Activism

COMMENTARY: “COVID-19 and White Supremacy, Creating Our New Normal”

We must rescue and refine the best of Black ways. Look at our historical grandeur. We once imagined the great Step Pyramid before there was a pyramid. How did we do that? Black people lived through over four hundred years of rabid, hostile, savage, dehumanization yet never became rabid, hostile, savage dehumanizing people. Our way, our worldview, our narrative, our normativity is what allowed us to do this. This is what we need to revisit.

Black Mental Health pt. 2

By Tanya Dennis

With the global COVID-19 pandemic, we knew the world would never be the same. For some, COVID-19 has provided an opportunity to correct a society filled with bias, inequality, and meanness.

For Dr. Wade Nobles, long-time scholar/activist, and co-founder of the Association of Black Psychologists, “This is our time of reckoning. It is a time to redo what we have always done, sometimes under the radar, always in opposition to white supremacy. This is the time for Black people to interlock, reconnect and heal our community without European influence.”

Dr. Nobles, the Bay Area Chapter of the Association of Black Psychologists, and Oakland Frontline Healers are bringing together the best minds and calling on every sector to join them in the development of African American Wellness Hubs and an African American Healing Center in Oakland.

“Restoring wellness is to make the whole well. It is to connect everything and everyone in life affirming ways throughout the entire African world. Our way of being well and whole were well established in our past. In the past we gathered and found solutions collectively. Remember rent parties, Sunday church special offerings to send a child off to college or visiting the sick and shut in? These are our examples. In our way, personhood, familyhood, neighborhood, peoplehood, all the “hoods” are of equal importance. We can’t have a sick community and think our people will be well.”

Nobles and colleagues, after surveying and talking with Black people in Black communities across the nation, designed a detailed written plan for an African American Wellness Hub Complex. They envision a hub that is linked spiritually and psychologically, as a place where wellness and wholeness is real and ethnically authentic. Nobles said, “In many places our children are failing in school, many of our children are feeling they have no value, are being demeaned and assaulted. We need to take charge of these places. If teachers don’t love our children, they cannot ignite in them a desire to know and a passion for learning. If law enforcement doesn’t have high regard and deep respect for Black people, they will never understand that to ‘serve and protect’ means to be life affirming in what they do.”

“A big part of our new normal is to have in our thought, beliefs, and behavior the best of our wisdom, traditions and restorative practice available. This means to have in place living learning laboratories that are unapologetically devoted to our wellness, e.g., a wellness hub complex with healing centers. To have an exceptional and extraordinary place to bring people together and take them from hostile angry dis-at-ease producing places to places where we can work in harmony, create in dignity, and live to inspire life and ways of being that is affirming.”

Alameda County has stepped forward and is committed to establishing a Black Mental Health facility in partnership with the Association of Black Psychologists. The Association is grateful to Alameda County but notes four or five locations are necessary considering the amount of damage and illness that needs to be undone in the Black community.

Nobles says, “We must create a space, place and time that is guided by an African American wellness narrative that is awe-inspiring.” As an example of how important space is, he notes, “We tried to escape the blight and poverty of the inner city and move out to the suburbs, but all we did was go from inner city hostility to outer city hostility in the white enclave. At least in the inner city, our children didn’t lose their point of reference of belonging in the neighborhood or church. Healing spaces and places must be grounded in life affirming worldview and culture.”

“We must rescue and refine the best of Black ways. Look at our historical grandeur. We once imagined the great Step Pyramid before there was a pyramid. How did we do that? Black people lived through over four hundred years of rabid, hostile, savage, dehumanization yet never became rabid, hostile, savage dehumanizing people. Our way, our worldview, our narrative, our normativity is what allowed us to do this. This is what we need to revisit. We need a wellness place in our Black community where people can ‘imagine the better.’ A place where we can dismantle the ill and wrongfulness and recreate a vibrant affirming life spirit.”

Dr. Nobles says, “our new normal is the old African normal, where Black people inspired greatness just by living well and whole. Black people are a people of caring, sharing and daring. Our way was to care for our people, to share what we have, and to dare to be free. Our history records us having sacred places in nature where we would go to recreate our spirit of wellness. We need those places today and that’s why we need an African American Wellness Hub and healing centers.”

