Art

REVIEW: Ishmael Reed’s Play “The Slave Who Loved Caviar,” Comments on Black Artists and White Sponsors

[Haitian-Puerto Rican American artist, Jean-Michel] Basquiat rose to fame in the neo-expressionist art movement in the 1980s and [Andy] Warhol, one of his mentors, had gained renown for Pop Art and drug use in the 1960s. They died within a year of each other, Warhol at age 59 in 1987 and Basquiat died of an overdose at age 27 in 1988.

By Wanda Sabir

Ishmael Reed’s current play, directed by Carla Blank, “The Slave Who Loved Caviar,” at Theater for the New City until January 9, explores Black culture and white exploitation in the relationship between the Haitian-Puerto Rican American artist, Jean-Michel Basquiat and Andy Warhol.

Basquiat rose to fame in the neo-expressionist art movement in the 1980s and Warhol, one of his mentors, had gained renown for Pop Art and drug use in the 1960s. They died within a year of each other, Warhol at age 59 in 1987 and Basquiat died of an overdose at age 27 in 1988.

There are so many analogous parallels, both fictional or mythic and actual that it is amazing that the play only has one intermission.

In his play, Reed postulates that the older, white artist presented himself as a benevolent father figure. While under the influence of drugs, a willing Basquiat allows Warhol to install him in a basement where Basquiat churns out art like an assembly worker.

Reed’s premise here is that Warhol had gotten away with a crime.

The cold case is reopened by two forensic scientists, Grace and Raksha, (Monisha Shiva and understudy Kenya Wilson) who want to bring the perpetrators to justice. As the contemporary team investigates, time shifts back and forth as what happened to Basquiat had perpetuated with other captives.

Slave owners used cocaine — which Basquiat used excessively — to increase productivity among the captives, Reed says. Just as slavery was once legal, the Warhol machine also had legal protection, money and power.

Reed’s writing is crisp and sharp as are the actors who deliver and deliver and deliver some more. Carla Blank’s direction is also on point as the diction and storylines unfold clearly in nuanced layers.

I love the scene in Act 2 where the ghost of Richard Pryor — appearing as a shadow puppet danced by actor, Kenya Wilson — tries to prevent Basquiat from going up in chemical flames like the late comedian had.

Pryor’s ghost speaks to the art of selling out to Hollywood, another type of killing field for Black art and artists. We sense Pryor’s regret that he didn’t stay with people who loved him. It’s hard to tell friend from foe when engulfed in f(l)ame(s).

Reed’s characters also convey the prevailing attitudes by police that allow the wealthy and famous to get away with everything from theft to murder, a very real problem on and off the page.

Roz Fox’s Detective Mary van Helsing is a cool sleuth who goes looking for the missing appetizer, “Jennifer Blue” (actor Kenya Wilson) despite legal disinterest. She is our hero. Don’t worry, this is a spoiler, but there is so much going on here, you will probably forget I told you.

In “Slave” we see too often how historians are propagandists who lie to keep the empire solvent.

Remember Orwell’s Ministry of Truth in “1984”? I am reminded also of Jimi Hendrix (1970) and his demise—yes to a drug overdose. . . Fuquan Johnson (2021), Shock G (2021), Juice WRLD (2020), Billie Holiday (1959), Whitney Houston (2012), The Artist Formerly Known as Prince (2006), Michael Jackson (2009).

Since it is Ishmael Reed, we can actually have a happy ending.

The late bell hooks wrote in “Outlaw Culture: ‘Altars of Sacrifice: “Re-membering Basquiat’,” that the young, yet masterful artist “journeyed into the heart of whiteness.

White territory he named as a savage and brutal place. The journey is embarked upon with no certainty of return. Nor is there any way to know what you will find or who you will be at journey’s end. . . . Basquiat understood that he was risking his life—that this journey was all about sacrifice [. . .]” (36). this and his refusal to allow the dominant culture to tell our story, the 99%, the percentage who matter.

How difficult it must have been for the artist to have his say as he dangled from a purveyor’s noose. Herein lies Black genius. Herein lies the tragedy. Ishmael Reed’s ability to cultivate success for the past 60 or so years stems from his artistic eReed’s research is impeccable—I lose track of some of the names, like the artist who boycotts with other Black artists a museum that sets out to exploit them.

