National

Few Blacks Elected State Prosecutors

By Jazelle Hunt

NNPA Washington Correspondent

WASHINGTON (NNPA) – Of the 46 states that elect prosecutors, more than half – 27 – have no known African Americans, according to a report by the Women Donors Network, an organization of progressive women philanthropists and advocates, which examined the demographics of state prosecutors who had been elected into their positions as of summer 2014.

“The whole thing honestly is so shocking,” says Brenda Choresi Carter, director of the Reflective Democracy Campaign. “Just the stunning absence of Black prosecutors even in states where we know there is a historic and well-developed Black electorate…came as a surprise.”

The study, which is part of the organization’s Reflective Democracy Campaign, was unable to verify the race and gender of 165 elected state prosecutors. White people account for 95 percent of the verified ranks (79 men, 16 percent women). In some states, including Tennessee and Washington, there are no elected prosecutors of color.

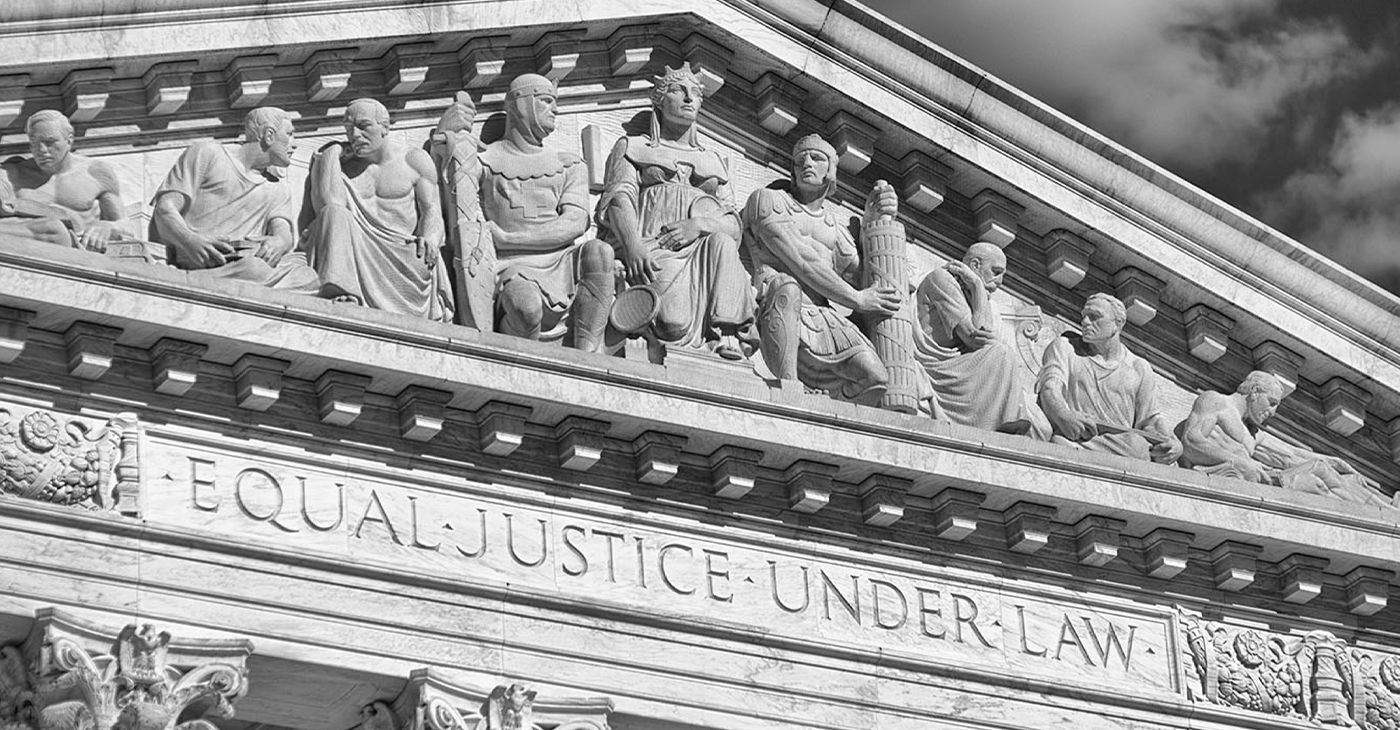

State prosecutors’ offices investigate crimes and are the highest criminal prosecutors in their cities, counties, or other municipalities. They are often the ultimate decision-makers in a wide range of criminal proceedings, from charges, to sentencing, to appeals and parole.

