New Journal and Guide

O’Rourke In Norfolk

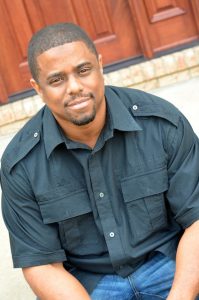

NEW JOURNAL AND GUIDE — 2020 Democratic Presidential Candidate Beto O’Rourke campaigned in Norfolk on Tuesday (April 16). with a stop at Charlie’s American Café on Granby St. Beto (as he is affectionately known) was greeted and joined by Norfolk Delegate Jay Jones.

By Randy Singleton

NORFOLK – 2020 Democratic Presidential Candidate Beto O’Rourke campaigned in Norfolk on Tuesday (April 16). with a stop at Charlie’s American Café on Granby St. Beto (as he is affectionately known) was greeted and joined by Norfolk Delegate Jay Jones.

Beto is the first of 18 democratic presidential candidates to visit the Hampton Roads area. Current polls have Beto O’Rourke in a 3-way tie for fourth place in a crowded democratic field.

He ranks third in fundraising, outpaced only by Bernie Sanders and Pete Buttigieg. He continued with visits to the Peninsula and Richmond.

This article originally appeared in the New Journal and Guide.

#NNPA BlackPress

Black-Owned Newspapers and Media Companies Are Small Businesses Too!

NNPA NEWSWIRE — “Dear World, the entire planet is feeling the devastation of the coronavirus pandemic,” Cheryl Smith of Texas Metro News wrote to her readers. “We must be concerned about ourselves, as well as others. You may be aware that the media is considered ‘essential.’ So, guess what? We have a responsibility, a moral obligation to use this status to be a source of information, support, and inspiration, just as we are at all other times,” Smith wrote.

Financial Support is Essential to Delivery of These Essential Services

By Stacy M. Brown, NNPA Newswire Senior Correspondent

@StacyBrownMedia

Publishers of Black-owned community newspapers, including Janis Ware of the Atlanta Voice, Cheryl Smith of Texas Metro News, Chris Bennett of the Seattle Medium, Denise Rolark Barnes of the Washington Informer, and Brenda Andrews of the New Journal & Guide in Virginia, are desperately trying to avoid shuttering operations.

On Wednesday, April 29, Rolark Barnes, Andrews, Bennett, and Ware will participate in a special livestream broadcast to discuss how their publications are enduring as the pandemic rages on.

In a heartfelt and straight-to-the-point op-ed published recently, Ware explained to her tens of thousands of readers that The Atlanta Voice has boldly covered the issues that affect the African American community.

“Our founders, Mr. J. Lowell Ware and Mr. Ed Clayton, were committed to the mission of being a voice to the voiceless with the motto of, ‘honesty, integrity and truth,’” Ware wrote in an article that underscores the urgency and importance of African American-owned newspapers during the coronavirus pandemic. Ware has established a COVID-19 news fund and aggregated the Atlanta Voice’s novel coronavirus coverage into a special landing page within its website.

To remain afloat, Ware and her fellow publishers know that financial backing and support will be necessary. Following the spread of the pandemic, many advertisers have either paused their ad spending or halted it altogether. And other streams of revenue have also dried up, forcing Black-owned publications to find ways to reduce spending and restructure what were already historically tight budgets.

With major companies like Ruth Chris Steakhouse and Pot Belly Sandwiches swooping in and hijacking stimulus money aimed at small businesses, the Black Press — and community-based publishing in general — has been largely left out of the $350 billion stimulus and Paycheck Protection Program packages.

To make matters worse, there are no guarantees that a second package, specifically focused on small business, will benefit Black publishers or other businesses owned by people of color.

Publications like the New Journal and Guide, Washington Informer (which recently celebrated its 55th anniversary) and the Atlanta Voice have been essential to the communities they serve — and the world at large for 193 years.

