Arts and Culture

Bay Area African American Women in Music: ‘Music is in The Ear of The Beholder,’ Says Faye Carol

Veteran Bay Area vocalist Faye Carol doesn’t like being tagged a “jazz singer” or “blues singer,” although she sings both.

“Music is in the ear of the beholder,” says the longtime Berkeley resident. “Those are nice words for boxes for selling. If somebody’s gonna come and buy something, they gotta compartmentalize you. I just don’t believe in boxing myself in.”

Carol says, “I’ve been blessed to be able to sing what I like. My biggest hero for that was Ray Charles. You could not pigeonhole that man. He brought his Rayness to whatever he did.”

Carol was born in Meridian, Mississippi, and spent her first 10 years there with her grandmother, a schoolteacher. Except for summers, when she travelled to Port Chicago, California, to be with her parents who moved there for work.

Carol says living in Mississippi was “absolutely wonderful,” yet she was well aware of the “white only” signs and other forms of racism that surrounded her.

“The great thing about segregation was that you were just with your own people,” she says.

“The other thing about segregation that wasn’t so great, but still had side benefits was that you had to be pretty self-sufficient ‘cause wasn’t nobody gonna come and do too much of nothin’ for you. We had our own newspaper, our own restaurants, our own undertakers, our own hairdressers and those juke joints on the outskirts of town,” says Carol.

“We never did try to go into [white] restaurants,” she adds. “Our food was better, anyway.”

Carol began singing in church as a teenager in Pittsburg – where her family had relocated from Port Chicago – and joined a gospel group called the Angelaires, led by pianist-songwriter Faidest Wagoner and also included future singing star Leola Jiles. They performed at churches throughout Northern California and did a national tour, including stops in Chicago, Detroit and New York City.

After winning a talent contest at the Oakland Auditorium during the mid-‘60s, Carol landed a gig with R&B guitarist Johnny Talbot and De Thangs at the Zanzibar Room in the California Hotel.

Carol has, for many years, imparted her vast knowledge of African American music to children, teenagers and adults through workshops and private lessons.

Her late husband, Jim Gamble, a jazz guitar player and bassist who taught Black music history at U.C. Berkeley, helped broaden her musical horizons beyond the R&B hits of the day. She in turn began schooling their daughter Kito, then a budding young piano player, in the music of blues pianist Otis Spann and such jazzmen as McCoy Tyner and Cecil Taylor.

Kito went on to work as her mother’s piano accompanist for more than a decade before launching her own career as a Christian rapper, known as Sista Kee.

On Sunday, May 10 at 5 p.m., Carol will perform with her quartet and some of her students at the EastSide Cultural Center, 2277 International Blvd. in Oakland. For more information, call (510) 533-6629.

Veteran Bay Area vocalist Faye Carol doesn’t like being tagged a “jazz singer” or “blues singer,” although she sings both.

“Music is in the ear of the beholder,” says the longtime Berkeley resident. “Those are nice words for boxes for selling. If somebody’s gonna come and buy something, they gotta compartmentalize you. I just don’t believe in boxing myself in.”

Carol says, “I’ve been blessed to be able to sing what I like. My biggest hero for that was Ray Charles. You could not pigeonhole that man. He brought his Rayness to whatever he did.”

Carol was born in Meridian, Mississippi, and spent her first 10 years there with her grandmother, a schoolteacher. Except for summers, when she travelled to Port Chicago, California, to be with her parents who moved there for work.

Carol says living in Mississippi was “absolutely wonderful,” yet she was well aware of the “white only” signs and other forms of racism that surrounded her.

“The great thing about segregation was that you were just with your own people,” she says.

“The other thing about segregation that wasn’t so great, but still had side benefits was that you had to be pretty self-sufficient ‘cause wasn’t nobody gonna come and do too much of nothin’ for you. We had our own newspaper, our own restaurants, our own undertakers, our own hairdressers and those juke joints on the outskirts of town,” says Carol.

“We never did try to go into [white] restaurants,” she adds. “Our food was better, anyway.”

