Black History

Times change, but the objective of the demonstrations shouldn’t

THE BIRMINGHAM TIMES — Civil Rights Movement tactics may change, but the objectives shouldn’t.

By Ameera Steward

Civil Rights Movement tactics may change, but the objectives shouldn’t, said Doris Gary, 85, who participated in the marches of the 1960s and lived in Collegeville when the Rev. Fred L. Shuttlesworth was pastor of historic Bethel Baptist Church.

[/media-credit] Doris Gary participated in the marches in the ’60s and lived in Collegeville when the Rev. Fred L. Shuttlesworth was pastor of historic Bethel Baptist Church.

“We’ve got so many people now that have so many different opinions about how things should be. We need to come together and be on one accord,” said Gary, who was a member of Shuttlesworth’s Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights.

“Now, you’ve got demonstrations all over the world, but they’ve got different issues. Ours was a collective effort to end segregation, and that’s what we accomplished at that time. New laws were passed.”

Iva Williams, 49, vice president of the Outcast Voter’s League, said he sees a younger generation that’s “fed up” but in a different way than in the past.

“Millennials have a different outlook,” he said. “It’s a different level of fed up, I think. They just refuse to be held back, if you will. … That’s why it’s incumbent upon guys like myself and … other people … to provide them some boundaries. We have to give them some things to think about. We have to hold them back because … these young people protest a lot differently.”

Some recent demonstrations have involved protests like the one Tuesday evening outside Hoover City Hall after Alabama Attorney General Steve Marshall said a Hoover police officer took justifiable action in the shooting and killing of 21-year-old Emantic “E.J.” Bradford Jr. at the Riverchase Galleria mall on Thanksgiving night.

Protesters have also made visits to the home of Hoover Mayor Frank Brocato and the Montgomery neighborhood of Alabama Attorney General Steve Marshall; and the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute (BCRI) after its board rescinded a decision to present the Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth Human Rights Award, to renowned activist and Birmingham native Angela Davis, PhD—a decision the BCRI has since reversed.

The Rev. Arthur Price, 53, pastor of downtown Birmingham’s Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, said the objective of protests remains to shine a light on injustices and inequity, so “the community at large might be able to see what this small segment of the population sees [and] to make sure they understand the blight that’s going on in the community.

Martez Files, a 27-year-old organizer for the Black Lives Matter movement and an African-American studies professor at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB), said some often forget the goals of the marches, “why we were doing this in the first place,” he said, before Marshall announced his decision on the Bradford, Jr. shooting. “I know you get so caught up in, … ‘I gotta fight.’ ‘I gotta resist.’ ‘I gotta protest.’ ‘I gotta show up.’ … Then we lose [sight of] why we were doing it.”

“Hateful Acts”

In Birmingham 55 years ago, there was no doubt why the protesters marched.

“The enemy in 1963 was very obvious: [Birmingham Commissioner of Public Safety Theophilus “Bull” Connor] and the white establishment. They were the enemy, and they were very vocal and very pronounced in their determination to keep blacks in their place,” said the Rev. Dr. Christopher Hamlin, pastor of Tabernacle Baptist Church in West Birmingham. “Now, the enemies … are not as well-known and obvious as they were in 1963. Those attitudes that were very obvious in 1963 may not be as obvious today, with the exception of the number of African-Americans that have been shot, killed, or gunned down by law enforcement officers.”

In addition to Bradford being shot and killed last year by a Hoover police officer, several other young black men have been killed under suspicious circumstances that generated national attention and outrage, including 17-year-old Trayvon Martin, who was shot and killed in 2012 by a neighborhood watchman in Sanford, Fla.; 18-year-old Michael Brown, who was shot and killed in 2014 by a police officer in Ferguson, Miss.; 12-year-old Tamir Rice, who was killed in 2014 by a law enforcement officer in Cleveland, Ohio; and 32-year-old Philando Castile, who was shot in front of his girlfriend and her daughter in 2016 after being pulled over in Falcon Heights, Minn.