Unfortunately for some publishers, the impact of COVID-19 has brought business operations to a near halt. While none are thriving, some publishers have developed ingenious and innovative ways to continue operations.

“Dear World, the entire planet is feeling the devastation of the coronavirus pandemic,” Cheryl Smith of Texas Metro News wrote to her readers. “We must be concerned about ourselves, as well as others. You may be aware that the media is considered ‘essential.’ So, guess what? We have a responsibility, a moral obligation to use this status to be a source of information, support, and inspiration, just as we are at all other times,” Smith wrote.

Smith’s statements echo the more than 200 African American-owned newspapers in the NNPA family. The majority of the publications are owned and operated by women, and virtually all are family dynasties so rarely seen in the black community.

The contributions of the Black Press remain indelibly associated with the fearlessness, determination, and success of Black America.

Those contributions include the works of Frederick Douglass, WEB DuBois, Patrice Lumumba, Kwame Nkrumah, and former NNPA Chairman Dr. Carlton Goodlett.

Douglas, who helped slaves escape to the North while working with the Underground Railroad, established the abolitionist paper, “The North Star,” in Rochester, New York.

He developed it into the most influential black anti-slavery newspaper published during the Antebellum era.

The North Star denounced slavery and fought for the emancipation of women and other oppressed groups with a motto of “Right is of no Sex – Truth is of no Color; God is the Father of us all, and we are all brethren.”

DuBois, known as the father of modern Pan Africanism, demanded civil rights for Blacks but freedom for Africa and an end to capitalism, which he called the cause of racism and all human misery.

Many large news organizations have begun targeting African Americans and other audiences of color by either acquiring Black-owned news startups or adding the moniker “Black” to the end of their brand. However, it was Black-owned and operated news organizations that were on the front lines for voting rights, civil rights, ending apartheid, fair pay for all, unionization, education equity, healthcare disparities and many other issues that disproportionately negatively impact African Americans.

Today, the Black Press continues to reach across the ocean where possible to forge coalitions with the growing number of websites and special publications that cover Africa daily from on the continent, Tennessee Tribune Publisher Rosetta Perry noted.

The evolution of the Black Press, the oldest Black business in America, had proprietors take on issues of chattel slavery in the 19th century, Jim Crow segregation and lynching, the great northern migration, the Civil Rights Movement, the transformation from the printing press to the digital age and computerized communication.

With the Plessy vs. Ferguson Supreme Court ruling that said no black man has any rights that a white man must honor, there came a flood of Black publications to advocate for Black rights and to protest the wrongs done to Blacks.

An expose in Ebony Magazine in 1965 alerted the world to a Black female engineer, Bonnie Bianchi, who was the first woman to graduate from Howard University in Electrical Engineering.

It was through the pages of the Black Press that the world learned the horrors of what happened to Emmett Till.

The Black Press continues to tackle domestic and global issues, including the novel coronavirus pandemic and its effects on all citizens – particularly African Americans.

It was through the pages of the Black Press that the world learned that COVID-19 was indeed airborne and that earlier estimates by health experts were wrong when they said the virus could last only up to 20 to 30 minutes on a surface.

Now, it’s universally recognized that the virus can last for hours on a surface and in the air.

“A few short weeks ago, life as we know it, was pretty different,” Ware told her readers. “These are unprecedented times, and we are working around the clock to provide the best possible coverage, sometimes taking risks to keep Metro Atlanta informed.”

Tune in to the livestream at www.Facebook.com/BlackPressUSA.

#NNPA BlackPress

60 Years Ago: Students Launched Sit-In Movement

NNPA NEWSWIRE — Violent episodes were the exceptions and not the rule of the massively spreading Sit-in Movement. In nearly all sit-in cities, black protesters made immeasurable efforts to avoid violence at all cost since the movement and training centered on non-violent demonstrations in confronting inequality.

Dr. Kelton Edmonds is a Professor of History at California University of Pennsylvania. His primary research is on Black Student Activism in the United States. He is a native of Portsmouth, VA and graduated from I.C. Norcom High school in 1993.