Compounding the problem is that the legal profession is one of the least diverse professions in the U.S. Whites are 88.1 percent of all lawyers, compared to 4.8 percent who are Black, 3.7 percent Latino and 3.4 percent Asians. Seventy percent are males. By comparison, Whites are 81 percent of architects and engineers and 72 percent of physicians and surgeons.

“The irony of the prosecutor is that in many ways they have more direct power over people’s lives than most other elected offices. All the points along the process of pursing a [criminal] case…are subject to a prosecutor’s own individual discretion,” Carter says.

“If these [powers] are concentrated in the hands of a demographic group that does not have the experience being a person of color in America, or a woman…it’s difficult to see how they would understand the full range of the impact of their decisions.”

Nobody has to explain that to Philadelphia’s R. Seth Williams, who became the first Black elected district attorney in the state of Pennsylvania in 2009. It’s an unusual position for a Black man, but one he says more people of color should consider.

“People think if you are a member of a minority group you should be a defense attorney, but as a state prosecutor I have much more power than a defense attorney,” he explained.

“I can not charge [someone] or not pursue the death penalty, I can get drug programs started for those who need it, I can create veteran offenders programs…. A district attorney has the power and discretion to do the right thing.”

Williams is one of just 62 Black elected state prosecutors across the country, out of 2,444 total – less than 3 percent.

One of Williams’ proudest, and most controversial actions was becoming the first D.A. in the country to successfully prosecute a Catholic clergy member in connection to the sex abuse scandal. He has also prosecuted white-collar criminals, and has reduced the number of criminal charges filed in small drug-related cases. His goal is to be smart on crime, not just tough – even if it means ruffling feathers.

“I wanted to show that we’d apply the same standard of justice to everyone, regardless of your last name, who your father is, the zip code you live in, or what your race is,” he says, adding that his office pursued people from all walks of life, “not just going after the corner boys for selling bags of weed.”

While most state prosecutors are hired or appointed, the Women Donors Network study focused on those elected because they theoretically represent voters. In these cases, aspiring prosecutors must run a political campaign; but the study points out that 85 percent of incumbent prosecutors run unopposed for their reelections. Carter says a lack of financial, social, and political access perpetuate an “old boys’ club” in government.

“There is a real issue with the fact of access to the ballot…. There are people who will never even run for office, or be in state government, or be a state judge because they cant afford it, not because they aren’t good or don’t have brilliant ideas. They don’t have access to the money, the donors, the ballot the same way others do,” she explained.

“What we see in elected offices overall is that it’s a pretty closed system. What we see with prosecutors is all of that plus more.”

Williams agrees.

“We need many more concerned, caring, empathetic, outstanding attorneys to become state prosecutors. We also need people who better reflect the communities we serve, to become prosecutors.”

###

Activism

‘Donald Trump Is Not a God:’ Rep. Bennie Thompson Blasts Trump’s Call to Jail Him

“Donald Trump is not a god,” U.S. Rep. Bennie Thompson, D-Miss., told The Grio during a recent interview, reacting to Trump’s unsupported claims that the congressman, along with other committee members like vice chair and former Republican Rep. Liz Cheney, destroyed evidence throughout the investigation.

By Post Staff

U.S. Rep. Bennie Thompson, D-Miss., said he not intimidated by President-elect Donald Trump, who, during an interview on “Meet the Press,” called for the congressman to be jailed for his role as chairman of the special congressional committee investigating Trump’s role in the Jan. 6, 2021, mob attack on the U.S. Capitol.

