycott there, his first of many arrests for non-violent protests and activism for Civil Rights.

But when asked if those things were what he hoped he’d be honored for in years to come, King said he wanted to be remembered as “’someone who tried to love somebody.’”

His words, essays, letters, and speeches reflect that desire.

In a 1955 sermon in Montgomery, he used a parable to explain why White people needed love to gain compassion. In 1956, he wrote about the bombing of his home, telling his readers that no retaliation was needed, that to “confront the problem with love” was the righteous and better thing to do.

Later that year, he said, “I want you to love our enemies… Love them and let them know you love them.” And in November, 1956, he said, “If you have not love, it means nothing.”

“Love is the greatest force in all the world,” he said in 1962.

He wrote a book on the subject, Strength to Love, in 1963.

In 1967, just months before his assassination, he said that “power at its best is love.”

When we talk about Dr. King’s life and his legacy, so much focus is put on his work on behalf of Civil Rights and equality that it’s easy to lose sight of the thing which he felt was more important. In “On Love,” any omission is rectified nicely.

This book, “excerpted to highlight the material where King specifically addressed the topic of love,” is full of pleasant surprises, words with impact, and thought provokers. King’s speeches hammered home a need to love one’s enemies, woven into messages of gentle resistance and strength. He explained the different “levels” of love in a way that makes sense when related to equality and justice. The bits and pieces collected here will linger in reader’s minds, poking and prodding and reminding.

If your shelves are full of books about Dr. King, know that this is a unique one, and it’s perfect for our times, now. Don’t race through it; instead, savor what you’ll read and keep it close. “On Love” is a book you’ll want to turn to, often.

Activism

‘Resist’ a Look at Black Activism in U.S. Through the Eyes of a Native Nigerian

In 1995, after she and her brothers traveled from their native Nigeria to join their mother at her new home in the South Bronx, young Omokha’s eyes were opened. She quickly understood that the color of her skin – which was “synonymous with endless striving and a pursuit of excellence” in Nigeria – was “so problematic in America.”

By Terri Schlichenmeyer, The Bookworm Sez

Throughout history, when decisions were needed, the answer has often been “no.”

‘No,’ certain people don’t get the same education as others. ‘No,’ there is no such thing as equality. ‘No,’ voting can be denied and ‘no,’ the laws are different, depending on the color of one’s skin. And in the new book, “Resist!” by Rita Omokha, ‘no,’ there is not an obedient acceptance of those things.

In 1995, after she and her brothers traveled from their native Nigeria to join their mother at her new home in the South Bronx, young Omokha’s eyes were opened. She quickly understood that the color of her skin – which was “synonymous with endless striving and a pursuit of excellence” in Nigeria – was “so problematic in America.”

That became a bigger matter to Omokha later, 15 years after her brother was deported: she “saw” him in George Floyd, and it shook her. Troubled, she traveled to America on a “pilgrimage for understanding [her] Blackness…” She began to think about the “Black young people across America” who hadn’t been or wouldn’t be quiet about racism any longer.

She starts this collection of stories with Ella Josephine Baker, whose parents and grandparents modeled activism and who, because of her own student activism, would be “crowned the mother of the Civil Rights Movement.” Baker, in fact, was the woman who formed the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, or SNCC, in 1960.

Nine teenagers, known as the Scottsboro Nine were wrongly arrested for raping two white women in 1931 and were all released, thanks to the determination of white lawyer-allies who were affiliated with the International Labor Defense and the outrage of students on campuses around America.

Students refused to let a “Gentleman’s Agreement” pass when it came to sports and equality in 1940. Barbara Johns demanded equal education under the law in Virginia in 1951. Huey Newton and Bobby Seale formed the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense in 1966. And after Trayvon Martin (2012) and George Floyd (2020) were killed, students used the internet as a new form of fighting for justice.

No doubt, by now, you’ve read a lot of books about activism. There are many of them out there, and they’re pretty hard to miss. With that in mind, there are reasons not to miss “Resist!”

You’ll find the main one by looking between the lines and in each chapter’s opening.

There, Omokha weaves her personal story in with that of activists at different times through the decades, matching her experiences with history and making the whole timeline even more relevant.

In doing so, the point of view she offers – that of a woman who wasn’t totally raised in an atmosphere filled with racism, who wasn’t immersed in it her whole life – lets these historical accounts land with more impact.

This book is for people who love history or a good, short biography, but it’s also excellent reading for anyone who sees a need for protest or action and questions the status quo. If that’s the case, then “Resist!” may be the answer.

“Resist! How a Century of Young Black Activists Shaped America” by Rita Omokha, c.2024, St. Martin’s Press. $29.00

-

#NNPA BlackPress2 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress2 weeks agoTarget Takes a Hit: $12.4 Billion Wiped Out as Boycotts Grow

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoU.S. House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries and Rep. Lateefah Simon to Speak at Elihu Harris Lecture Series

-

Alameda County3 weeks ago

Alameda County3 weeks agoAfter Years of Working Remotely, Oakland Requires All City Employees to Return to Office by April 7

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoActor, Philanthropist Blair Underwood Visits Bay Area, Kicks Off Literacy Program in ‘New Oakland’ Initiative

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoLawsuit Accuses UC Schools of Giving Preference to Black and Hispanic Students

-

Alameda County3 weeks ago

Alameda County3 weeks agoLee Releases Strong Statement on Integrity and Ethics in Government

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoRetired Bay Area Journalist Finds Success in Paris with Black History Tours

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoTwo New California Bills Are Aiming to Lower Your Prescription Drug Costs