By Dr. Kelton Edmonds, Special to The New Journal and Guide

February 1, 2020 marks the 60th anniversary of the launch of the historic Sit-in Movement, when four African-American freshmen from North Carolina A&T State College (now University) in Greensboro, NC sparked the non-violent and student-led wave of protests that ultimately resulted in the desegregation of F.W. Woolworth and other racially discriminatory stores.

The brave freshmen from NCA&T, who would later be adorned with the iconic label of the “Greensboro Four”, consisted of David Richmond, Franklin McCain, Joseph McNeil, and Ezell Blair Jr. (Jibreel Khazan). On February 1, 1960, the Greensboro Four bought items at Woolworth’s, then sat at the ‘whites-only’ lunch counter and refused to leave until they were served. Although waitresses refused to serve them, in accordance with the store’s racist policies, the four would continue their protest and in the following days and weeks would be joined by more students from NCA&T, the nearby all-women’s HBCU Bennett College and students from other nearby colleges and high schools.

In a 2003 interview, Khazan (formerly Blair, Jr.) reflected on the daily threats of violence and verbal assaults from white antagonists, as one caller reached him on the dorm hall phone and bellowed, “…executioners are going to kill you niggers if you come back down here tomorrow, you and your crazy friends.”

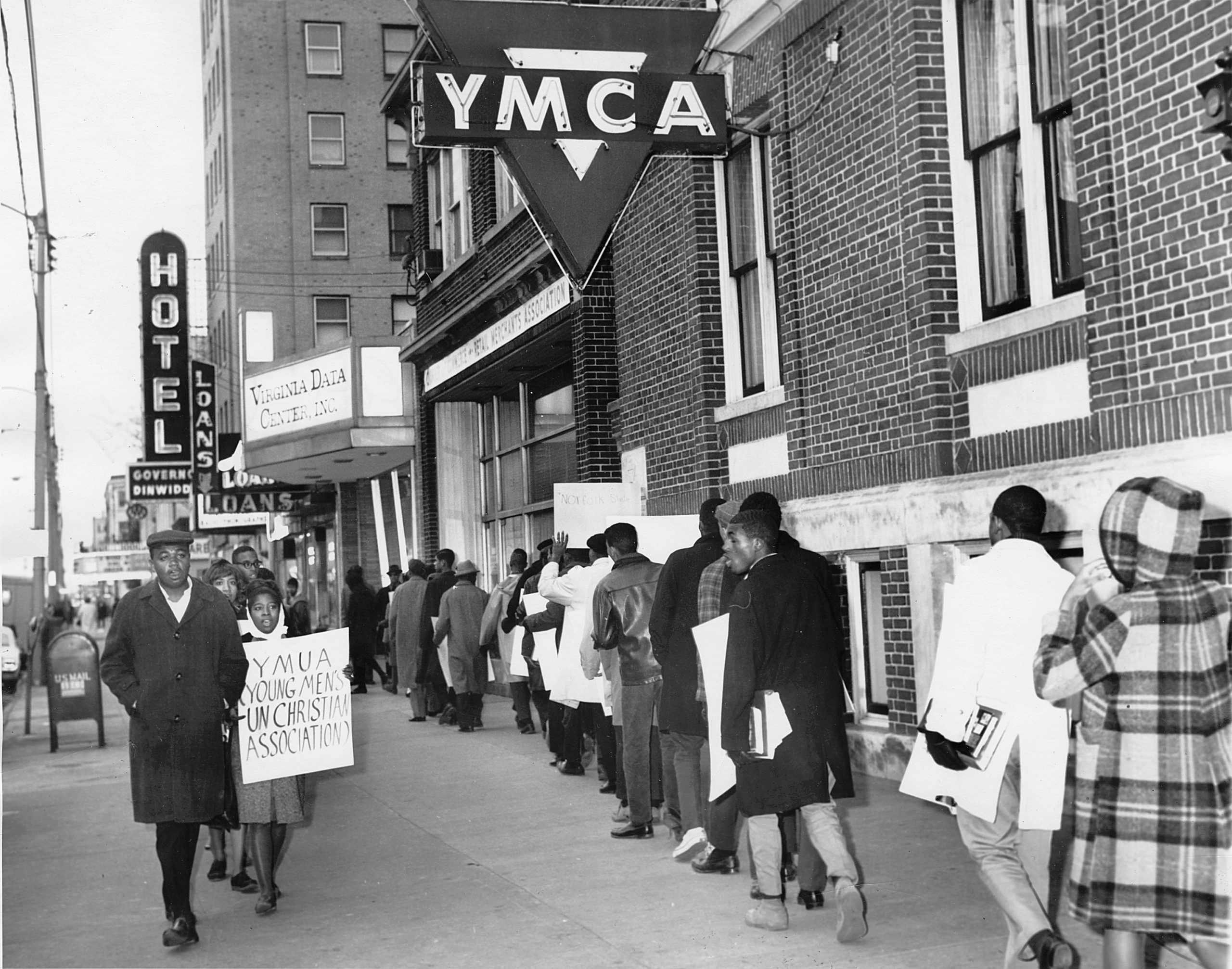

Students from Norfolk’s Booker T. Washington High School stage set in at Granby Street’s Woolworth’s lunch counter. Photo: New Journal and Guide Archives

White student allies who protested alongside black students were not immune from death threats either, as Khazan recalled a white student protester explaining that their college president was threatened by an anonymous caller saying, “…if those nigger loving bitches come downtown again and sit with those niggers, we going to kill them and burn your school down.”

The Greensboro students persisted nevertheless, and soon, the protests that flooded the lunch counters of the segregated store would spread to other cities throughout the South beginning in North Carolina cities such as Elizabeth City, Charlotte and Winston-Salem, in addition to cities in Virginia.

In Virginia