“Donald Trump is not a god,” Thompson told The Grio during a recent interview, reacting to Trump’s unsupported claims that the congressman, along with other committee members like vice chair and former Republican Rep. Liz Cheney, destroyed evidence throughout the investigation.

“He can’t prove it, nor has there been any other proof offered, which tells me that he really doesn’t know what he’s talking about,” said the 76-year-old lawmaker, who maintained that he and the bipartisan Jan. 6 Select Committee – which referred Trump for criminal prosecution – were exercising their constitutional and legislative duties.

“When someone disagrees with you, that doesn’t make it illegal; that doesn’t even make it wrong,” Thompson said, “The greatness of this country is that everyone can have their own opinion about any subject, and so for an incoming president who disagrees with the work of Congress to say ‘because I disagree, I want them jailed,’ is absolutely unbelievable.”

When asked by The Grio if he is concerned about his physical safety amid continued public ridicule from Trump, whose supporters have already proven to be violent, Thompson said, “I think every member of Congress here has to have some degree of concern, because you just never know.”

This story is based on a report from The Grio.

Activism

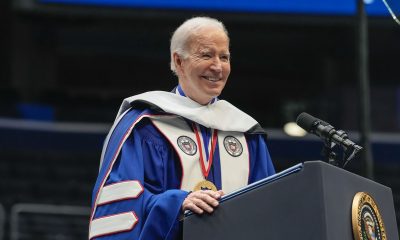

Biden’s Legacy Secured with Record-Setting Black Judicial Appointments

His record surpasses previous efforts by his predecessors. President Jimmy Carter appointed 37 Black judges, including seven Black women. In stark contrast, Donald Trump’s first term resulted in only two Black women appointed out of 234 lifetime judicial nominations. The White House said Biden’s efforts show a broader commitment to racial equity and justice.

By Stacy M. Brown

WI Senior Writer

President Joe Biden’s commitment to diversifying the federal judiciary has culminated in a historic achievement: appointing 40 Black women to lifetime judgeships, the most of any president in U.S. history.

Biden has appointed 62 Black judges, cementing his presidency as one focused on promoting equity and representation on the federal bench.

His record surpasses previous efforts by his predecessors. President Jimmy Carter appointed 37 Black judges, including seven Black women. In stark contrast, Donald Trump’s first term resulted in only two Black women appointed out of 234 lifetime judicial nominations.

The White House said Biden’s efforts show a broader commitment to racial equity and justice.

Meanwhile, Trump has vowed to dismantle key civil rights protections, including the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division.

“Having the Black woman’s experience on the federal bench is extremely important because there is a different kind of voice that can come from the Black female from the bench,” Delores Jones-Brown, professor emeritus at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, told reporters.

Lena Zwarensteyn of the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights told reporters that these district court judges are often the first and sometimes the final arbiters in cases affecting healthcare access, education equity, fair hiring practices, and voting rights.

“Those decisions are often the very final decisions because very few cases actually get heard by the U.S. Supreme Court,” Zwarensteyn explained.

Biden’s nomination of Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson to the Supreme Court further reflects his commitment to judicial diversity. Jackson became the first Black woman to serve on the nation’s highest court.

Patrick McNeil, spokesperson for the Leadership Conference, pointed out that over half of Biden’s Black female judicial appointees have backgrounds as civil rights attorneys and public defenders, experience advocates consider essential for a balanced judiciary.

Meanwhile, Congress remains divided over the expansion of federal judgeships. Legislation to add 66 new judgeships—approved unanimously by the Senate in August—stalled in the GOP-controlled House until after the election. House Republicans proposed distributing the new judgeships over the next decade, giving three administrations a say in appointments. President Biden, however, signaled he would veto the bill if it reached his desk.

Rep. Jerry Nadler, D-N.Y., argued the delay was a strategic move to benefit Trump’s potential return to office. “Donald Trump has made clear that he intends to expand the power of the presidency and giving him 25 new judges to appoint gives him one more tool at his disposal,” Nadler said.