Reed is certainly prescient as is the Theater for The New City’s Artistic Director Crystal Field. As confederate monuments are toppled throughout the nation and reparations are a very real possibility, “The Slave Who Loved Caviar” certainly sets a precedent. “Slave” is a challenge and a wakeup call to those who have not been paying attention to the right thing. “Slave” says, change the channel. What did the Last Poets say about the Revolution?

The play is streaming through Jan. 9, 2022, at Theater for the New City. Streaming tickets are just $10+ small fee. For in person ($15.00) and virtual tickets visit https://ci.ovationtix.com/35441/production/1091241

You can learn more about Reed on my radio or podcast interview here.

We had a conversation with many members of the cast January 5, 2022 on Wanda’s Picks Radio Show podcast. Tune in (subscribe): http://tobtr.com/12046944

Activism

‘I Was There Too’ Reveals the Hopes, Dangers of Growing Up in The Black Panther Party

On July 20, at the Oakland Museum of California’s Spotlight Sundays, Gabriel, the daughter of a Black Panther Party couple, Emory Douglas, minister of culture, and artist-educator, Gayle Asalu Dickson, gave a raw personal view of being raised in the middle of the Black Power Movement.

By Carla Thomas

Chronicles of the Black Panther Party are often shared from the perspectives of Huey Newton, Bobby Seale, Angela Davis, or Kathleen Cleaver. However, the view from a Panther’s child was unique on stage as Meres-Sia Gabriel performed, “I Was There Too.”

On July 20, at the Oakland Museum of California’s Spotlight Sundays, Gabriel, the daughter of a Black Panther Party couple, Emory Douglas, minister of culture, and artist-educator, Gayle Asalu Dickson, gave a raw personal view of being raised in the middle of the Black Power Movement.

Gabriel took the audience on her tumultuous journey of revolution as a child caught between her mother’s anger and her father’s silence as the Party and Movement were undermined by its enemies like the COINTELPRO and the CIA.

Gabriel remembers her mom receiving threats as the Party unraveled and the more lighthearted moments as a student at the Black Panther Party’s Community School.

The school was a sanctuary where she could see Black power and excellence in action.

It was there that she and other children were served at the complimentary breakfast program and had a front row seat to the organization’s social and racial justice mission, and self-determination, along with the 10-point platform where the party fought for equality and demanded its right to protect its community from police brutality.

On her journey of self-development, Gabriel recounted her college life adventures and transformation while immersed in French culture. While watching television in France, she discovered that her father had become a powerful post-revolution celebrity, sharing how high school and college-age youth led a movement that inspired the world.

Through family photographs, historical images projected on screen, personal narratives, and poetry, Gabriel presented accounts worth contemplating about the sacrifices made by Black Panther Party members. Her performance was backed by a jazz trio with musical director Dr. Yafeu Tyhimba on bass, Sam Gonzalez on drums, and pianist Sam Reid.

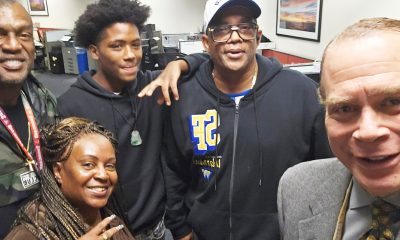

At the Oakland Museum of California, Amy Tharpe, Ayanna Reed, artist Meres-Sia Gabriel and Kenan Jones at the meet-and-greet after the “I Was There Too” multimedia production. Photo by Carla Thomas.

Gabriel’s poetry is featured in the “Black Power” installation at the Oakland Museum of California, and her father’s book, “Black Panther: The Revolutionary Art of Emory Douglas,” features her foreword. She accompanied her father on tour exhibiting his artwork from the Panther Party’s publication as Minister of Culture.

Gabriel considers her work as a writer and performer a pathway toward self-reflection and personal healing. While creating “I Was There Too,” she worked for a year with the production’s director, Ajuana Black.

“As director, I had the opportunity to witness, to create, to hold space with tenderness and trust,” said Black. “Her performance touched my soul in a way that left me breathless.”

With over two decades of musical theater experience, Black has starred in productions such as “Dreamgirls” as Lorrell and “Ain’t Misbehavin’s” Charlene. She also performs as the lead vocalist with top-tier cover bands in the Bay Area.

During the post-performance meet-and-greet in the (OMCA) Oakland Museum of California garden, Gabriel’s father posed for photos with family and friends.

“I am proud of her and her ability to share her truth,” he said. “She has a gift and she’s sharing it with the world.”