Virginia played a primary role in the Sit-in Movement, as Hampton, Virginia became the first community outside of North Carolina to experience sit-ins on February 10th.

Initially, three students from Hampton Institute sat-in at the downtown Woolworth’s lunch counter in Hampton and were refused service. As a testament to the veracity of the movement, within two weeks, over 600 students in Hampton were sitting-in.

On February 12th, sit-in protests spread to Norfolk, as 38 black protesters staged a sit-in at the Woolworth lunch counters on Granby and Freemason streets.

Similar demonstrations were held in Portsmouth, in the mid-city shopping center at lunch counters in Rose’s Department store on February 12th and at Bradshaw-Diehl department store later that week.

Led by students from I.C. Norcom High school, the Portsmouth sit-ins would be one of the few cities that experienced violence, albeit initiated by white anti-protesters armed with chains, hammers, and pipes and resulting in retaliation from the black students after being attacked.

Violent episodes were the exceptions and not the rule of the massively spreading Sit-in Movement. In nearly all sit-in cities, black protesters made immeasurable efforts to avoid violence at all cost since the movement and training centered on non-violent demonstrations in confronting inequality.

Edward Rodman, high school activist in Portsmouth, admitted they were initially unorganized and untrained in passive resistance, which played a role in their reactions to the violent anti-protesters. The Congress for Racial Equality (CORE) connected with the Portsmouth student protesters and over the next few days conducted intense and successful non-violent workshops with the young people. Soon after, the Portsmouth students reignited their movement without incidents of retaliation toward violent antagonists.

North of Hampton Roads, Richmond, Virginia experienced sit-ins as well as Baltimore, MD, and dozens of other cities by the end of February. By mid-April, sit-in protests reached all southern states involving thousands of black student activists and sympathizers.

The coordinated demonstrations of thousands of black student protesters and sympathizers put insurmountable pressure on Woolworth’s, as it became nearly impossible for regular customers to purchase items, eat at the lunch counters and even enter the store in many instances.