Activism

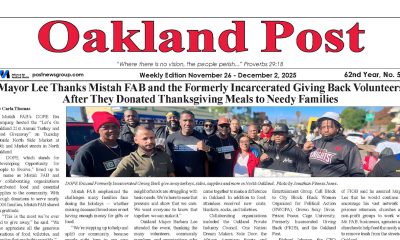

Oakland Post: Week of December 24 – 30, 2025

The printed Weekly Edition of the Oakland Post: Week of – December 24 – 30, 2025

To enlarge your view of this issue, use the slider, magnifying glass icon or full page icon in the lower right corner of the browser window.

Activism

Lu Lu’s House is Not Just Toying Around with the Community

Wilson and Lambert will be partnering with Mayor Barbara Lee on a toy giveaway on Dec. 20. Young people, like Dremont Wilkes, age 15, will help give away toys and encourage young people to stay in school and out of trouble. Wilkes wants to go to college and become a specialist in financial aid. Sports agent Aaron Goodwin has committed to giving all eight young people from Lu Lu’s House a fully paid free ride to college, provided they keep a 3.0 grade point average and continue the program. Lu Lu’s House is not toying around.

Special to the Post

Lu Lu’s House is a 501c3 organization based in Oakland, founded by Mr. Zirl Wilson and Mr. Tracy Lambert, both previously incarcerated. After their release from jail, they wanted to change things for the better in the community — and wow, have they done that!

The duo developed housing for previously incarcerated people, calling it “Lu Lu’s House,” after Wilson’s wonderful wife. At a time when many young people were robbing, looting, and involved in shootings, Wilson and Lambert took it upon themselves to risk their lives to engage young gang members and teach them about nonviolence, safety, cleanliness, business, education, and the importance of health and longevity.

Lambert sold hats and T-shirts at the Eastmont Mall and was visited by his friend Wilson. At the mall, they witnessed gangs of young people running into the stores, stealing whatever they could get their hands on and then rushing out. Wilson tried to stop them after numerous robberies and finally called the police, who Wilson said, “did not respond.” Having been incarcerated previously, they realized that if the young people were allowed to continue to rob the stores, they could receive multiple criminal counts, which would take their case from misdemeanors to felonies, resulting in incarceration.

Lu Lu’s House traveled to Los Angeles and obtained more than 500 toys

for a Dec. 20 giveaway in partnership with Oakland Mayor Barbara

Lee. Courtesy Oakland Private Industry,

Wilson took it upon himself to follow the young people home and when he arrived at their subsidized homes, he realized the importance of trying to save the young people from violence, drug addiction, lack of self-worth, and incarceration — as well as their families from losing subsidized housing. Lambert and Wilson explained to the young men and women, ages 13-17, that there were positive options which might allow them to make money legally and stay out of jail. Wilson and Lambert decided to teach them how to wash cars and they opened a car wash in East Oakland. Oakland’s Initiative, “Keep the town clean,” involved the young people from Lu Lu’s House participating in more than eight cleanup sessions throughout Oakland. To assist with their infrastructure, Lu Lu’s House has partnered with Oakland’s Private Industry Council.

For the Christmas season, Lu Lu’s House and reformed young people (who were previously robbed) will continue to give back.

Lu Lu’s House traveled to Los Angeles and obtained more than 500 toys.

Wilson and Lambert will be partnering with Mayor Barbara Lee on a toy giveaway on Dec. 20. Young people, like Dremont Wilkes, age 15, will help give away toys and encourage young people to stay in school and out of trouble. Wilkes wants to go to college and become a specialist in financial aid. Sports agent Aaron Goodwin has committed to giving all eight young people from Lu Lu’s House a fully paid free ride to college, provided they keep a 3.0 grade point average and continue the program. Lu Lu’s House is not toying around.

Activism

Desmond Gumbs — Visionary Founder, Mentor, and Builder of Opportunity

Gumbs’ coaching and leadership journey spans from Bishop O’Dowd High School, Oakland High School, Stellar Prep High School. Over the decades, hundreds of his students have gone on to college, earning academic and athletic scholarships and developing life skills that extend well beyond sports.