Carol began singing in church as a teenager in Pittsburg – where her family had relocated from Port Chicago – and joined a gospel group called the Angelaires, led by pianist-songwriter Faidest Wagoner and also included future singing star Leola Jiles. They performed at churches throughout Northern California and did a national tour, including stops in Chicago, Detroit and New York City.

After winning a talent contest at the Oakland Auditorium during the mid-‘60s, Carol landed a gig with R&B guitarist Johnny Talbot and De Thangs at the Zanzibar Room in the California Hotel.

Carol has, for many years, imparted her vast knowledge of African American music to children, teenagers and adults through workshops and private lessons.

Her late husband, Jim Gamble, a jazz guitar player and bassist who taught Black music history at U.C. Berkeley, helped broaden her musical horizons beyond the R&B hits of the day. She in turn began schooling their daughter Kito, then a budding young piano player, in the music of blues pianist Otis Spann and such jazzmen as McCoy Tyner and Cecil Taylor.

Kito went on to work as her mother’s piano accompanist for more than a decade before launching her own career as a Christian rapper, known as Sista Kee.

On Sunday, May 10 at 5 p.m., Carol will perform with her quartet and some of her students at the EastSide Cultural Center, 2277 International Blvd. in Oakland. For more information, call (510) 533-6629.

Activism

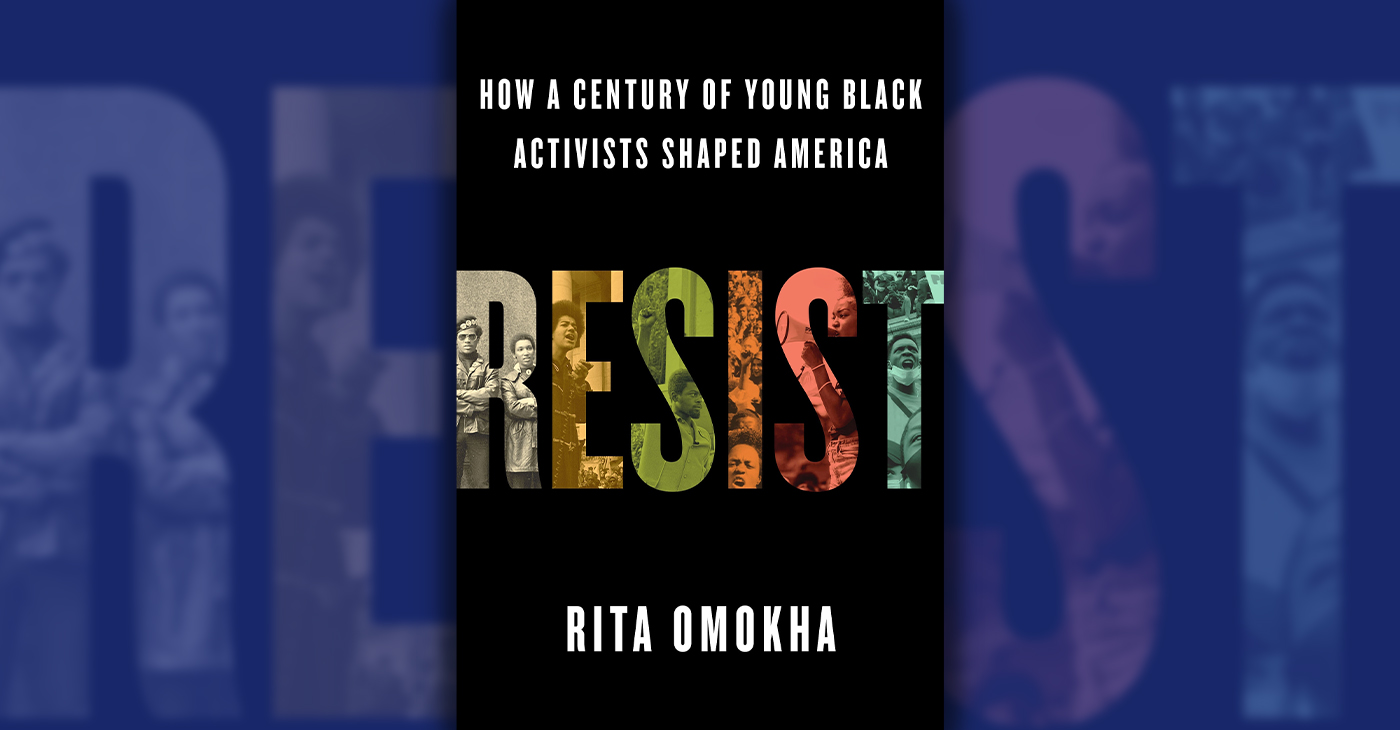

‘Resist’ a Look at Black Activism in U.S. Through the Eyes of a Native Nigerian

In 1995, after she and her brothers traveled from their native Nigeria to join their mother at her new home in the South Bronx, young Omokha’s eyes were opened. She quickly understood that the color of her skin – which was “synonymous with endless striving and a pursuit of excellence” in Nigeria – was “so problematic in America.”

By Terri Schlichenmeyer, The Bookworm Sez

Throughout history, when decisions were needed, the answer has often been “no.”

‘No,’ certain people don’t get the same education as others. ‘No,’ there is no such thing as equality. ‘No,’ voting can be denied and ‘no,’ the laws are different, depending on the color of one’s skin. And in the new book, “Resist!” by Rita Omokha, ‘no,’ there is not an obedient acceptance of those things.

In 1995, after she and her brothers traveled from their native Nigeria to join their mother at her new home in the South Bronx, young Omokha’s eyes were opened. She quickly understood that the color of her skin – which was “synonymous with endless striving and a pursuit of excellence” in Nigeria – was “so problematic in America.”

That became a bigger matter to Omokha later, 15 years after her brother was deported: she “saw” him in George Floyd, and it shook her. Troubled, she traveled to America on a “pilgrimage for understanding [her] Blackness…” She began to think about the “Black young people across America” who hadn’t been or wouldn’t be quiet about racism any longer.