On May 25th, the sit-in movement received a major victory as lunch counters at Woolworth’s in Winston Salem, NC desegregated. Soon after, Woolworth’s in Nashville, TN and San Antonio, TX also integrated. Finally, on July 25, ground zero, Woolworth’s in Greensboro integrated its lunch counter. With the possibility of facing bankruptcy, F.W. Woolworth totally acquiesced and desegregated all of its lunch counters throughout the nation by the end of the summer of 1960.

The Legacies And Larger Significance Of The 1960 Sit-in Movement, Sparked In Greensboro

Similar to the successful 1955 Montgomery Bus Boycott, the students’ triumphant coordinated protests in 1960 further demonstrated how mass economic boycotts could lead to desegregationist social victories, particularly when targeting businesses that relied heavily on black patronage. The Greensboro Four only set out to challenge and change the discriminatory practices of the local Woolworth’s, yet their movement expanded exponentially to ultimately bring about the desegregation of all Woolworth’s lunch counters in the country.

Unidentified sit-in demonstration. Photo: New Journal and Guide Archives

The students of the Civil Rights era suddenly possessed a new weapon, the mass sit-in, which would continue to be used in Greensboro and around the country in various forms. The sit-ins combined with the freedom rides led to black students establishing their unique value and niche to the larger Civil Rights Movement. Black students understood their unique, collective power and desired to harness their efforts under a national apparatus. Consequently, another major legacy of the student movement that emerged in Greensboro was it also directly led to the birth of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in April of 1960 in nearby Raleigh, NC on the campus of Shaw University.

SNCC would soon emerge as one of the most formidable organizations of the decade, elevating students to the forefront of the Civil Rights Movement.

After marveling at the magnitude and effectiveness of the student protesters during the sit-ins, major Civil Rights organizations such as the NAACP, SCLC and CORE pressured the students to collapse their meteoric movement into the youth wing of one of their institutions under their supervision.

The students however, decided to remain autonomous and formulate their own student-led organization, while still adhering to non-violent principles. The students’ decision to remain student-led received noteworthy support from several key adult Civil Rights leaders in Greensboro in addition to Ella Baker from SCLC.

SNCC would prove to be an indispensible organization that not only championed directly confronting Jim Crow racism on numerous levels through organized protests and massive voter registration drives, but SNCC also further popularized the concept of participatory democracy and was the first major Civil Rights organization to evolve toward seriously embracing principles of black power ideology under Stokely Carmichael’s (Kwame Ture) leadership in 1966.

Another legacy of the 1960 sit-in movement was that it offered the inspiration and blueprint for the second and more colossal wave of mass student protest in Greensboro in 1963. The 1963 student demonstrations in Greensboro would be even more locally successful than their predecessor as they desegregated all remaining businesses in downtown Greensboro and the student leader of the second wave of sit-ins, Jesse Jackson, would parlay his leadership in the student protests onto the national Civil Rights stage throughout the 20th century. Similar to Greensboro, other cities throughout the South would experience a second and even third wave of similar protests to successfully desegregate other remaining businesses throughout the decade.

Ultimately, all mass student protests of the 1960s and thereafter owe their viability to the student-led Greensboro protests of 1960, including student black power activists and anti-war activists of the late 60s and 70s. Although its origins predate 1960, even one of the largest and most noteworthy national student organizations, Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), owe its resurgence and major elements of its effectiveness to the spark ignited by the Greensboro Four on February 1, 1960.

Even recent episodes of student activism exhibited in the Ferguson, Missouri protests of 2014-15, as well as the student protests led by black students at the University of Missouri in 2015, which ultimately led to the resignation of the chancellor, have attributes that correlate to the 1960 student movement. The student movement of 1960, ignited by the Greensboro Four, provided a blueprint for future students to build upon, perfect, and utilize in a variety of ways for a plethora of circumstances.