Shona Pratt, the daughter of the late BPP member Geronimo Pratt, also attended to support Gabriel. Pratt and Gabriel, known as Panther Cubs (children of the Black Panther Party), shared their experience on a panel in Richmond last year.

“Meres-Sia did a great job today,” said Pratt. “It was very powerful.”

Meres-Sia Gabriel was born and raised in Oakland, California. A graduate of Howard University in Washington, D.C., and Middlebury College School in France, Gabriel serves as a French instructor and writing coach.

Activism

The Past and Future of Hip Hop Blend in Festival at S.F.’s Midway

“The Music and AI: Ethics at the Crossroads” panel featured X.Eyee, CEO of Malo Santo and senior advisor for UC Berkeley’s AI Policy, Sean Kantrowitz, director of media and content @Will.I.A.’s FYI, Adisa Banjoko of 64 Blocks and Bishop Chronicles podcast, and Julie Wenah, chairwoman of the Digital Civil Rights Coalition.

By Carla Thomas

“Cultural Renaissance,” the first-ever SF Hip-Hop conference, occurred at The Midway at 900 Marin St. in San Francisco on July 18 and 19. Held across three stages, the event featured outdoor and indoor performance spaces, and a powerful lineup of hip-hop icons and rising artists.

Entertainment included Tha Dogg Pound, celebrating their 30th anniversary, Souls of Mischief, and Digable Planets. “Our organization was founded to preserve and celebrate the rich legacy of Hip-Hop culture while bringing the community together,” said SF Hip-Hop Founder Kamel Jacot-Bell.

“It’s important for us to bring together artists, innovators, and thought leaders to discuss how hip-hop culture can lead the next wave of technological and creative transformation,” said Good Trouble Ventures CEO Monica Pool-Knox with her co-founders, AJ Thomas and Kat Steinmetz.

From art activations to cultural conversations, the two-day event blended the intersections of AI and music. Panels included “Creative Alchemy – The Rise of the One-Day Record Label,” featuring producer OmMas Keith, composer-producer Rob Lewis, AI architect-comedian Willonious Hatcher, and moderator-event sponsor, AJ Thomas.

“The Legends of Hip-Hop and the New Tech Frontier” panel discussion featured hip-hop icon Rakim, radio personality Sway, chief revenue officer of @gamma, Reza Hariri, and music producer Divine. Rakim shared insights on culture, creativity, and his A.I. start-up NOTES.

“AI is only as good as the person using it,” said Rakim. “It cannot take the place of people.”

Rakim also shared how fellow artist Willonious helped him get comfortable with AI and its power. Rakim says he then shared his newfound tool of creativity with business partner Divine.

The panel, moderated by the Bay Area’s hip-hop expert Davey D, allowed Divine to speak about the music and the community built by hip-hop.

“Davey D mentored me at a time when I had no hope,” said Divine. “Without his support, I would not be here on a panel with Rakim and Willonious.”

Hatcher shared how his AI-produced BBL Drizzy video garnered millions of views and led to him becoming one of Time magazine’s 100 most influential AI creators.

“The Music and AI: Ethics at the Crossroads” panel featured X.Eyee, CEO of Malo Santo and senior advisor for UC Berkeley’s AI Policy, Sean Kantrowitz, director of media and content @Will.I.A.’s FYI, Adisa Banjoko of 64 Blocks and Bishop Chronicles podcast, and Julie Wenah, chairwoman of the Digital Civil Rights Coalition.

“Diverse teams solve important questions such as: ‘How do we make sure we bring diverse people to the table, with diverse backgrounds and diverse lived experiences, and work together to create a more culturally sound product,’” said Wenah.

Self-taught developer, X.Eyee said, “You have to learn the way you learn so you can teach yourself anything. Future jobs will not be one roadmap to one individual skill; you will be the orchestrator of teams comprised of real and synthetic humans to execute a task.”

Activist Jamal Ibn Mumia, the son of political prisoner Mumia Abu Jamal, greeted Black Panther Party illustrator Emory Douglas, who was honored for his participation in the Black Power Movement. Douglas was presented with a statue of a black fist symbolizing the era.

“It’s an honor to be here and accept this high honor on behalf of the Black Panther Party,” said Douglas, holding the Black Power sculpture. “It’s an art (my illustrations) that’s been talked about. It’s not a ‘me’ art, but a ‘we’ art. It’s a reflection of the context of what was taking place at the time that inspired people.

“To be inspired by is to be in spirit with, to be in spirit with is to be inspired by, and to see young people continue on in the spirit of being inspired by is a very constructive and powerful statement in the way they communicate,” Douglas said.