She starts this collection of stories with Ella Josephine Baker, whose parents and grandparents modeled activism and who, because of her own student activism, would be “crowned the mother of the Civil Rights Movement.” Baker, in fact, was the woman who formed the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, or SNCC, in 1960.

Nine teenagers, known as the Scottsboro Nine were wrongly arrested for raping two white women in 1931 and were all released, thanks to the determination of white lawyer-allies who were affiliated with the International Labor Defense and the outrage of students on campuses around America.

Students refused to let a “Gentleman’s Agreement” pass when it came to sports and equality in 1940. Barbara Johns demanded equal education under the law in Virginia in 1951. Huey Newton and Bobby Seale formed the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense in 1966. And after Trayvon Martin (2012) and George Floyd (2020) were killed, students used the internet as a new form of fighting for justice.

No doubt, by now, you’ve read a lot of books about activism. There are many of them out there, and they’re pretty hard to miss. With that in mind, there are reasons not to miss “Resist!”

You’ll find the main one by looking between the lines and in each chapter’s opening.

There, Omokha weaves her personal story in with that of activists at different times through the decades, matching her experiences with history and making the whole timeline even more relevant.

In doing so, the point of view she offers – that of a woman who wasn’t totally raised in an atmosphere filled with racism, who wasn’t immersed in it her whole life – lets these historical accounts land with more impact.

This book is for people who love history or a good, short biography, but it’s also excellent reading for anyone who sees a need for protest or action and questions the status quo. If that’s the case, then “Resist!” may be the answer.

“Resist! How a Century of Young Black Activists Shaped America” by Rita Omokha, c.2024, St. Martin’s Press. $29.00

Activism

Oakland Community Art Center is Helping Immigrants Heal from Trauma

The programs are catered to youth and adults with programs called “Arts in Schools” and “Arts and Wellness.” Students are encouraged to participate in music, crafts, and dancing. In contrast, adults can join support groups to connect with others and receive mental health resources to alleviate trauma they may have previously experienced.

By Magaly Muñoz

A local community art center ARTogether is creating a safe place for immigrants and refugees one craft at a time.

After Donald Trump’s first presidential term started in 2017, Leva Zand saw firsthand the impact of discrimination towards immigrants. She wanted to give this community a space to heal through a creative outlet, which prompted her to start ARTogether.