Most importantly, what happened in 1960 showed young people the power they possessed to address their grievances and ultimately bring about change on both local and national levels if they organized themselves and remained committed.

Unique Weapons for Non-violent Students

In addition to the typical traits that come along with youthfulness such as idealism and impatience, student success during the 1960 sit-ins and thereafter was directly affixed to two distinct assets possessed by students juxtaposed to their older adult activist counterparts. The first asset is condense demographics, as student-body populations were primarily located on campuses and/or nearby the colleges.

The fact that hundreds to thousands of students in a college town lived within a square mile of each other led to the expeditious mobilization of large numbers of people and efficient dissemination of information and strategy.

Although black churches proved to be invaluable throughout the Black Freedom Struggle from Reconstruction to the Civil Rights Movement, there was still no equivalent amongst the older black generation to the college campus’ effectiveness as both a meeting place and as a domicile for housing and dispersing the shock troops of the movement.

The second major asset specific to students would be the relation between arrest and reprisal. At some of their demonstrations prior to 1960, older black activists strategically triggered their arrests for charges such as trespassing or loitering as a way to dramatize unjust treatment via media coverage and to pressure white officials to change discriminatory laws.

Once mobilized per the sit-ins however, student activists were able to invite and withstand incarceration for far longer periods of time and in extremely larger numbers. Students vastly elevated this critical strategy of the overall movement. During 1960 and beyond, the enormous numbers unleashed by black student activists put unyielding pressure on local law enforcement, political officials and jail facilities. In many cities like Greensboro, there were not enough jail cells for all of the students arrested, particularly since the students refused bail and chose to remain incarcerated.

This action severely drained local municipalities of money and resources, forcing local governmental, business and law officials to dramatically adjust policies and sometimes change discriminatory laws. Student activists were able to perfect this strategy because they could endure prolonged imprisonment without fear of major job or housing reprisal.

Comparably, many older activists, whose families depended on their incomes, could not sacrifice prolonged periods of incarceration, as it would threaten their livelihood. Furthermore, angry employers or landlords, who disapproved of their protest activities, could threaten to fire them or abruptly remove them from property they were renting.

Students were not confronted with the same ramifications of these economic, employment and housing reprisals, as the majority of them lived on campuses and perhaps had part-time, albeit replaceable, minimum wage jobs, often with no dependents.

Drawing the contrast between student activists versus the older activists is not synonymous with drawing divisions, as the older activists understood the assets that students solely possessed to further the movement along. In fact, many of the older activists encouraged the younger activists and actively supported them in numerous ways.

For example, when Bennett College students, who were the heroines on the 1963 Greensboro protests, were arrested and refused bail during the 1963 sit-ins in Greensboro, their professors came to the jail facilities and gave them their classroom and homework assignments every week. This scenario personifies the symbiotic relationship between both generations in the fight against racism, as the professors showed their appreciation for the young people’s unique and valiant position for the benefit of the entire race and future generations, yet not removing the students from their responsibilities and academic requirements.

Altogether, students endured countless hardships that included incarceration, verbal assaults and physical violence. Sometimes, attacks from white antagonists were compounded by disproportionate responses from law enforcement, as Portsmouth activist, Edward Rodman explained, “…the fire department, all of the police force and police dogs were mobilized. The police turned the dogs loose on the Negroes-but not all the whites.”

Students also understood that they could pay the ultimate price for protesting against the status quo of racial inequality, as numerous activists were murdered throughout the Civil Rights era. Nevertheless, over 50,000 black students and sympathizers participated in the sit-ins of 1960. As historian Clayborne Carson highlighted, “Nonviolent tactics, particularly when accompanied by rationale based on Christian principles, offered black students…a sense of moral superiority, an emotional release through militancy, and a possibility of achieving desegregation.”

A movement within a movement was born on February 1, 1960 and that movement evolved into its own distinct force by the middle of the decade. Soon after the sit-ins began, students realized their collective prowess, as student activism consistently helped define the decade of the 60s in forcing monumental political, legal and social changes throughout the nation.