#NNPA BlackPress

California, Districts Try to Recruit and Retain Black Teachers; Advocates Say More Should Be Done

SACRAMENTO OBSERVER — Many Black college students have not considered a teaching career because they have never had a Black teacher, said Preston Jackson, who teaches physical education at California Middle School in Sacramento. Those who consider a teaching career are often deterred by the cost of teacher preparation, taking required tests and unpaid student teaching.

A Series by EdSource | The Sacramento Observer

Recruiting and retaining Black teachers has taken on new urgency in recent years as California lawmakers try to ease the state’s teacher shortage. The state and individual school districts have launched initiatives to recruit teachers of color, but educators and advocates say more needs to be done.

Hiring a diverse group of teachers helps all students, but the impact is particularly significant for students of color, who then score higher on tests and are more likely to graduate from college, according to the Learning Policy Institute. A recently released report also found that Black boys are less likely to be identified for special education when they have a Black teacher.

In the last five years, state lawmakers have made earning a credential easier and more affordable and have offered incentives for school staff to become teachers — all moves meant to ease the teacher shortage and help to diversify the educator workforce.

Despite efforts by the state and school districts, the number of Black teachers doesn’t seem to be increasing. Black teachers say that to keep them in the classroom, teacher preparation must be more affordable, pay and benefits increased, and more done to ensure they are treated with respect, supported and given opportunities to lead.

“Black educators specifically said that they felt like they were being pushed out of the state of California,” said Jalisa Evans, chief executive director of the Black Educator Advocates Network of a recent survey of Black teachers. “When we look at the future of Black educators for the state, it can go either way, because what Black educators are feeling right now is that they’re not welcome.”

Task force offers recommendations

State Superintendent of Public Instruction Tony Thurmond called diversifying the teacher workforce a priority and established the California Department of Education Educator Diversity Advisory Group in 2021.

The advisory group has made several recommendations, including beginning a public relations campaign and offering sustained funding to recruit and retain teachers of color, and providing guidance and accountability to school districts on the matter. The group also wants universities, community groups and school districts to enter into partnerships to build pathways for teachers of color.

Since then, California has created a set of public service announcements and a video to help recruit teachers and has invested $10 million to help people of color to become school administrators, said Travis Bristol, chairman of the advisory group and an associate professor of education at UC Berkeley. Staff from county offices of education also have been meeting to share ideas on how they can support districts’ efforts to recruit and retain teachers of color, he said.

The state also has invested more than $350 million over the past six years to fund teacher residency programs, and recently passed legislation to ensure residents are paid a minimum salary. Residents work alongside an experienced teacher-mentor for a year of clinical training while completing coursework in a university preparation program — a time commitment that often precludes them from taking a job.

Legislators have also proposed a bill that would require that student teachers be paid. Completing the 600 hours of unpaid student teaching required by the state, while paying for tuition, books, supplies and living expenses, is a challenge for many Black teacher candidates.

Black teacher candidates typically take on much more student debt than their white counterparts, in part, because of the large racial wealth gap in the United States. A 2019 study by the Economic Policy Institute showed that the median white family had $184,000 in family wealth (property and cash), while the median Latino family had $38,000 and the median Black family had $23,000.

Lack of data makes it difficult to know what is working

It’s difficult to know if state efforts are working. California hasn’t released any data on teacher demographics since the 2018-19 school year, although the data is submitted annually by school districts. The California Department of Education (CDE) did not provide updated data or interviews requested by EdSource for this story.

The most recent data from CDE shows the number of Black teachers in California declined from 4.2% in 2009 to 3.9% during the 2018-19 school year. The National Center for Education Statistics data from the 2020-21 show that Black teachers made up 3.8% of the state educator workforce.

Having current data is a critical first step to understanding the problem and addressing it, said Mayra Lara, director of Southern California partnerships and engagement at The Education Trust-West, an education research and advocacy organization.

“Let’s be clear: The California Department of Education needs to annually publish educator demographic and experience data,” Lara said. “It has failed to do so for the past four years. … Without this data, families, communities and decision-makers really are in the dark when it comes to the diversity of the educator workforce.”