Special to the Post

For more than 25 years, Desmond Gumbs has been a cornerstone of Bay Area education and athletics — not simply as a coach, but as a mentor, founder, and architect of opportunity. While recent media narratives have focused narrowly on challenges, they fail to capture the far more important truth: Gumbs’ life’s work has been dedicated to building pathways to college, character, and long-term success for hundreds of young people.

A Career Defined by Impact

Gumbs’ coaching and leadership journey spans from Bishop O’Dowd High School, Oakland High School, Stellar Prep High School. Over the decades, hundreds of his students have gone on to college, earning academic and athletic scholarships and developing life skills that extend well beyond sports.

One of his most enduring contributions is his role as founder of Stellar Prep High School, a non-traditional, mission-driven institution created to serve students who needed additional structure, belief, and opportunity. Through Stellar Prep numerous students have advanced to college — many with scholarships — demonstrating Gumbs’ deep commitment to education as the foundation for athletic and personal success.

NCAA football history was made this year when Head Coach from

Mississippi Valley State, Terrell Buckley and Head Coach Desmond

Gumbs both had starting kickers that were women. This picture was

taken after the game.

A Personal Testament to the Mission: Addison Gumbs

Perhaps no example better reflects Desmond Gumbs’ philosophy than the journey of his son, Addison Gumbs. Addison became an Army All-American, one of the highest honors in high school football — and notably, the last Army All-Americans produced by the Bay Area, alongside Najee Harris.

Both young men went on to compete at the highest levels of college football — Addison Gumbs at the University of Oklahoma, and Najee Harris at the University of Alabama — representing the Bay Area on a national level.

Building Lincoln University Athletics From the Ground Up

In 2021, Gumbs accepted one of the most difficult challenges in college athletics: launching an entire athletics department at Lincoln University in Oakland from scratch. With no established infrastructure, limited facilities, and eventually the loss of key financial aid resources, he nonetheless built opportunities where none existed.

Under his leadership, Lincoln University introduced:

- Football

- Men’s and Women’s Basketball

- Men’s and Women’s Soccer

Operating as an independent program with no capital and no conference safety net, Gumbs was forced to innovate — finding ways to sustain teams, schedule competition, and keep student-athletes enrolled and progressing toward degrees. The work was never about comfort; it was about access.

Voices That Reflect His Impact

Desmond Gumbs’ philosophy has been consistently reflected in his own published words:

- “if you have an idea, you’re 75% there the remaining 25% is actually doing it.”

- “This generation doesn’t respect the title — they respect the person.”

- “Greatness is a habit, not a moment.”

Former players and community members have echoed similar sentiments in public commentary, crediting Gumbs with teaching them leadership, accountability, confidence, and belief in themselves — lessons that outlast any single season.

Context Matters More Than Headlines

Recent articles critical of Lincoln University athletics focus on logistical and financial hardships while ignoring the reality of building a new program with limited resources in one of the most expensive regions in the country. Such narratives are ultimately harmful and incomplete, failing to recognize the courage it takes to create opportunity instead of walking away when conditions are difficult.

The real story is not about early struggles — it is about vision, resilience, and service.

A Legacy That Endures

From founding Stellar PREP High School, to sending hundreds of students to college, to producing elite athletes like Addison Gumbs, to launching Lincoln University athletics, Desmond Gumbs’ legacy is one of belief in young people and relentless commitment to opportunity.

His work cannot be reduced to headlines or records. It lives on in degrees earned, scholarships secured, leaders developed, and futures changed — across the Bay Area and beyond.

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoLIHEAP Funds Released After Weeks of Delay as States and the District Rush to Protect Households from the Cold

-

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of November 26 – December 2, 2025

-

Alameda County3 weeks ago

Alameda County3 weeks agoSeth Curry Makes Impressive Debut with the Golden State Warriors

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoSeven Steps to Help Your Child Build Meaningful Connections

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoSeven Steps to Help Your Child Build Meaningful Connections

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoTrinidad and Tobago – Prime Minister Confirms U.S. Marines Working on Tobago Radar System

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoThanksgiving Celebrated Across the Tri-State

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoTeens Reject Today’s News as Trump Intensifies His Assault on the Press