Opinion

Op-Ed: How to Protect Our Communities From Homegrown Terrorism

By Rev. Dr. William J. Barber II and Jonathan Wilson-Hartgrove

Since the Republican presidential front-runner announced after San Bernardino that he would close America’s borders to Muslims, a debate has ensued about what “radicalization” means and how far we as a nation are willing to go to protect ourselves from it. So-called liberals (and even some in the Republican party’s mainstream) have said, “Not all Muslims have been radicalized.”

To this Donald Trump retorts, “Until we know which ones have been, let’s keep them all out.” The unquestioned consensus in America’s public square is that we can only be safe by figuring out who the un-American terrorists are and getting rid of them.

But where we’re from in North Carolina, we should not be so naive. We have a disproportionate share of homegrown terrorists.

Before he moved to Colorado to carry out his attack on the Planned Parenthood clinic in Colorado Springs, Colorado, Robert Dear was apparently radicalized in the mountains of western North Carolina.

After assassinating Reverend Clementa Pinckney and eight other members of Mother Emanuel AME church in Charleston, South Carolina, Dylann Roof fled to Shelby, North Carolina, a hotbed of Klan activity, where he was apprehended by authorities.

We must assume that Craig Hicks was radicalized in liberal Chapel Hill before shooting three of his Muslim neighbors.

But we do not call any of these men radical Christians. Why, then, do we so easily accept the language of “radical Islam”?

When we look closely at the acts of terror that rend our communities and make everyone feel less safe, the common denominator is not a particular religion or culture.

It is, instead, a violence that is perpetuated by those who use fear to gain political power. We cannot combat this violence by naming an enemy to eliminate. Instead, we must illuminate the sort of friendships that make fusion politics possible.

The politics of fear is a politics that demands violence.

When we met nearly 20 years ago, we were the most unlikely of partners. Reverend Barber, an African-American pastor with deep roots in the civil-rights community, was serving as chair of the Human Relations Commission for Democratic Governor Jim Hunt. Jonathan, a Southern Baptist from Stokes County, had just finished an internship with Republican Senator Strom Thurmond, one-time Dixiecrat candidate for president. Ideology and established enemy lines all but guaranteed we’d never work together. But we got to know each other’s love for people and for this state. We learned that we share a common faith and, with it, a concern for the common good.

A “Southern strategy” was developed in the late 1960s to pit us against each other, creating a “solid South” for the Republican Party by dividing poor and working people according to their worst fears about their neighbors. Black and white have a long history in this place, but political strategists worked carefully to “color” immigrants, members of the LGBTQ community, and religious minorities, casting them as un-American rather than non-white. The rise of ISIS as a real and credible threat means that this racist form of political manipulation can take the form of calling Muslims un-American.

But we must not allow the candidates of either party to condemn the murders in San Bernadino without acknowledging their own role in this nation’s violence. The politics of fear is a politics that demands violence. What is more, it is used to exercise political violence by those who wield power. After her husband was gunned down in 1968 for challenging our violent culture, Coretta Scott King boldly said:

In this society violence against poor people and minority groups is routine. I remind you that starving a child is violence; suppressing a culture is violence; neglecting schoolchildren is violence; discrimination against a working man is violence; ghetto house is violence; ignoring medical needs is violence; contempt for equality is violence; even a lack of will power to help humanity is a sick and sinister form of violence.

Our friendship had helped us to see through the divide-and-conquer tactics of this violent politics. Friendships like this played an essential role in North Carolina’s political history. When Samuel Ashley and J.W. Hood—a white minister and a black minister—came together after the Civil War to help rewrite our state’s constitution, they noted that “beneficent provision for the poor is the first duty” of state government.

Like those two men, Black Republicans and poor white Populists throughout this state saw their common cause in the 1890s and joined together to form a Fusion Party that won every statewide election in 1896.

The white-supremacy campaign of 1898, which led to a coup in Wilmington and ushered in the Jim Crow era, was a violent reaction against the power of fusion friendships.

The rhetoric of fear, we know, cannot save us.

Once again in the mid-20th century, black and white came together in North Carolina, giving rise to the modern civil-rights movement. After the legal victories of desegregation, the Voting Rights Act, and the Fair Housing Act, the Southern strategy of intentional division was implemented as a calculated reaction against the power of fusion friendship in the public square.

We have witnessed the power of friendships like ours in the Moral Movement that arose in North Carolina in 2005, bringing together a broad coalition of more than 200 organizations that recognize we have more in common than those who would divide us want us to believe.

Our coalition partners demonstrated their power in the 2008 presidential election when North Carolina’s Electoral College votes went to a Democrat, breaking the solid South.