LA Unified losing Black teachers despite efforts

While most state programs focus on recruiting and retaining all teachers of color, some California school districts have initiatives focused solely on recruiting Black teachers.

The state’s largest school district, Los Angeles Unified, passed the Black Student Excellence through Educator Diversity, Preparation and Retention resolution two years ago. It required district staff to develop a strategic plan to ensure schools have Black teachers, administrators and mental health workers, and to advocate for programs that offer pathways for Black people to become teachers.

When the resolution was passed, in February 2022, Los Angeles Unified had 1,889 Black teachers — 9% of its teacher workforce. The following school year, that number declined to 1,823 or 7.9% of district teachers. The number of Black teachers in the district has gone down each year since 2016. The district did not provide data for the current school year.

Robert Whitman, director of the Educational Transformation Office at LA Unified, attributed the decrease, in part, to the difficulty attracting teachers to the district, primarily because of the area’s high cost of living.

“Those who are coming out of colleges now, in some cases, we find that they can make more money doing other things,” Whitman said. “And so, they may not necessarily see education as the most viable option.”

The underrepresentation of people of color prompted the district to create its own in-house credentialing program, approved by the California Commission on Teacher Credentialing, Whitman said. The program allows classified staff, such as substitute teachers, paraprofessionals, administrative assistants and bus drivers, to become credentialed teachers while earning a salary and benefits at their original jobs.

Grow-your-own programs such as this, and the state’s Classified School Employee Credentialing program, and a soon-to-be launched apprenticeship program, are meant to diversify the educator workforce because school staff recruited from the community more closely match the demographics of the student body than traditionally trained and recruited teachers, according to research.

Los Angeles Unified has other initiatives to increase the number of Black educators in the district, Whitman said, including working with universities and colleges to bring Black teachers, counselors and psychiatric social workers to their campuses. The district also has programs that help school workers earn a credential for free, and channels employees completing a bachelor’s degree toward the district’s teacher preparation program where they can begin teaching while earning their credential.

All new teachers at Los Angeles Unified are supported by mentors and affinity groups, which have been well received by Black teachers, who credit them with inspiring and helping them to see themselves as leaders in the district, Whitman said.

Oakland has more Black teachers than students

Recruiting and retaining Black teachers is an important part of the Oakland Unified three-year strategic plan, said Sarah Glasband, director of recruitment and retention for the district. To achieve its goals, the district has launched several partnerships that make an apprenticeship program, and a residency program that includes a housing subsidy, possible. A partnership with the Black Teacher Project, a nonprofit advocacy organization, offers affinity groups, workshops and seminars to support the district’s Black teachers.

The district also has a Classified School Employee Program funded by the state and a new high school program to train future teachers. District pathway programs have an average attrition rate of less than 10%, Glasband said.

This year, 21.3% of the district’s K-12 teachers are Black, compared with 20.3% of their student population, according to district data. Oakland Unified had a retention rate of about 85% for Black teachers between 2019 and 2023.

Better pay, a path to leadership will help teachers stay

Black teachers interviewed by EdSource and researchers say that to keep them in the classroom, more needs to be done to make teacher preparation affordable, improve pay and benefits, and ensure they are treated with respect, supported and given opportunities to lead.

The Black Educator Advocates Network came up with five recommendations after surveying 128 former and current Black teachers in California about what it would take to keep them in the classroom:

- Hire more Black educators and staff

- Build an anti-racist, culturally responsive and inclusive school environment

- Create safe spaces for Black educators and students to come together

- Provide and require culturally responsive training for all staff

- Recognize, provide leadership opportunities and include Black educators in decision making

Teachers interviewed by EdSource said paying teachers more also would make it easier for them to stay.

“I don’t want to say that it’s the pay that’s going to get more Black teachers,” Brooke Sims, a Stockton teacher, told EdSource. “But you get better pay, you get better health care.”

