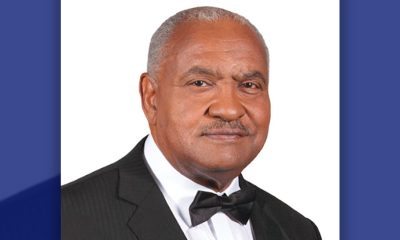

By Sharyn L. Flanagan Tribune Magazine Editor

When I found out that Lorraine Branham, dean of the S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications at Syracuse University, had died Tuesday after battling cancer, it didn’t just hit me hard because she was a Philadelphia native.

It hit me because Lorraine, a Philadelphia Tribune alumna, brought me down from The North Penn Reporter to Florida, to be on the copy desk at The Tallahassee Democrat. Lorraine was not only the first African-American editor-in-chief but the first female editor-in-chief. She didn’t just break barriers; she smashed them to smithereens.

I can honestly say that Lorraine taught me more than any other executive editor I’ve ever had.

I’ll always remember when I first went into her office for my interview in December 1996, I smiled because seeing her in that position was inspiring. “Us Philly girls have to stick together,” she said, and I beamed even more.

My best memory of her is when she first met my father, who was visiting me from Philadelphia. I took him on a tour of the newsroom and introduced him around. Then Lorraine, who had an open-door policy, asked my father to come in and talk to her. I was a little tense about this prospect because my father didn’t have a filter.

Well, he didn’t disappoint.

He slowly stepped into her office, looked Lorraine up and down a few times and then out came: “Mmm mmm mmm … do you have some great gams on you!” I was mortified! Lorraine laughed, then smiled that gorgeous broad smile of hers and ushered him farther into the office. I think they discussed how things were changing in Philly. But I honestly can’t remember because I was busy cursing out my father in my head.

From that point on, Lorraine always inquired about my father. They were fast friends. Even after I left the newspaper in September 1999, I would see Lorraine at National Association of Black Journalists’ gatherings and she would ask about my dad, always with a smile on her face.

As a trailblazing newsroom leader, Lorraine set the bar high. She always told us “no one is allowed to complain when my door is always open.” And she meant that.

When it was time to make some big changes to increase our circulation, Lorraine went all out. We got rid of the traditional newsroom setup and even the usual titles.

She asked each one of us to write down what one thing we feared most about the impending changes on flash paper and then brought in a guy who held a rising flame for us to throw our doubts and fears up in smoke. The moment moved me.

Lorraine wanted us to change our mindset in a big way. I was rejuvenated and optimistic about what was next.

She also wanted to be sure that people wouldn’t keep on calling the paper “The Tallahassee Dixiecrat.” She was a next-level kind of manager. She had faith in the staff and pushed us to do more.

Lorraine was the first executive editor to ever promote me. I went from copy editor all the way to day coordinator (city editor) in quick fashion. She made me want to learn more, do more and be more.

Lorraine never let my own doubts hold me back — because she had faith in me. She was a true leader and believed in nurturing the next generation. When I asked her to be my mentor, she said, “Sure, but don’t you think it’s time that you mentor someone yourself?” Whoa, what a concept!

And if there were some hard truths along the way, Lorraine was candid about that. When I had decided to lock my hair, she took me in her office and cautioned me that it could affect me professionally. She told me that “hair is political, even if you don’t mean it to be.” Lorraine had put me on the management track and she wanted me to stay there.

Then when I decided to leave The Democrat in 1999 for USA Today, she told me she didn’t agree with my decision because even though it was a bigger operation, it wasn’t a management position. She had helped me get an offer to be an assistant managing editor out West, but I needed to be closer to my family in Philadelphia.

Lorraine’s legacy is in all those she managed, mentored, guided and taught. A great editor, colleague, teacher and sister-friend is gone, but she has left many others to carry on her work.

There will be a viewing from 11 a.m. to 1 p.m. Thursday, April 11, followed by a funeral service at Sharon Baptist Church, 3955 Conshohocken Ave., Philadelphia. Donations may be made to the Lorraine Branham Scholarship Fund at the Klein College of Media and Communications at Temple University, 2020 N. 13th St., Philadelphia, PA 19122.

This article originally appeared in The Philadelphia Tribune.

Business4 weeks ago

Business4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks ago

Arts and Culture4 weeks ago

Arts and Culture4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks ago