“In terms of beatings or violence, … especially upon African-Americans, they did it then, and we see in some of these cases now that this stuff continues to happen today,” Hamlin said. “In many of these situations, it’s all … racism. Racism breeds, produces, stimulates hateful acts. So, if someone exhibits racism or is a racist, that can come out in multiple ways.

“If you’re a police officer, it could very well be mistreatment of blacks or Hispanics. If you’re a loan officer, it could be to give someone a harder time to try to secure a loan for a home or a car. If you’re a realtor, you might put up a lot of roadblocks if someone wants to move into a certain neighborhood. That stuff continues to happen, unfortunately.”

[/media-credit] Martez Files, a 27-year-old organizer for the Black Lives Matter Movement and an African-American studies professor at UAB.

Lessons Learned

Williams said the younger generation should be careful not to abandon all the principles of the past.

“Sometimes young people almost run away from anything that has been done in the past,” he said. “If our elders did a sit in at a lunch counter, [today’s young people] want to go in and take over the whole lunchroom. … It just seems like they want to take things a step further. Sometimes that’s good, and sometimes that’s very dangerous because their wanting to take things a step further can sometimes challenge the law, and that’s something we are so intent on not doing. … We just want to exercise civil disobedience.”

Gary said there are lessons to be learned from what happened 55 years ago.

The Civil Rights Movement “accomplished what we wanted to accomplish,” she said.

“We were demonstrating against the injustice of segregation, and laws were passed during the times that we demonstrated. … They removed the [separate] water fountains. They removed the … ‘Colored’ and ‘White’ boards from the school buses. They integrated the school systems. [We] were able to get jobs. [We] were able to vote.”

This article originally appeared in The Birmingham Times.

Activism

Oakland Post: Week of November 26 – December 2, 2025

The printed Weekly Edition of the Oakland Post: Week of November 26 – December 2, 2025

To enlarge your view of this issue, use the slider, magnifying glass icon or full page icon in the lower right corner of the browser window.

Activism

Oakland Post: Week of November 19 – 25, 2025

The printed Weekly Edition of the Oakland Post: Week of November 19 – 25, 2025

To enlarge your view of this issue, use the slider, magnifying glass icon or full page icon in the lower right corner of the browser window.

