Black History

First African-American Resident Physician at VUMC

THE TENNESSEE TRIBUNE — Harold Jordan, MD was the first African-American resident physician at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Dr. Harold Willoughby Jordan is the second grandson of Dr. John Henry Jordan and was born in the house in Newnan that John built. Harold was raised there in the shadow of his grandfather. He spent his childhood playing with John’s old medical bag, surrounded by his medical books and lasting legacy. From a young age, it was Harold’s desire to become a doctor, and he knew his parents expected it of him.

Harold was educated in Newnan and finished high school there before relocating to Atlanta to attend Morehouse College. He graduated from Morehouse with a bachelor’s degree in Biology in 1958 and then followed in his grandfather’s and great-grandfather’s footsteps by enrolling as a student at Meharry Medical College. Harold graduated in 1962 and completed one year of a residency in internal medicine before deciding to pursue psychiatry instead. He was the first black medical resident on record at Vanderbilt University.

After completing his education, Harold became a faculty member at Meharry Medical College and served as Chairman of the Department of Psychiatry for 18 years as well as Acting Dean of the School of Medicine. He was loyal to Meharry and only left in the 1970’s to serve as the first black Commissioner of Mental Health for the State of Tennessee. A state building, the Harold W. Jordan Habilitation Center, is named in his honor.

February 8, 2019 marked the launch of the newest of the named lectures in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences – the Dr. Harold Jordan Diversity and Inclusion Lecture.

Harold Jordan, MD was the first African-American resident physician at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, completing a general psychiatry residency between 1964 and 1967. Dr. Jordan’s history with the Department of Psychiatry and Vanderbilt University School of Medicine was outlined in the article “Hidden Figure” from the Summer 2017 issue of Vanderbilt Medicine Magazine.

Harold Jordan, M.D., has had a distinguished medical career that includes many highlights, including being chair of Psychiatry at Meharry Medical College, his medical alma mater, and serving as acting dean of the School of Medicine at Meharry as well.

Besides his academic career, Jordan was devoted to improving mental health care for the public through governmental service. He was Assistant Commissioner for Psychiatric Services and, following that, Commissioner of Mental Health and Mental Retardation for the state of Tennessee, and performed those jobs with such distinction that the state named a building in his honor on the campus of Clover Bottom Developmental Center, the state facility for people with severe intellectual disabilities which closed in 2016.

But a lesser-known part of Jordan’s professional life is his role as a pioneer at Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC). In 1964 he became the first African-American resident physician at VUMC.

It’s fair to say that he began that groundbreaking achievement with little fanfare, and it’s fair to say that the achievement has received little fanfare since.

Reached at his home in California, where he moved after retirement, Jordan recalled interviewing with William F. Orr Jr., M.D., who was chair of Psychiatry at Vanderbilt from 1947 to 1969.

“Dr. Lloyd Elam arranged for me to meet Dr. Orr,” he said. With bemused understatement, and the hint of a chuckle, he added, “Obviously, that was very good for me.”

Elam, who later served as President of Meharry, was on the Psychiatry faculty at that institution and recommended that Jordan, who had already done an internship year at Meharry in Internal Medicine, consider a slot at Vanderbilt because, at the time, Meharry did not offer a residency in Psychiatry.

The interview went well, and Orr offered Jordan one of the three residency slots in Psychiatry that year.

But, Jordan recalls, Orr did more than offer him a position.

“Dr. Orr was very encouraging, accepting and protective,” Jordan said, clearly recalling a time when not all institutions exhibited those attitudes toward African-Americans. “He made it clear that I would be accepted. I felt secure. I knew the path was clear for me.”

Jordan’s family roots in medicine are deep; both his great-grandfather and grandfather were physicians who trained at Meharry. When he was growing up in Newnan, Georgia, just south of Atlanta, he heard family tales of his medical forbears and was inspired to follow their footsteps.

“I had wanted to do that since I heard about them,” he said.

Despite the low-key nature with which Jordan’s residency was handled, the groundbreaking nature of what was going on would have been known to all of the participants.

Vanderbilt’s first African-American student, Joseph Johnson Jr., was admitted to the Divinity School in 1953, and in 1956 two black law students had been admitted as well. But despite the presence of a few black students on campus, at that time there were no African-American residents at Vanderbilt Hospital, and it would be two more years, 1966, before the Vanderbilt School of Medicine would admit its first African-American student, Levi Watkins Jr.

