Book Reviews

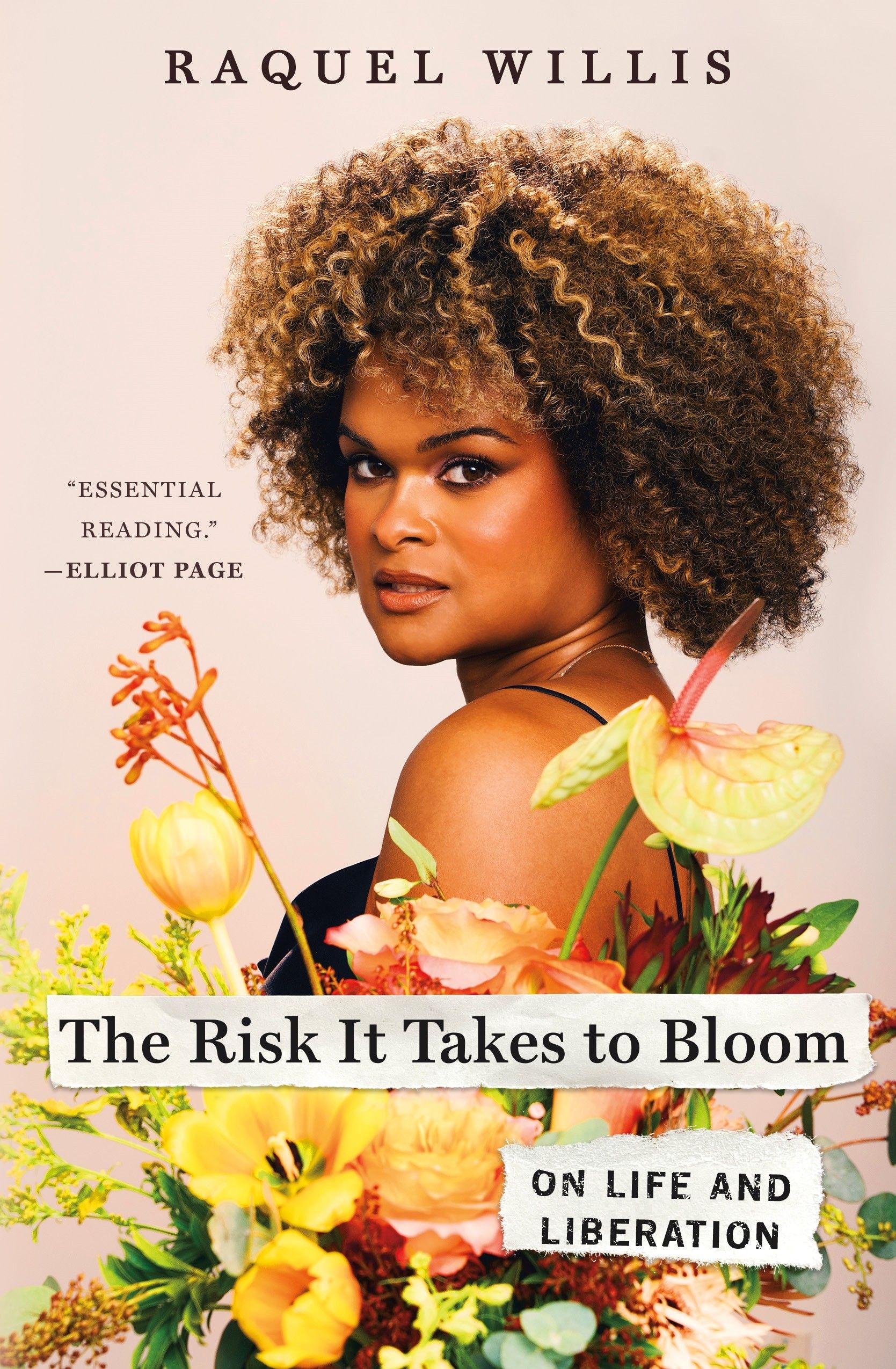

Books: “The Risk It Takes to Bloom: On Life and Liberation” by Raquel Willis

The catalogs should start arriving soon. If you’re a gardener, that’s a siren song for you. What will you put in your pots and plots this spring? What colors will you have, what crops will you harvest? It never gets old: put a seed no bigger than a breadcrumb into some dirt and it becomes dinner in just weeks. All it needs, as in the new memoir “The Risk It Takes to Bloom” by Raquel Willis, is a little time to grow.

Arts and Culture

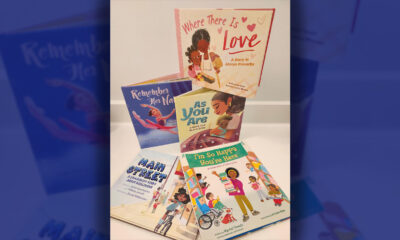

Book Review: Books on Black History and Black Life for Kids

For the youngest reader, “As You Are: A Hope for Black Sons” by Kimberly A. Gordon Biddle, illustrated by David Wilkerson (Magination Press, $18.99) is a book for young Black boys and for their mothers. It’s a hope inside a prayer that the world treats a child gently, and it could make a great baby shower gift.