Activism

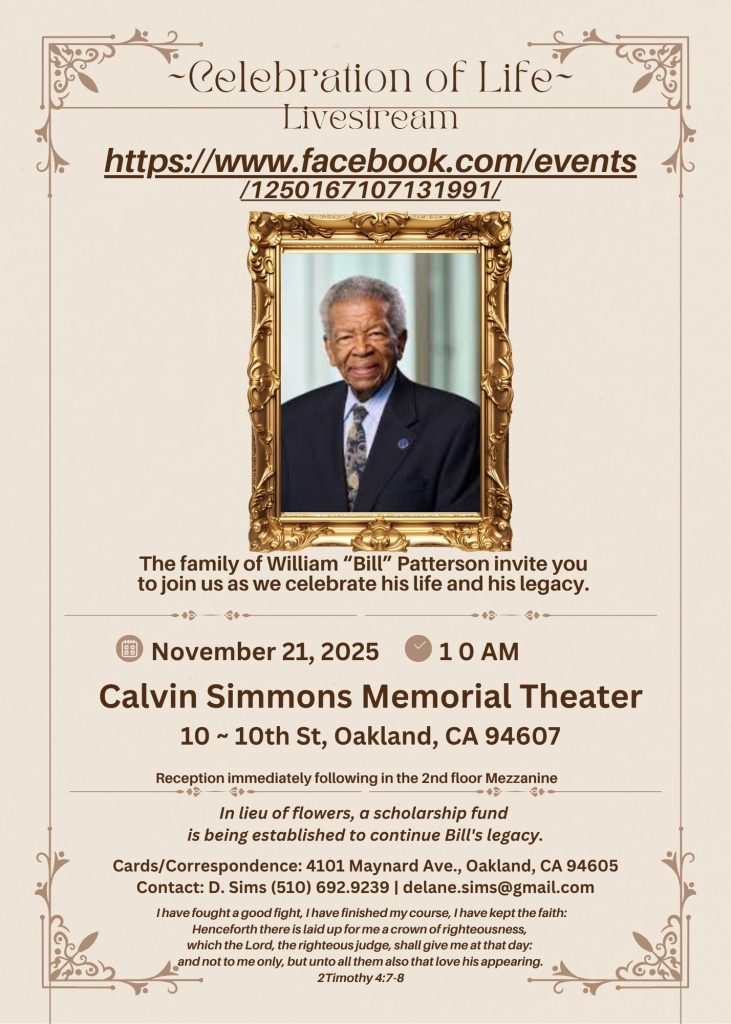

IN MEMORIAM: William ‘Bill’ Patterson, 94

Bill devoted his life to public service and education. In 1971, he became the founding director for the Peralta Community College Foundation, he also became an administrator for Oakland Parks and Recreation overseeing 23 recreation centers, the Oakland Zoo, Children’s Fairyland, Lake Merritt, and the Henry J. Kaiser Convention Center.

William “Bill” Patterson, 94, of Little Rock, Arkansas, passed away peacefully on October 21, 2025, at his home in Oakland, CA. He was born on May 19, 1931, to Marie Childress Patterson and William Benjamin Patterson in Little Rock, Arkansas. He graduated from Dunbar High School and traveled to Oakland, California, in 1948. William Patterson graduated from San Francisco State University, earning both graduate and undergraduate degrees. He married Euradell “Dell” Patterson in 1961. Bill lovingly took care of his wife, Dell, until she died in 2020.

Bill devoted his life to public service and education. In 1971, he became the founding director for the Peralta Community College Foundation, he also became an administrator for Oakland Parks and Recreation overseeing 23 recreation centers, the Oakland Zoo, Children’s Fairyland, Lake Merritt, and the Henry J. Kaiser Convention Center.

He served on the boards of Oakland’s Urban Strategies Council, the Oakland Public Ethics Commission, and the Oakland Workforce Development Board.

He was a three-term president of the Oakland branch of the NAACP.

Bill was initiated in the Gamma Alpha chapter of Kappa Alpha Psi Fraternity.

In 1997 Bill was appointed to the East Bay Utility District Board of Directors. William Patterson was the first African American Board President and served the board for 27 years.

Bill’s impact reached far beyond his various important and impactful positions.

Bill mentored politicians, athletes and young people. Among those he mentored and advised are legends Joe Morgan, Bill Russell, Frank Robinson, Curt Flood, and Lionel Wilson to name a few.

He is survived by his son, William David Patterson, and one sister, Sarah Ann Strickland, and a host of other family members and friends.

A celebration of life service will take place at Henry J. Kaiser Convention Center (Calvin Simmons Theater) on November 21, 2025, at 10 AM.

His services are being livestreamed at: https://www.facebook.com/events/1250167107131991/

In lieu of flowers, donations can be made to the Euradell and William Patterson scholarship fund TBA.

-

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of November 12 – 18, 2025

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoIN MEMORIAM: William ‘Bill’ Patterson, 94

-

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks agoHow Charles R. Drew University Navigated More Than $20 Million in Fed Cuts – Still Prioritizing Students and Community Health

-

Bay Area4 weeks ago

Bay Area4 weeks agoNo Justice in the Justice System

-

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks agoLewis Hamilton set to start LAST in Saturday Night’s Las Vegas Grand Prix

-

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks agoBeyoncé and Jay-Z make rare public appearance with Lewis Hamilton at Las Vegas Grand Prix

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of November 19 – 25, 2025

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoProtecting Pedophiles: The GOP’s Warped Crusade Against Its Own Lies