His work embodied the soul of the Black Panther Party, and as its minister of culture and revolutionary artist, he definitely keeps the Panther Party soul alive, and his work is everywhere.

“Brother Emory Douglas is an icon in the community,” said JR Valrey of the Block Report.

“Fifty years later, he’s still standing,” said Ibn Mumia, raising his fist in the traditional Black Power salute.

“Emory is a living legend and so deserving of this award,” Valrey said. “We have to honor our elders.”

Activism

Mayor Lee’s Economic Development Summit at Oakstop Furthers Creative Strategies for Oakland’s Future

Oakstop’s workforce development initiative, “The Oakstop Effect: WFD,” focuses on providing pathways to employment and advancement for Black adults aged 18–64. Through culturally relevant, mission-driven training facilitated by Black professionals with relatable backgrounds, the program creates supportive environments for skill-building, wealth creation, and worker empowerment.

By Carla Thomas

On Monday, Aug. 4, Oakland Mayor Barbara Lee convened the Mayor’s Economic Development Working Group at Oakstop, drawing leaders from business, workforce development, arts and culture, education, small business, and community organizations.

This initiative builds on the administration’s deep-rooted community engagement efforts, expanding on the dozens of roundtables and listening sessions conducted during Lee’s first 76 days in office.

The collaborative session aimed to shape an economic strategy rooted in equity, creativity, and community using the mayor’s five-point economic plan, including empowering small businesses, strengthening the local workforce, revitalizing Oakland’s cultural and social landscape, attracting and retaining strategic sectors, and ensuring economic opportunity for all communities.

During breakout sessions, participants shared recommendations across five focus areas: economic policy, small business support, workforce development, narrative change, and integration of arts and culture.

More than 100 participants at the meeting, which included former Alameda County Supervisor Keith Carson, Black Cultural Zone CEO Carolyn Johnson, East Oakland Youth Development Center CEO Selena Wilson, African American Sports and Entertainment Group founder, Ray Bobbitt, Executive Director of the Oakland School for the Arts Mike Oz, Visit Oakland Executive Director Peter Gamez and activist-artist Kev Choice.

“Our economic development working group aims to spark collaboration, uplift existing successes, and identify what’s needed to keep The Town open for business — vibrant, safe, and rooted in equity,” said Lee remarked at the gathering.

Oakstop founder and CEO Trevor Parham stated that the summit felt like an open community forum. “It’s critical to have as many perspectives as possible to drive solutions so we can cover not only our concerns, but fulfill our economic mission,” said Parham.

Parham says the community should expect summits and collaborations more often at Oakstop. “I’m excited about the prospects and the outcomes from bringing people from different industry sectors as well as different levels.”

Oakstop’s workforce development initiative, “The Oakstop Effect: WFD,” focuses on providing pathways to employment and advancement for Black adults aged 18–64. Through culturally relevant, mission-driven training facilitated by Black professionals with relatable backgrounds, the program creates supportive environments for skill-building, wealth creation, and worker empowerment.

“Our goal is to foster worker power for local workers, to build wealth, while building skills and redefining the workplace,” said Parham.

The program is powered through partnerships with organizations such as Philanthropic Ventures Foundation and Community Vision. Beyond workforce development, Oakstop offers co-working spaces, event venues, art galleries, and mental health and wellness programs — reinforcing its mission of community empowerment and economic mobility.

With a strategic equity framework, cultural and economic integration, and a continuous pipeline of sustainable talent, Lee plans to revitalize the Oakland economy by creating policies and opportunities that stabilize the city.

-

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks agoDesmond Gumbs — Visionary Founder, Mentor, and Builder of Opportunity

-

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks agoFamilies Across the U.S. Are Facing an ‘Affordability Crisis,’ Says United Way Bay Area

-

Alameda County4 weeks ago

Alameda County4 weeks agoOakland Council Expands Citywide Security Cameras Despite Major Opposition

-

Alameda County4 weeks ago

Alameda County4 weeks agoBling It On: Holiday Lights Brighten Dark Nights All Around the Bay

-

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks agoBlack Arts Movement Business District Named New Cultural District in California

-

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks agoLu Lu’s House is Not Just Toying Around with the Community

-

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of December 17 – 23, 2025

-

Black History3 weeks ago

Black History3 weeks agoAlfred Cralle: Inventor of the Ice Cream Scoop