Black History

The Spectacular Find of the Clotilda and What’s Next

THE BIRMINGHAM TIMES — The discovery of the Clotilda slave ship last month in the Mobile River Delta is one of the rarest of archaeological artifacts: tangible evidence validating the story that Africans had been forcefully ripped from their homelands. Because it was the last documented vessel known to have brought enslaved people to America, specifically to Alabama and to Mobile, the Alabama Historical Commission (AHC) had a duty to find the last known slave ship that transported kidnapped men, women, and children from Africa to Alabama.

By Vickii Howell

MOBILE, Ala.—The discovery of the Clotilda slave ship last month in the Mobile River Delta is one of the rarest of archaeological artifacts: tangible evidence validating the story that Africans had been forcefully ripped from their homelands. Because it was the last documented vessel known to have brought enslaved people to America, specifically to Alabama and to Mobile, the Alabama Historical Commission (AHC) had a duty to find the last known slave ship that transported kidnapped men, women, and children from Africa to Alabama.

Under the federal mandate set forth in the Abandoned Shipwrecks Act of 1999, the AHC, the State Historic Preservation Office of Alabama, is charged with the management and guardianship of maritime archaeological sites abandoned and embedded in Alabama waters, according to its press release.

Now, it is the AHC’s job to protect and preserve the remains of the Clotilda. The AHC and its adjunct, the Black Heritage Council, are also tasked with interpreting history as it really was from the viewpoint of the slaves and their descendants in Africatown, located three miles north of downtown Mobile, which had been formed by a group of 32 West Africans, who in 1860 were part of the last known illegal cargo of slaves to the United States.

The AHC will work closely with Africatown to make sure the community’s history is interpreted and that it directly benefits from the Clotilda find, said Clara Nobles, AHC Assistant Executive Director.

Nobles spoke to the Birmingham Times about the spectacular find and what happens next.

The Birmingham Times: You guys have been sitting on this news for a long time. What does it feel like to finally let this story out? And what does this mean for you not only as a key person with the AHC but also as an African American?

Nobles: Well, it means we just celebrated our big “Wow!” We have been working on this story for almost two years in partnership, of course, with Ben Raines, [formerly of AL.com], who brought attention to the Clotilda. We did a lot of work on it … [and] realized it was not the Clotilda [that he discovered]. Being energized, we were able to continue the search and eventually come upon the ship that we now know as the Clotilda. So, this has been a long road, and not just for the AHC. [It’s] certainly been a much longer road for the people of Africatown, for the city of Mobile, for the city of Prichard, for Alabama, and also for the nation. Yes, so we do a big sigh of relief, and say, “Thank you, Jesus, that we have gotten the ship!”

Now, the whole thing is, what comes next now that we’ve got this? … I understand that this artifact, this ship in the water, is very important. But … I look to the people for the story. I think we have to go back and be able to get all of this story and to tell this story. As it’s been said already, … we [are] a strong people with resilience and tenacity—people taken from their homeland against their will and brought to this country, people who [still were] able to strive and survive. For me, I just feel proud. I’m not a direct descendant, but I am an African American, so I feel proud to be here today and humble more than anything else.

BT: As far as the AHC, what are the plans for your next steps?

The Alabama Historical Commission announces that the Clotilda has been officially discovered in Mobile Bay.Thursday. May 30, 2019 – Event Photography by Keith Necaise

Nobles: Well, one of the next things we did was release the science [on May 30], so that information is out in the public domain. In that science were recommendations for going forward. One of the things, as a historic commission, we are concerned with is the protection of the ship. That’s our first priority: to make sure the ship is secure. What we will be doing, hopefully, is pairing in the future with the National Geographic Society again to probably do some further excavation on the ship; to see how much of it is in the mud, its condition; … to see if there are some artifacts, things we could potentially bring up. That would be an immediate next step after things have cooled down a little bit.

BT: Now that you’ve gotten the scientific data, what will it take to bring it up? Or will you leave it where it is?