Finally, the black student activists of the 1960 sit-ins did three important things, albeit unintentional: they helped lay the foundation for all collective student activism in the 60s and beyond, they played a legendary role in the larger African-American Freedom Movement that began as early as Africans’ arrival to colonial America, and they cemented a valuable place in one of America’s most significant traditions, the protest tradition, which has continuously defined and propelled our country since its inception.

Our society, and all post-1960 social movements, have undeniably benefited from the audacity of those four brave freshmen and their actions on February 1, 1960.

Dr. Kelton Edmonds is a Professor of History at California University of Pennsylvania. His primary research is on Black Student Activism in the United States. He is a native of Portsmouth, VA and graduated from I.C. Norcom High school in 1993. He holds B.A. and M.A. degrees in Secondary Education-History from North Carolina A&T State University. He earned his Ph.D. in 20th Century US History from the University of Missouri-Columbia.

#NNPA BlackPress

Black Troops Fought Bravely at Normandy 75 Years Ago

NNPA NEWSWIRE — Throughout WWII and especially D-Day in 1944, the Black Press dispatched reporters such as the New Journal and Guide’s John Q. ‘Rover’ Jordan, P.B. Young, Jr., Thomas Young, Lem Graves and the ANP’s Joseph Dunbar to the European and South Pacific War Zones to cover the exploits of the Black soldiers.

By Leonard E. Colvin, Chief Reporter, New Journal and Guide

The United States, Great Britain, France and other allies recently observed the 75th anniversary of the D-Day landing on five beaches along Southern France at Normandy on their way to defeat Nazi Germany.

The modern images of the allied leaders, including the U.S. President and other participants, captured by the media at the Normandy Beach event appeared mostly white.

Seventy-five years ago, the mainstream news media and various movies such as “The Longest Day” and others also captured the images of white soldiers valiantly fighting on the sandy beaches against withering gunand cannon fire from the Germans.

But thanks to the written words and imagesrecorded by members of the Black Press who were eye witnesses to the action in Southern France to Berlin, the contributions and valor of Black military men and women were recorded, too.

Along with a quarter million Black servicemen, Black newsmen from the Norfolk Journal and Guide, the National Newspaper Publisher’s Association (NNPA)and the Associated Negro Press (ANP) were on hand to recordthis history left out of the mainstream press then and recently.

Throughout WWII and especially D-Day in 1944, the Black Press dispatched reporters such as the New Journal and Guide’s John Q. ‘Rover’ Jordan and P.B.Young, Jr.,Thomas Young, Lem Graves and the ANP’s Joseph Dunbar tothe European and South Pacific War Zones to cover the exploits of the Black soldiers.

In many of the stories printed on the pages of the GUIDE, one could detect the toneof the accounts indicating that the reporters wanted to make clear that “Negro” soldierswere making significant contributions.

They worked on the ground and the air in combat, in support roles like driving trucks, operating machinery,medical support units, military police, tactical and leading administrative work.

The tone countered the daily newspapers which catered to its white readership, ignoring any significant contributions of the Black Warriors.

“If it were not for those GUIDE and other Black reporters, the story of Black men and women on D-Day or in other areas related to World War II would have beenignored,” said Dr. Henry Lewis Suggs, Professor Emeritus of American History, Clemson University, who is retired now.

Dr. Suggs wrote the biography “P.B. Young, Sr., Newspaper Man.” Young, who founded the GUIDE newspaper after serving as the editor of its predecessor, the Lodge Journal newsletter dating to 1900, was a leading Black media,political and civic leader in Virginia and nationally from the early 1930s until he died in 1962.

Weekly, during the war, the GUIDE published local,state, national, Virginia and Peninsula editions of the newspaper. Each edition included news about the war and the rolesthat Black soldiers, sailors, Coast Guard and civilians played at home and abroad.