Advice

BOOK REVIEW: Let Me Be Real With You

At first look, this book might seem like just any other self-help offering. It’s inspirational for casual reader and business reader, both, just like most books in this genre. Dig a little deeper, though, and you’ll spot what makes “Let Me Be Real With You” stand out.

Arts and Culture

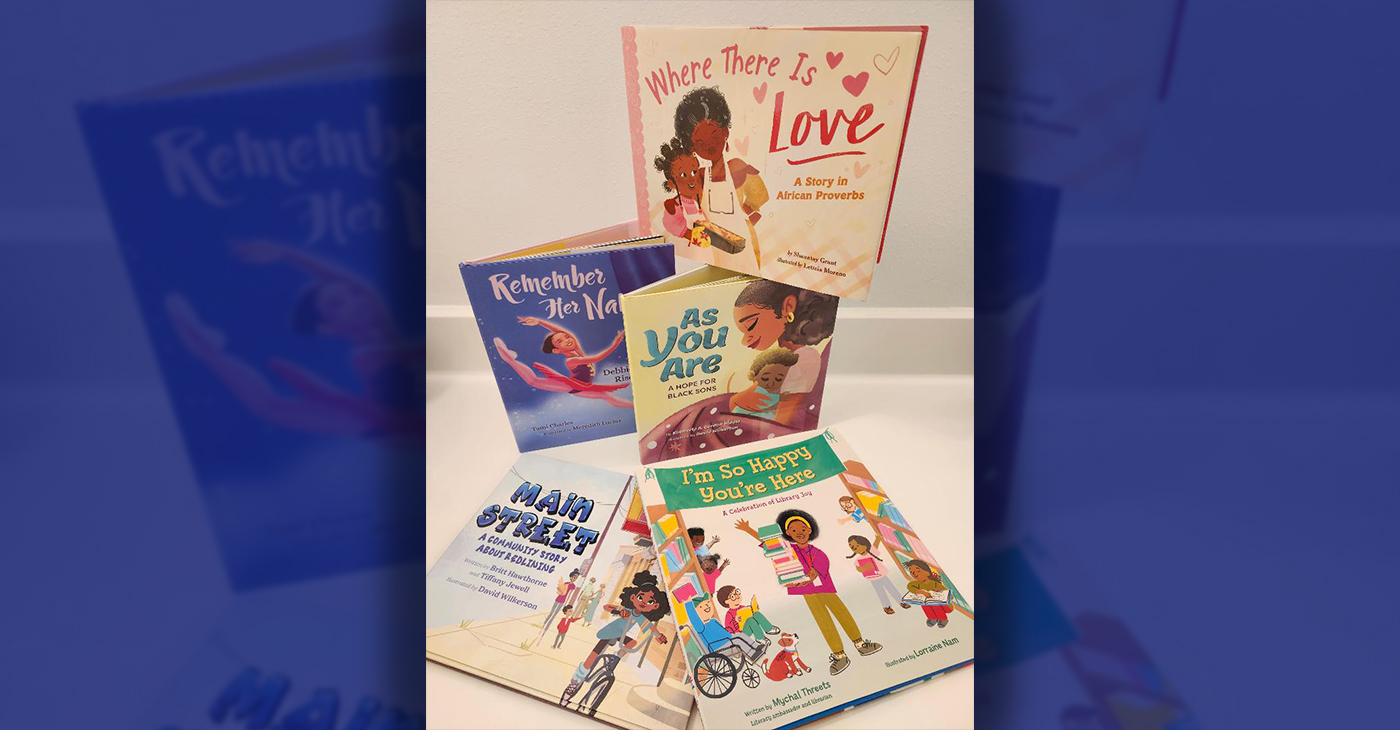

Book Review: American Kings – A Biography of the Quarterback

Wickersham calls his book “a biography,” but it’s just as much a history, since he refers often to the earliest days of the game, as well as the etymology of the word “quarterback.” That helps to lay a solid background, and it adds color to a reader’s knowledge about football itself, while explaining what it takes for men and women to stand out and to achieve gridiron greatness.

-

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks agoDiscrimination in City Contracts

-

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of February 11 – 17, 2026

-

#NNPA BlackPress2 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress2 weeks agoReflecting on Black History Milestones in Birmingham AL

-

Advice4 weeks ago

Advice4 weeks agoRising Optimism Among Small And Middle Market Business Leaders Suggests Growth for California

-

Bay Area3 weeks ago

Bay Area3 weeks agoCITY OF SAN LEANDRO STATE OF CALIFORNIA PUBLIC WORKS DEPARTMENT ENGINEERING DIVISION NOTICE TO BIDDERS FOR ANNUAL STREET OVERLAY/REHABILITATION 2019-21 – PHASE III

-

#NNPA BlackPress2 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress2 weeks agoU.S. manufacturing rebounds – how foundry services are adapting to rising demand

-

#NNPA BlackPress2 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress2 weeks agoPRESS ROOM: NBA Hall of Fame Nominee Terry Cummings Joins 100 Black Men of DeKalb County to Launch Victory & Values Initiative

-

#NNPA BlackPress2 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress2 weeks agoAdvancements in solar technology that are changing the way we power the world