Nobles: The science will dictate what we can do. The ship isn’t in great condition, [at least not] the part they can see. We knew it was burned. We knew it was dynamited. [Everything is now] going on with the part that is visible, the part we can see and feel. But we don’t know the condition of what’s under the mud. All of that will dictate what we do with the ship. But I will tell you, conservation is very, very, very expensive. We will need millions and millions of dollars if we bring up, much less conserve, anything. So, instead of putting that money into conserving something that’s going to be shards and pieces, we might look to do something else in Africatown that would be more of a memorial or a replica. State Senator [Vivian] Figures (D-Mobile) spoke about a potential replica.

As you’ve heard, AHC Executive Director Lisa Jones and I have been in Washington, D.C., several times talking to Congressman [Bradley] Byrne (R-Mobile) about what we can do on a national level, not just on the local and state level. This is also an international story, so the whole nation needs to get behind the story and give it a gigantic push. We were talking to [Byrne] about potentially, when we are finished with the excavation of the ship, doing some kind of memorial on the water, and the memorial will lead visitors to Africatown.

BT: We also heard about protection. Did I hear [someone] mention that there would be severe consequences if anyone tried to meddle with the ship?

Nobles: Absolutely. We have been working in conjunction with the governor’s office, the Alabama Department of Conservation, the Alabama Law Enforcement Agency (ALEA), and the attorneys general of Alabama, Mobile County, and Baldwin County. They are putting out a press release warning people that anybody who tries to do anything to that ship will be prosecuted to the very [maximum extent] of the law. It’s a Class C felony to tamper with that ship.

BT: What role will descendants play in what happens with the ship?

Nobles: We will be in constant communication and meetings with the descendants because they need to be on top of that. We will talk with them so we can understand their vision for the community. We’ve got to get a vision before we can do anything because without a vision the people perish. We understand that we have to get them engaged because this is not just our story to tell. We’re not going to be the state government coming in here telling Africatown what to do. We want to be in partnership with them, to offer them help, to have them to tell us what a good idea is. Before we build anything, we’ve got to have a master plan. We’ve got to have a plan, so we know where we’re going and what we’re doing.

BT: You are working with the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture and the Slave Wrecks Project in Washington, D.C., about preserving the ship. Is there any discussion about taking it to the National Mall?

Nobles: We will definitely make sure it stays in Africatown. We will lay our bodies down on that ship before letting it leave Alabama, so it will not be taken away. I will say this, if we bring up artifacts that need to be conserved before we have a museum, then we will ask the Smithsonian to curate those things, but then they would come back to Africatown.

BT: There was some talk about taking the ship to the GulfQuest Maritime Museum …

Nobles: No.

BT: … about the ship ending up downtown Mobile …

Nobles: No, we would not do that. We would not be in favor of that. If there’s something that can be brought up, we will likely get that curated, but it will come back to Africatown. When we build whatever, it’s coming back.

BT: If a museum were to open one day, what do you think the economic impact would be on Africatown?

Nobles: I think it would be tremendous because this is going to be not just a national story or a state story but an international story. We have experienced an international, large overflow of tourism in Montgomery because of the Equal Justice Initiative’s [National Memorial for Peace and Justice, known as the National Lynching Memorial]. The tourism dollars will come as people will come.

They will not only come to visit the museum: they will stay overnight, they have to eat, they have to sleep in hotels. So, the area will need hotels, restaurants, nice stores, boutiques, shops, visitor’s centers, tour guides, gas stations, grocery stores—all those things will boost the economy.

BT: What do you think the economic impact of the Clotilda find will have on the lives of people in Africatown in terms of dollars and cents?

Nobles: Oh, my gosh! People will want to come here not only to visit but also to live. This plan for Africatown, the museum, or whatever we do here, I just hope everyone understands that it’s not going to happen overnight. This is a long-range planning process, and it will take a couple of steps. We will get there, if we all stick together.

This article originally appeared in The Birmingham Times.

Activism

Oakland Post: Week of April 23 – 29, 2025

The printed Weekly Edition of the Oakland Post: Week of April 23 – 29, 2025

To enlarge your view of this issue, use the slider, magnifying glass icon or full page icon in the lower right corner of the browser window.

Activism

Oakland Post: Week of April 16 – 22, 2025

The printed Weekly Edition of the Oakland Post: Week of April 16 – 22, 2025

To enlarge your view of this issue, use the slider, magnifying glass icon or full page icon in the lower right corner of the browser window.