“He paved the way for everyone who came after him,” Churchwell said. “To be an African-American resident in a sea of white residents at a Southern medical institution, I would call him a true Robinson Crusoe.”

Just as Vanderbilt was changing in that era, so was the country. As it happened, the day after Jordan began his residency at VUMC, July 1, 1964, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, mandating an end to discrimination in public accommodations.

Jordan says the faculty and his fellow residents were encouraging and supportive—“My colleagues were fine—there were no problems in Psychiatry”—but the unusual sight for that time of an African-American physician at Vanderbilt sometimes made for awkward misunderstandings.

“I walked into the Emergency Room [for a consult] and somebody thought I was the janitor and said, ‘The trash is over there,’” he remembered.

From across the decades of an honored career in medicine, Jordan, who turned 80 this year, says he has no ill feeling about such slights. “I would laugh at them, like, ‘What are you talking about?’” he said.

After his three years of residency at VUMC, Jordan pursued his academic career at Meharry and his public service career with the State of Tennessee, but also maintained a clinical appointment on the faculty of the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine until 2016.

In a 1971 letter in support of Jordan’s faculty appointment at Vanderbilt, Robert M. Reed, M.D., a Psychiatry faculty member of that era, wrote that, since Jordan was the first black resident to train at Vanderbilt, “his original appointment and subsequent performance were watched and monitored by a great many people as constituting something of a ‘test case.’”

He adds, “If indeed it were a test, then Harold passed it with honors, in my opinion.”

Andre Churchwell, M.D., Chief Diversity Officer for Vanderbilt University Medical Center, senior associate dean for Diversity Affairs, and Levi Watkins Jr. M.D. Chair, professor of Medicine, Biomedical Engineering and Radiology and Radiological Sciences, said that Jordan’s contributions to VUMC are important to remember.

“He paved the way for everyone who came after him,” Churchwell said. “To be an African-American resident in a sea of white residents at a Southern medical institution, I would call him a true Robinson Crusoe.”

A 1967 Psychiatry departmental group photo makes Churchwell’s point. It shows 40 or so people lined up around the traditional entrance to the School of Medicine, and Jordan is indeed the only African-American in a sea of white faces.

Given the varieties of reactions to Jordan’s presence and his role at the Medical Center in the mid-1960s, Churchwell added, “The fact that he was studying psychiatry probably helped him.”

For his part, Jordan says his time at Vanderbilt was important to him, both personally and professionally.

“It was a very positive influence,” he said. “I just felt very supported at both Meharry and Vanderbilt. I felt blessed to have had that experience in Psychiatry.”

He is married to Geraldine Crawford Jordan, a Meharry Medical College nursing school graduate. Thy have four children: Harold, Vincent, Karen and Kristi, as well as four grandchildren.

This article originally appeared in The Tennessee Tribune.

Activism

Oakland Post: Week of November 26 – December 2, 2025

The printed Weekly Edition of the Oakland Post: Week of November 26 – December 2, 2025

To enlarge your view of this issue, use the slider, magnifying glass icon or full page icon in the lower right corner of the browser window.

Activism

Oakland Post: Week of November 19 – 25, 2025

The printed Weekly Edition of the Oakland Post: Week of November 19 – 25, 2025

To enlarge your view of this issue, use the slider, magnifying glass icon or full page icon in the lower right corner of the browser window.