The average teacher salary in the state is $88,508, with the average starting pay at $51,600, according to the 2023 National Education Association report, “State of Educator Pay in America.” California’s minimum living wage was $54,070 last year, according to the report.

State efforts, such as an initiative that pays teachers $5,000 annually for five years after they earn National Board Certification, will help with pay parity across school districts, Bristol said. Teachers prove through assessments and a portfolio that they meet the National Board for Professional Teaching Standards. To be eligible for the grant, teachers must work at least half of their time in a high-needs school. Teachers who qualify are also given $2,500 to cover the cost of certification.

This incentive will help teachers continue their education and improve their practice, said Los Angeles teacher Petrina Miller. “It’s awesome,” she said.

Teacher candidates must be actively recruited

Many Black college students have not considered a teaching career because they have never had a Black teacher, said Preston Jackson, who teaches physical education at California Middle School in Sacramento. Those who consider a teaching career are often deterred by the cost of teacher preparation, taking required tests and unpaid student teaching.

“In order to increase the number of Black teachers in schools, it has to become deliberate,” Jackson said. “You have to actively recruit and actively seek them out to bring them into the profession.”

Since starting in 2005, Jackson has been one of only a handful of Black teachers at his school.

“And for almost every single one of my kids, I’m the first Black teacher they’ve ever had,” said Jackson. “… And for some of them, I’m the first one they’ve ever seen.”

Mentors are needed to help retain new teachers

Mentor teachers are the key ingredient to helping new Black educators transition successfully into teaching, according to teachers interviewed by EdSource. Alicia Simba says she could have taken a job for $25,000 more annually in a Bay Area district with few Black teachers or students but opted to take a lower salary to work in Oakland Unified.

But like many young teachers, Simba knew she wanted mentors to help her navigate her first years in the classroom. She works alongside Black teachers in Oakland Unified who have more than 20 years of teaching experience. One of her mentor teachers shared her experience of teaching on the day that Martin Luther King Jr. was shot. Other teachers told her about teaching in the 1980s during the crack cocaine epidemic.

“It really helps dispel some of the sort of narratives that I hear, which is that being a teacher is completely unsustainable,” Simba said. “Like, there’s no way that anyone could ever be a teacher long term, which are things that, you know, I’ve heard my friends say, and I’ve thought it myself.”

The most obvious way to retain Black teachers would be to make sure they are treated the same as non-Black teachers, said Brenda Walker, a Black teacher and president of the Associated Chino Teachers.

“If you are a district administrator, site administrator, site or colleague, parent or student, my bachelor’s degree, master’s degree, and my special education credential are just as valuable and carry as much weight, and are as respected as any other educator,” she said.

“However, it’s just as critical for all those groups to acknowledge and respect the unique cultural experience I bring to the table and acknowledge and respect that I’m a proud product of my ancestral history.”

Black teachers: how to recruit THEM and make them stay

This is the first part of a special series by EdSource on the recruitment and retention of Black teachers in California. The recruitment and hiring of Black educators has lagged, even as a teacher shortage has given the task new urgency.

____________________________________________________________

Photo Caption:

Website Tags and Keywords:

Twitter Tags/Handles:

-

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of November 20 – 26, 2024

-

California Black Media3 weeks ago

California Black Media3 weeks agoCalifornia to Offer $43.7 Million in Federal Grants to Combat Hate Crimes

-

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks agoAn Inside Look into How San Francisco Analyzes Homeless Encampments

-

California Black Media3 weeks ago

California Black Media3 weeks agoCalifornia Department of Aging Offers Free Resources for Family Caregivers in November

-

Black History3 weeks ago

Black History3 weeks agoEmeline King: A Trailblazer in the Automotive Industry

-

California Black Media3 weeks ago

California Black Media3 weeks agoGov. Newsom Goes to Washington to Advocate for California Priorities

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoOCCUR Hosts “Faith Forward” Conference in Oakland

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoPRESS ROOM: Clyburn, Pressley, Scanlon, Colleagues Urge Biden to Use Clemency Power to Address Mass Incarceration Before Leaving Office