The articles not only pointed out the bravery and professionalism of the Black troops, they also noted the heavy number of casualties Blacks suffered in combat.

The stories which were distributed to other Black newspapers also recorded acts of racial bias against the Black patriots.

There were stories of the many cases where Black and white troops worked “shoulder to shoulder” withno tension away from the field of battle and during it.

“In Norfolk, the only source of news Black civilians got about Black soldiers and sailors overseas or at home was from the Black Press,” said Suggs.

Suggs said the contributions of the Black warriors during WWII helped fuel African American efforts after the war to pursue socio-economic and political equality.

Further, the thousands of Blacks who fought in the war, used the G.I. Bill to secure an education and other support to attend Black colleges which helped them grow.

Suggs said that African Americans had their great generation of Black men who participated in the war. They later became the Black lawyers, doctors and educators and other professional and political class whofostered the Black middle class.

“Negro troops did their duty excellently under fire on Normandy’s beaches in a zone of heavy combat,” General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Commander of the Allied Invasion Forces, declared.

That statement was a greeting sent by the General, fondly known as “Ike” by the Black troops, to the NAACP’sWartime Conference meeting In Chicago held that year. It appeared in the July 15, 1944 edition of the GUIDE under the headline “Eisenhower Proud of Our Troops in France,” verifying history.

It also noted Black leadership’s citing the resistance and their insistance for sending Black Women Army Corps (WACs) to the front.

“Negro” troops in Southern France. Photo by John Q. Jordan/NJG Archives

John Q. Jordan, War Correspondent

John Q. Jordan, who lived in Portsmouth, worked for the GUIDE as a correspondent before, during and after the crucial landing at Normandy and observed firsthand the activities of Black soldiers.

He also served as a pool reporter, recording and dispatching back bits and pieces of information for white and Black reporters toiling for news outlets sitting onboard ships or on land in England, the main staging areas for the massive invasion force.

During the first hours of operations on the Omaha Beach, Jordan was one of the first journalists to view the action.

He was positioned to peer down at 800-plus of ships sitting or moving in the waters below and the troops scrambling to the beaches.

In an article in the August 19, 1944 edition of the GUIDE, under the headline “Germans Only Attack Negro Group Invasion Day; Rhodes Gets One,” he described those hours of operation.

Jordan wrote,“Many Negro troop units land on Beaches; Fliers handling the role in softening up second Invasion coast.”

He described how on D-Day (June 6) weeks after, “Theonly fighter opposition (the Germans) encountered by the formations which flew protective cover for the Armada of heavies (bombers)and medium bombers who blasted a path for the invasion…on the coast of southern France was met by fighter pilots of the Mustang Group under (the command of) Col. Benjamin O. Davis Jr.,” an African American.

Better known as the Tuskegee Airmen, the article described how 2nd Lt.George M. Rhodes of Brooklyn, New York shot down a German plane —the first.

The Black men who manned and operated the huge machines hailed from all over the country, including Little Rock, Arkansas, parts of Texas, and Philly.

“They have been in operations over the whole length of the beach since D-day. These units were formed in Camp Gordon Johnson, Fla. and the first colored company of its type.”

These amphibious ships were used to transport troops and supplies back and forth from the beaches,including taking wounded Black and white men to the awaiting hospital ships.

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoLIHEAP Funds Released After Weeks of Delay as States and the District Rush to Protect Households from the Cold

-

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of November 26 – December 2, 2025

-

Alameda County3 weeks ago

Alameda County3 weeks agoSeth Curry Makes Impressive Debut with the Golden State Warriors

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoSeven Steps to Help Your Child Build Meaningful Connections

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoSeven Steps to Help Your Child Build Meaningful Connections

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoTrinidad and Tobago – Prime Minister Confirms U.S. Marines Working on Tobago Radar System

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoThanksgiving Celebrated Across the Tri-State

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoTeens Reject Today’s News as Trump Intensifies His Assault on the Press