Activism

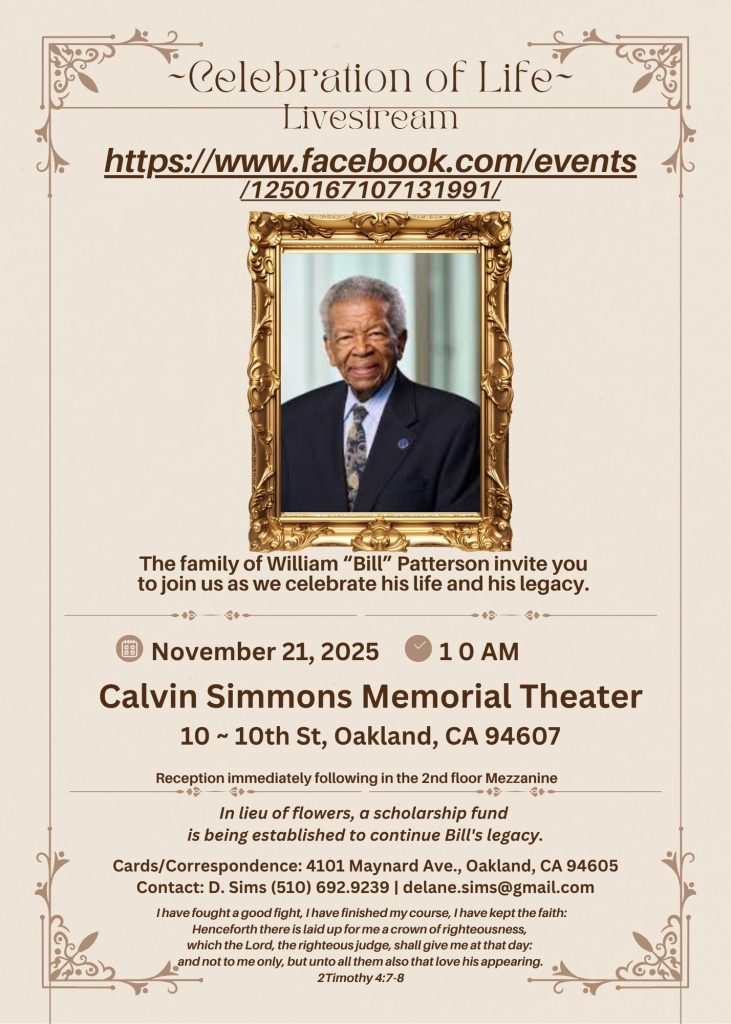

IN MEMORIAM: William ‘Bill’ Patterson, 94

Bill devoted his life to public service and education. In 1971, he became the founding director for the Peralta Community College Foundation, he also became an administrator for Oakland Parks and Recreation overseeing 23 recreation centers, the Oakland Zoo, Children’s Fairyland, Lake Merritt, and the Henry J. Kaiser Convention Center.

William “Bill” Patterson, 94, of Little Rock, Arkansas, passed away peacefully on October 21, 2025, at his home in Oakland, CA. He was born on May 19, 1931, to Marie Childress Patterson and William Benjamin Patterson in Little Rock, Arkansas. He graduated from Dunbar High School and traveled to Oakland, California, in 1948. William Patterson graduated from San Francisco State University, earning both graduate and undergraduate degrees. He married Euradell “Dell” Patterson in 1961. Bill lovingly took care of his wife, Dell, until she died in 2020.

Bill devoted his life to public service and education. In 1971, he became the founding director for the Peralta Community College Foundation, he also became an administrator for Oakland Parks and Recreation overseeing 23 recreation centers, the Oakland Zoo, Children’s Fairyland, Lake Merritt, and the Henry J. Kaiser Convention Center.

He served on the boards of Oakland’s Urban Strategies Council, the Oakland Public Ethics Commission, and the Oakland Workforce Development Board.

He was a three-term president of the Oakland branch of the NAACP.

Bill was initiated in the Gamma Alpha chapter of Kappa Alpha Psi Fraternity.

In 1997 Bill was appointed to the East Bay Utility District Board of Directors. William Patterson was the first African American Board President and served the board for 27 years.

Bill’s impact reached far beyond his various important and impactful positions.

Bill mentored politicians, athletes and young people. Among those he mentored and advised are legends Joe Morgan, Bill Russell, Frank Robinson, Curt Flood, and Lionel Wilson to name a few.

He is survived by his son, William David Patterson, and one sister, Sarah Ann Strickland, and a host of other family members and friends.

A celebration of life service will take place at Henry J. Kaiser Convention Center (Calvin Simmons Theater) on November 21, 2025, at 10 AM.

His services are being livestreamed at: https://www.facebook.com/events/1250167107131991/

In lieu of flowers, donations can be made to the Euradell and William Patterson scholarship fund TBA.

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of November 12 – 18, 2025

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoIN MEMORIAM: William ‘Bill’ Patterson, 94

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoHow Charles R. Drew University Navigated More Than $20 Million in Fed Cuts – Still Prioritizing Students and Community Health

-

Bay Area3 weeks ago

Bay Area3 weeks agoNo Justice in the Justice System

-

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks agoThe Perfumed Hand of Hypocrisy: Trump Hosted Former Terror Suspect While America Condemns a Muslim Mayor

-

#NNPA BlackPress2 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress2 weeks agoTrump’s Death Threat Rhetoric Sends Nation into Crisis

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoProtecting Pedophiles: The GOP’s Warped Crusade Against Its Own Lies

-

#NNPA BlackPress2 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress2 weeks agoLewis Hamilton set to start LAST in Saturday Night’s Las Vegas Grand Prix