“Folks can come together and do art activities, celebrate their culture, and basically be in a judgmental free environment, no matter what is their immigration status or how well they speak English, when they came to this country, what generation they are,” Zand explained. “The idea was how to use arts and culture for community building and connection between refugees, immigrants themselves and with the broader community.”

Located in downtown Oakland, the space is dedicated partly for galleries and art shows featuring local immigrant artists. The remaining area is a communal studio where ARTogether hosts its regular activities.

Art is used as a therapeutic medium that allows participants to process and express their emotions and experiences and build community with others in the studio, Zand said.

The programs are catered to youth and adults with programs called “Arts in Schools” and “Arts and Wellness.” Students are encouraged to participate in music, crafts, and dancing. In contrast, adults can join support groups to connect with others and receive mental health resources to alleviate trauma they may have previously experienced.

Zand told the Post that a lot of the issues participants come into the program with are related to feeling a lack of support or community after newly arriving to the area from their home countries. While many come from areas where traditional therapy is considered taboo, art lets people of all backgrounds express themselves in a creative form that makes sense to them.

The center can also provide referrals and direct contacts to traditional mental and physical health professionals and legal and social programs for those who need more extensive assistance.

Because of how the organization started, ARTogether has a strong ‘Stop the Hate’ messaging built into its mission. They began promoting the advocacy for anti-immigrant and anti-refugee hate before it was officially established across several demographics during the pandemic, Zand said.

“We really want to activate this space for the community to get together, to share, to strategize, to see how they can advocate at the local, state and even national level for their rights,” Zand shared.

Anticipating an influx in stress and trauma for residents after the presidential inauguration in January, ARTogether is hosting a community gathering at the end of the month in order to give people the space to express their feelings through crafts.

These gatherings, or “Gather In’s”, will be held monthly, or for as long as funding can sustain them, which Zand said might not be for long.

The organization recently lost one of its grants from the city of Oakland during the major budget cuts earlier this month that slashed funding for arts and culture programs. They were meant to receive a $20,000 grant through the city’s initial contingency budget plan but the money is now gone until Oakland can get their revenue up again.

Zand shared she worries about the state of the country come the new year and where her organization may end up as well if budget restraints continue at the local and state level.

“We are really facing uncertainty. We don’t know what is happening…We don’t know how bad it’s going to be,” she said.

This resource was supported in whole or in part by funding provided by the State of California, administered by the California State Library via California Black Media as part of the Stop theHate program. The program is supported by partnership with the California Department of Social Services and the California Commission on Asian and Pacific Islander American Affairs. To report a hate incident or hate crime and get support, go to https://www.cavshate.org/

#NNPA BlackPress

FILM REVIEW: The Six Triple Eight: Tyler Perry Salutes WWII Black Women Soldiers

NNPA NEWSWIRE — The film features an all-star cast including Susan Sarandon as Eleanor Roosevelt, Sam Waterston as President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Oprah Winfrey as Mary McLeod Bethune and Ebony Obsidian (Sistas, If Beale Street Could Talk)) who shows her acting chops by holding her own playing Lena, a bereaved private, opposite Washington.

By Nsenga K. Burton

NNPA Newswire Culture and Entertainment Editor

The Six Triple Eight tells the important yet often overlooked story of the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion, an all-Black, all-woman unit in World War II. The film chronicles the battalion’s efforts to clear a massive backlog of undelivered mail meant for U.S. troops, a task that was both vital and challenging. In a show-stopping speech atop a mountain of mail, Major Charity Adams, played fiercely by Kerry Washington, explains the importance of mail during wartime and its relationship to soldier morale. Adams, who is continuously denied promotions despite her impeccable professional performance, leads 855 Black women through 17 million pieces of mail in an abandoned, cold and drafty school rife with “vermin” to raise the morale of soldiers and bring closure to families who haven’t heard from loved ones in nearly a year.

The film features an all-star cast, including Susan Sarandon as Eleanor Roosevelt, Sam Waterston as President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Oprah Winfrey as Mary McLeod Bethune, and Ebony Obsidian (Sistas, If Beale Street Could Talk), who shows her acting chops by holding her own playing Lena, a bereaved private, opposite Washington.