This victory led to yet another violent backlash of mystery money, gerrymandering, and the extreme makeover of our state government in the 2013 legislative session. “Moral Mondays” became the largest state-based civil-disobedience campaign in US history because fusion friendships like ours refused to give into extremists’ assault.

What, then, can we do to make our community safe again and prevent the “radicalization” of extreme elements in our society. The rhetoric of fear, we know, cannot save us. To say “radical Islam” is to play the race card again in the 21st century.

As in our past, fusion friendships offer a way forward. As we say in the Moral Movement, “Forward together, not one step back.”

This article originally appeared at Sojourners. “ The Third Reconstruction,” the authors’ forthcoming book,was released by Beacon Press in January 2016.

Activism

2025 in Review: Seven Questions for Assemblymember Lori Wilson — Advocate for Equity, the Environment, and More

Her rise has also included several historic firsts: she is the only Black woman ever appointed to lead the influential Assembly Transportation Committee, and the first freshman legislator elected Chair of the California Legislative Black Caucus. She has also been a vocal advocate for vulnerable communities, becoming the first California legislator to publicly discuss being the parent of a transgender child — an act of visibility that has helped advanced representation at a time when political tensions related to social issues and culture have intensified.

By Edward Henderson, California Black Media

Assemblymember Lori D. Wilson (D-Suisun City) joined the California Legislature in 2022 after making history as Solano County’s first Black female mayor, bringing with her a track record of fiscal discipline, community investment, and inclusive leadership.

She represents the state’s 11th Assembly District, which spans Solano County and portions of Contra Costa and Sacramento Counties.

Her rise has also included several historic firsts: she is the only Black woman ever appointed to lead the influential Assembly Transportation Committee, and the first freshman legislator elected Chair of the California Legislative Black Caucus. She has also been a vocal advocate for vulnerable communities, becoming the first California legislator to publicly discuss being the parent of a transgender child — an act of visibility that has helped advanced representation at a time when political tensions related to social issues and culture have intensified.

California Black Media spoke with Wilson about her successes and disappointments this year and her outlook for 2026.

What stands out as your most important achievement this year?

Getting SB 237 passed in the Assembly. I had the opportunity to co-lead a diverse workgroup of colleagues, spanning a wide range of ideological perspectives on environmental issues.

How did your leadership contribute to improving the lives of Black Californians this year?

The Black Caucus concentrated on the Road to Repair package and prioritized passing a crucial bill that remained incomplete during my time as chair, which establishes a process for identifying descendants of enslaved people for benefit eligibility.

What frustrated you the most this year?

The lack of progress made on getting Prop 4 funds allocated to socially disadvantaged farmers. This delay has real consequences. These farmers have been waiting for essential support that was promised. Watching the process stall, despite the clear need and clear intent of the voters, has been deeply frustrating and reinforces how much work remains to make our systems more responsive and equitable.

What inspired you the most this year?

The resilience of Californians persists despite the unprecedented attacks from the federal government. Watching people stay engaged, hopeful, and determined reminded me why this work matters and why we must continue to protect the rights of every community in our state.

What is one lesson you learned this year that will inform your decision-making next year?

As a legislator, I have the authority to demand answers to my questions — and accept nothing less. That clarity has strengthened my approach to oversight and accountability.

In one word, what is the biggest challenge Black Californians are facing currently?

Affordability and access to quality educational opportunities.

What is the goal you want to achieve most in 2026?

Advance my legislative agenda despite a complex budget environment. The needs across our communities are real, and even in a tight fiscal year, I’m committed to moving forward policies that strengthen safety, expand opportunity, and improve quality of life for the people I represent.

Activism

2025 in Review: Seven Questions for Assemblymember Tina McKinnor, Champion of Reparations, Housing and Workers’ Rights

In 2025, McKinnor pushed forward legislation on renters’ protections, re-entry programs, reparations legislation, and efforts to support Inglewood Unified School District. She spoke with California Black Media about the past year and her work. Here are her responses.

By Joe W. Bowers Jr., California Black Media

Assemblymember Tina McKinnor (D-Inglewood) represents

California’s 61st Assembly District.

As a member of the California Legislative Black Caucus (CLBC),

McKinnor was elected in 2022. She chairs the Los Angeles County Legislative Delegation and leads the Assembly Public Employment and Retirement Committee. McKinnor also served as a civic engagement director, managed political campaigns, and worked as chief of staff for former Assemblymembers Steven Bradford and Autumn Burke.

In 2025, McKinnor pushed forward legislation on renters’ protections, re-entry programs, reparations legislation, and efforts to support Inglewood Unified School District. She spoke with California Black Media about the past year and her work. Here are her responses.

