Community

The Philadelphia Masjid, Inc.: Reclaiming a bastion for Black Muslims

THE PHILADELPHIA TRIBUNE — As one of the nation’s most historic Islamic sites, The Philadelphia Masjid, Inc. has a deep and textured history that’s seen highs and lows — from the building of a thriving religious community to having its very existence threatened. The Masjid was established in 1976 as a congregation of eight temples that were formerly apart of the Nation of Islam, and is known for fostering a robust Black Muslim community that produced devout followers, operated businesses and maintained an independent school.

#NNPA BlackPress

COMMENTARY: Women of Color Shape Our Past and Future

MINNESOTA SPOKESMAN RECORDER — Every March, Women’s History Month invites us to pause and honor the women whose courage, intellect, and leadership have shaped our world. This year, that invitation feels especially urgent. We are living in a time when history is being rewritten, when DEI is being recast as a threat, and when the stories we choose to uplift matter more than ever. The stories of women of color must be centered, celebrated, and carried forward with intention.

#NNPA BlackPress

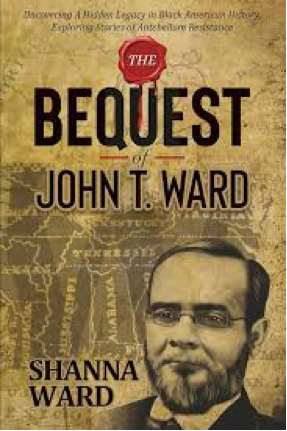

Woman’s Search for Family’s Roots Leads to Ancestor John T. Ward – A Successful Entrepreneur and Conductor on the Underground Railroad

THE AFRO — For years, she wanted to know more about her ancestor John T. Ward, she said, and her curiosity eventually became an obsession, leading her to become the genealogist for her family. And so, for more than a decade, she set out to trace her family’s roots and discovered a story that would change her life and the way she viewed American history.

#NNPA BlackPress

Advocates Raise Alarm Over ICE Operation, MOU and Detention Risks in Baltimore County

THE AFRO — “This is highly problematic given many of the charges that land people in county correctional facilities to begin with are for misdemeanors of which they may not even ultimately be proven guilty and convicted,” said Cathryn Ann Paul Jackson, public policy director for We Are CASA. “It results in a subversion of the local criminal justice system as a means to further racial profiling and do ICE’s dirty work.”

-

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks agoCommunity Celebrates Turner Group Construction Company as Collins Drive Becomes Turner Group Drive

-

Business4 weeks ago

Business4 weeks agoCalifornia Launches Study on Mileage Tax to Potentially Replace Gas Tax as Republicans Push Back

-

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks agoDiscrimination in City Contracts

-

Arts and Culture4 weeks ago

Arts and Culture4 weeks agoBook Review: Books on Black History and Black Life for Kids

-

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks agoCOMMENTARY: The Biases We Don’t See — Preventing AI-Driven Inequality in Health Care

-

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks agoPost Newspaper Invites NNPA to Join Nationwide Probate Reform Initiative

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoCOMMENTARY: The National Protest Must Be Accompanied with Our Votes

-

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks agoNew Bill, the RIDER Safety Act, Would Support Transit Ambassadors and Safety on Public Transit