Lena is a highly sensitive and intelligent young woman who is distraught over the death of her Jewish “boyfriend,” Abram David (Gregg Sulkin), who is killed in the war. Instead of attending college, Lena enlists in the army to “fight Hitler.” En route to basic training in Georgia, Lena is joined with a group of women in the segregated battalion, all of whom are running away from a traumatic past and running towards a brighter future. What emerges is a strong sisterhood that bonds the women, whether in their barracks or crossing the big pond, which is one of the highlights of the film.

The Six Triple Eight has all of the tropes of a film set during the 1940s, including de facto segregation here and abroad, the mistreatment of Black women in and out of the service by any and everybody, aggressive white men using the N-word with the hard “R,” and older Black women whose hearts are free, but minds are shackled to fear that living in segregation and being subjected to impromptu violence, ridicule, jail or scorn brings to bear.

While the film elevates the untold story of the dynamic, pioneering, and committed Black servicewomen of the Six Triple Eight, the narrative falls prey to Perry’s signature style — heavy-handed dialogue, uneven performances and a redundant script that keeps beating viewers over the head with what many already know as opposed to what we need to know. For example, a short montage of the women working with the mail is usurped by abusive treatment from white, male leaders. A film like this would benefit more from seeing and understanding the dynamism, intelligence and dedication it took for these women to develop and implement a strategy to get this volume of mail to the soldiers and their families.

In another scene, the 6888 soldiers yell out their prior professions, which would prove helpful to keeping their assignment when they come under attack again from the white military men. Visually seeing the Black women demonstrate their talents would be far more satisfying than hearing them ticked off like a grocery list, which undermines the significance of their work and preparation for war as Black women during this harrowing time in history. The lack of emphasis on their skills and capabilities diminishes the overall impact of their story, leaving viewers wanting more depth and insight into their achievements.

While the film highlights the struggles these women faced against institutional racism and sexism, it ultimately falls short in delivering a nuanced portrayal of their significant contributions to the war effort. This is a must-see film because of the subject matter and strong performances by Washington and Obsidian, but the story’s execution makes it difficult to get through.

Tyler Perry is beloved as a filmmaker because he sometimes makes films that people need to see at a particular moment in time (For Colored Girls), resuscitates or helps to keep the careers of super accomplished actors alive (Debi Morgan, Alfre Woodward, Cicely Tyson) and gives young, talented actors like Obsidian, Taylor Polidore Williams (Beauty in Black, Snowfall, All-American HBCU) and Crystal Renee Hayslett (Zatima) a chance to play a lead role when mainstream Hollywood is taking too long. One thing Perry hasn’t done is extend that generosity of spirit to the same extent to the writing and directing categories. Debbie Allen choreographed the march scene for Six Triple Eight. What might this film have been had she directed the film?

This much-anticipated film is a love letter to Black servicewomen and a movie that audiences need to see now that would benefit immensely from stronger writing and direction. Six Triple Eight is a commendable effort to elevate an untold story, but it ultimately leaves viewers craving a more nuanced exploration of the remarkable women at its center.

Six Triple Eight is now playing on Netflix.

This review was written by media critic Nsenga K. Burton, Ph.D., editor-at-large for NNPA/Black Press USA and editor-in-chief of The Burton Wire. Follow her on IG @TheBurtonWire.

-

Activism2 weeks ago

Activism2 weeks agoBooks for Ghana

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoPost News Group to Host Second Town Hall on Racism, Hate Crimes

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoButler, Lee Celebrate Passage of Bill to Honor Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm with Congressional Gold Medal

-

Arts and Culture2 weeks ago

Arts and Culture2 weeks agoPromise Marks Performs Songs of Etta James in One-Woman Show, “A Sunday Kind of Love” at the Black Repertory Theater in Berkeley

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoDelta Sigma Theta Alumnae Chapters Host World AIDS Day Event

-

Activism2 weeks ago

Activism2 weeks ago‘Donald Trump Is Not a God:’ Rep. Bennie Thompson Blasts Trump’s Call to Jail Him

-

Business3 weeks ago

Business3 weeks agoLandlords Are Using AI to Raise Rents — And California Cities Are Leading the Pushback

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of December 11 – 17, 2024