Looking back on 2025, what do you see as your biggest win?

Assembly Bill (AB) 628. If rent is $3,000, people should at least have a stove and a refrigerator. It’s ridiculous that people were renting without basic appliances.

I’m also proud that I was able to secure $8.4 million in the state budget for people coming home from incarceration. That includes the Homecoming Project, the menopause program for incarcerated women, and the Justice Leaders Program.

How did your leadership help make life better for Black Californians this year?

After the Eaton Fire, I pushed to get the same kind of support for affected areas that wealthier regions get after disasters.

I also did a lot of work building political power— establishing the Black Legacy PAC and California for All of Us PAC so we could support Black candidates and educate voters. We also called voters to make sure they understood Prop 50.

People need to understand this: there are only 12 Black legislators in the Capitol. Folks act like we can just walk in and pass reparations, but that’s not how it works.

What frustrated you most this year?

The governor did not have the political will to sign these bills: AB 57 and AB 62. They both passed overwhelmingly in the Assembly and the Senate. We did the work. The only person who didn’t have the political will to sign them was the governor.

The public needs to ask the governor why he didn’t sign the bills. We can’t keep letting people off the hook. He has to answer.

I also introduced AB 51 — the bill to eliminate interest payments on Inglewood Unified School District’s long-standing state loan — held in the Appropriations Committee. That was frustrating,

What inspired you most in 2025?

The civil rights trip to Alabama was life changing. We visited the Legacy Museum and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice. We took members of the Black, Latino, Jewish, and API caucuses with us. It changed all of us.

People aren’t always against us — they just don’t know our history.

What’s one lesson from 2025 that will shape how you approach decisions next year?

The legislative trip to Norway taught me that collaboration matters. Government, labor, and industry sit down together there. They don’t make villains. Everybody doesn’t get everything they want, but they solve problems.

What’s the biggest challenge facing Black Californians in one word?

Inequity. It shows up in housing, wealth, stress – all these things.

What’s the number one goal you want to accomplish in 2026?

Bringing back AB 57 and AB 62, and securing money for the Inglewood Unified loan interest forgiveness.