Activism

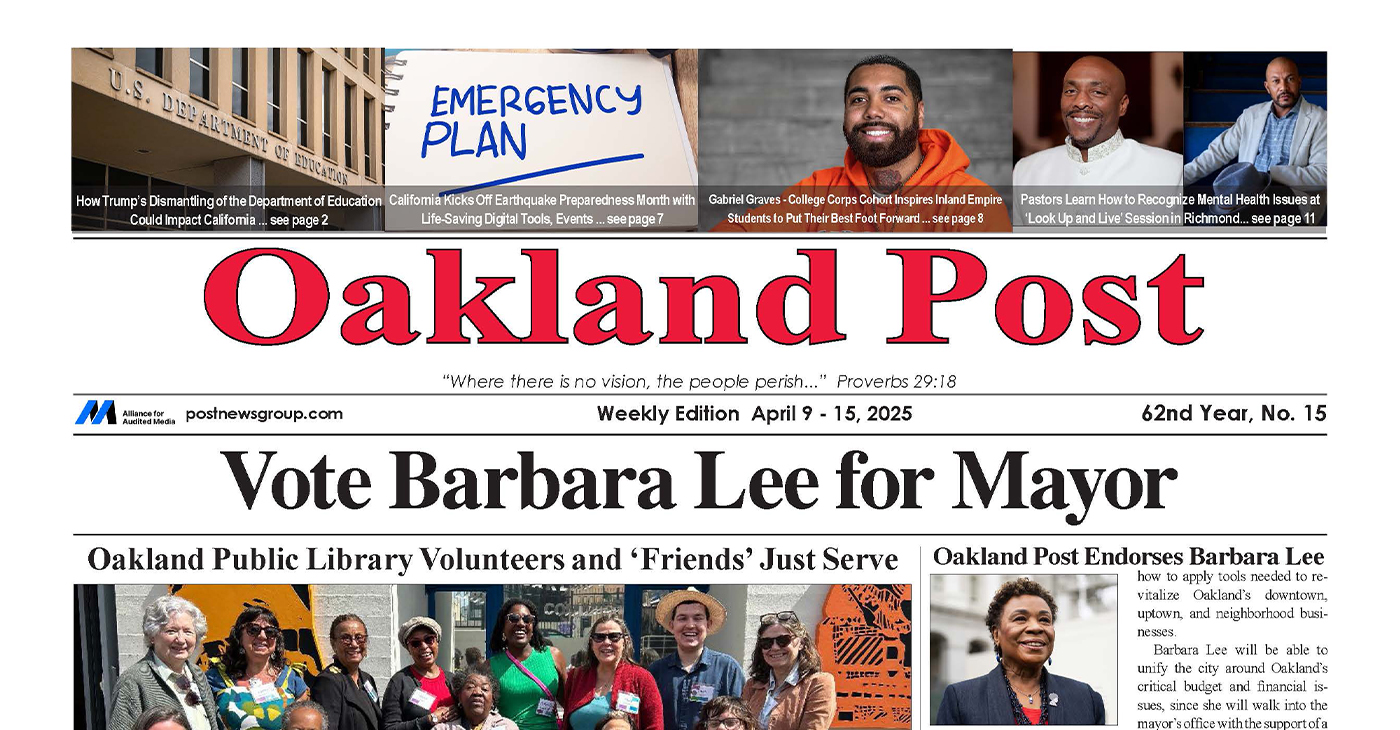

Oakland Post: Week of April 9 – 15, 2025

The printed Weekly Edition of the Oakland Post: Week of April 9 – 15, 2025

To enlarge your view of this issue, use the slider, magnifying glass icon or full page icon in the lower right corner of the browser window.

-

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks agoOakland Post Endorses Barbara Lee

-

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of March 28 – April 1, 2025

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of April 2 – 8, 2025

-

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks agoTrump Profits, Black America Pays the Price

-

Activism2 weeks ago

Activism2 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of April 9 – 15, 2025

-

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks agoHarriet Tubman Scrubbed; DEI Dismantled

-

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks agoLawmakers Greenlight Reparations Study for Descendants of Enslaved Marylanders

-

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks agoTrump Targets a Slavery Removal from the National Museum of African-American History and Culture