Advice

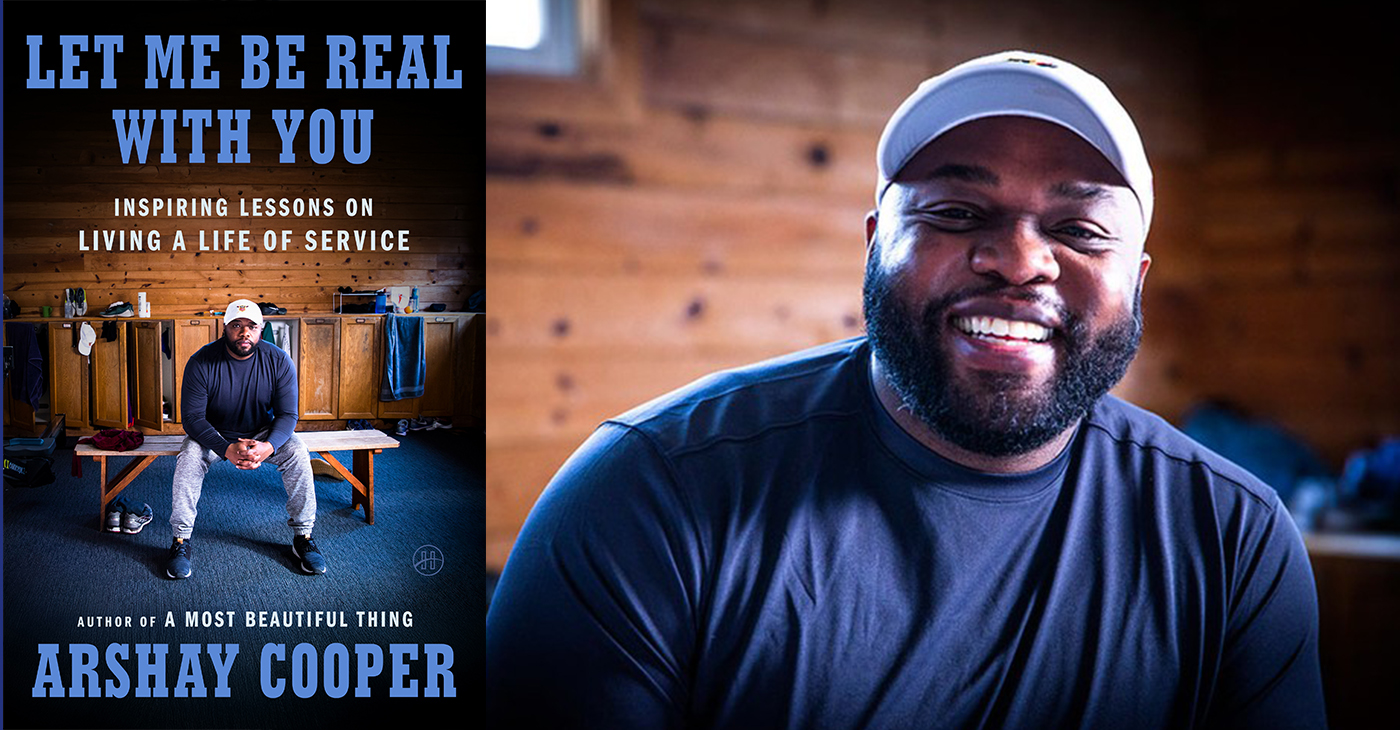

BOOK REVIEW: Let Me Be Real With You

At first look, this book might seem like just any other self-help offering. It’s inspirational for casual reader and business reader, both, just like most books in this genre. Dig a little deeper, though, and you’ll spot what makes “Let Me Be Real With You” stand out.

By Terri Schlichenmeyer

Author: Arshay Cooper, Copyright: c.2025, Publisher: HarperOne, SRP: $26.00, Page Count: 40 Pages

The hole you’re in is a deep one.

You can see the clouds above, and they look like a storm; you sense the wind, and it’s cold. It’s dark down there, and lonesome, too. You feel like you were born there — but how do you get out of the deep hole you’re in? You read the new book “Let Me Be Real With You” by Arshay Cooper. You find a hand-up and bring someone with you.

In the months after his first book was published, Cooper received a lot of requests to speak to youth about his life growing up on the West Side of Chicago, his struggles, and his many accomplishments. He was poor, bullied, and belittled, but he knew that if he could escape those things, he would succeed. He focused on doing what was best, and right. He looked for mentors and strove to understand when opportunities presented themselves.

Still, his early life left him with trauma. Here, he shows how it’s overcome-able.

We must always have hope, Cooper says, but hope is “merely the catalyst for action. The hope we receive must transform into the hope we give.”

Learn to tell your own story, as honestly as you know it. Be open to suggestions, and don’t dismiss them without great thought. Know that masculinity doesn’t equal stoicism; we are hard-wired to need other people, and sharing “pain and relatability can dissipate shame and foster empathy in powerful ways.”

Remember that trauma is intergenerational, and it can be passed down from parent to child. Let your mentors see your potential. Get therapy, if you need it; there’s no shame in it, and it will help, if you learn to trust it. Enjoy the outdoors when you can. Learn self-control. Give back to your community. Respect your financial wellness. Embrace your intelligence. Pick your friends and relationships wisely. “Do it afraid.”

And finally, remember that “You were born to soar to great heights and rule the sky.”

You just needed someone to tell you that.

At first look, this book might seem like just any other self-help offering. It’s inspirational for casual reader and business reader, both, just like most books in this genre. Dig a little deeper, though, and you’ll spot what makes “Let Me Be Real With You” stand out.

With a willingness to discuss the struggles he tackled in the past, Cooper writes with a solidly honest voice that’s exceptionally believable, and not one bit dramatic. You won’t find unnecessarily embellished stories or tall tales here, either; Cooper instead uses his real experiences to help readers understand that there are few things that are truly insurmountable. He then explains how one’s past can shape one’s future, and how today’s actions can change the future of the world.

“Let Me Be Real With You” is full of motivation, and instruction that’s do-able for adults and teens. If you need that, or if you’ve vowed to do better this coming year, it might help make you whole.

-

Alameda County4 weeks ago

Alameda County4 weeks agoSeth Curry Makes Impressive Debut with the Golden State Warriors

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoLIHEAP Funds Released After Weeks of Delay as States and the District Rush to Protect Households from the Cold

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoSeven Steps to Help Your Child Build Meaningful Connections

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoSeven Steps to Help Your Child Build Meaningful Connections

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoTeens Reject Today’s News as Trump Intensifies His Assault on the Press

-

Bay Area2 weeks ago

Bay Area2 weeks agoPost Salon to Discuss Proposal to Bring Costco to Oakland Community meeting to be held at City Hall, Thursday, Dec. 18

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoFBI Report Warns of Fear, Paralysis, And Political Turmoil Under Director Kash Patel

-

Activism2 weeks ago

Activism2 weeks agoMayor Lee, City Leaders Announce $334 Million Bond Sale for Affordable Housing, Roads, Park Renovations, Libraries and Senior Centers