Business

Where are the Black hemp farmers?

FLORIDA COURIER — Although hemp is legal, regulatory risks complicate the crop’s long-term outlook. Some states are positioning themselves to compete, but it’s unlikely the market can sustain hemp production in every state — unless there’s a significant increase in product demand, according to a February 2019 report from the College of Agriculture, Food and Environment at the University of Kentucky.

By April Simpson

COLUMBIA, Md. – Clarenda Stanley-Anderson will be the featured farmer of Hemp History Week, an educational campaign in June focused on a newly legal crop that’s at the center of a risky, potentially billion-dollar industry.

Stanley-Anderson is considered a pioneer in the nascent hemp agricultural community, for educating others and encouraging young farmers to bring hemp back to the U.S. agrarian landscape, according to history week organizers.

It’ll be the first time that the Hemp Industries Association annual initiative, which boasts celebrity endorsements and events across the country, will feature a non-white farmer.

Stanley-Anderson wants to expand the representation of hemp farmers, even if she’s far from the average industry insider. Black farmers are a mere 1.4 percent of the country’s 3.2 million farmers, according to the 2012 U.S. Department of Agriculture Census of Agriculture.

In North Carolina, where Stanley-Anderson and her husband own Green Heffa Farms in the town of Liberty, Black farm operators are nearly 3 percent of farmers.

While Black farmers aren’t as visible, Stanley-Anderson is part of a developing community. As growers, processors and entrepreneurs, Black professionals across the country are working to carve out a space in a trendy industry that’s projected to reach $1.9 billion in U.S. hemp-based product sales by 2022, according to the Hemp Business Journal, an online publication that tracks the industry.

‘BECOMING EXTINCT’

Individuals and organizations are in the early stages of building networks of Black farmers and processors to ensure Black agriculture professionals get their share of hemp riches. But it’s hard for everyone to take on the risk.

Black farmers have long been discriminated against by lending institutions like the USDA. And with a limited population of growers, land, resources and sometimes access to the information networks that enable farmers to move quickly, they could be left behind again with hemp.

“Black farmers are becoming extinct,” said Lamar Wilson, founder of SunJoined, a nationwide network of hemp growers and processors with farmers in Kentucky, Kansas and Colorado. “This is an opportunity to bring them back and to actually provide a profitable resource, but also a resource that can be used for so many different things.”

Not everyone is optimistic hemp is the future for the small and under-resourced farmer, unless there are regulatory efforts to ensure they can be competitive.

“Most minority farms are on the verge of survival,” said Joe Trigg, a farmer and city council member in Glasgow, Kentucky, who’s running as a Democrat for state commissioner of agriculture. “The last thing they need is something else to drag them down.”

Hemp has been touted by Democratic and Republican senators as a lifeline nationwide to farmers, many of whom are struggling under declining commodity prices. Farmers can harvest three types of hemp: fiber; grain or seed; or floral material extracted for plant resin, including cannabidiol, popularly known as CBD. Hemp’s uses span more than 25,000 products, including textiles, biofuel, ropes, cosmetics, food and beverages.

REGULATORY RISKS

Agriculture professionals say the high-value crop can be particularly well-suited to Black landowners, who typically have smaller farms and less overall sales than White farmers.

Black farmland accounts for 0.4 percent of U.S. farmland, and sales account for 0.2 percent of total U.S. agriculture sales, according to the USDA. Hemp can be cultivated in tight spaces, especially when harvested for fiber and seed, which are planted in narrow rows.

“We’re just seeing Black farmers emerge in the market,” said Bonita Money, founder of the Los Angeles-based National Diversity Inclusion and Cannabis Alliance, another group connecting hemp farmers of color.

Although hemp is legal, regulatory risks complicate the crop’s long-term outlook. Some states are positioning themselves to compete, but it’s unlikely the market can sustain hemp production in every state — unless there’s a significant increase in product demand, according to a February 2019 report from the College of Agriculture, Food and Environment at the University of Kentucky.

“Technology may dictate that production will ultimately be concentrated in relatively few states where hemp can be grown at the lowest cost of production and transported shorter distances for processing,” the report said.

GOT IN EARLY

Some states, including North Carolina and Kentucky, adopted hemp early and began growing it in research or pilot programs prior to Congress’ passage of the 2018 farm bill, which legalized hemp widely.

Before December, when President Donald Trump signed the bill, federal law treated hemp as a quasi-controlled substance because of its relation to marijuana.

Neither Kentucky nor North Carolina tracks the race of growers or processors, according to spokespeople from the states’ departments of agriculture.

With federal legalization, many states are launching hemp pilot programs, transitioning from pilot to large-scale programs, while some are choosing to keep hemp farming illegal. Regardless, competition is increasing as growing hemp becomes more accessible.

Roscoe M. Moore, Jr., a former assistant U.S. surgeon general who attended a recent hemp workshop in Columbia, Maryland, thinks that as more money enters the hemp market, there will be few minorities involved.

MARIJUANA STIGMA

He pointed to the Maryland state law that called on regulators to reflect racial, ethnic and geographic diversity among those licensed to work in the medical marijuana industry. No Black applicant was awarded a grower’s license, according to news reports, and there were no repercussions, Moore said.

“Business relationships are the gold standard for America,” said Moore, who advises several biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies. “Business is based on commerce. There’s not any excuse why we’re not involved, we just haven’t had the experience.”

But even when approached, Black farmers sometimes decline the opportunity. Trigg, the Kentucky city council member, said a state official encouraged him to participate early in Kentucky’s pilot program.

Trigg declined because of the crop’s association with marijuana and law enforcement oversight.

Even though marijuana and hemp are separate strains of cannabis, with hemp having a lower level of tetrahydrocannabinol, or THC — the main psychoactive component in the cannabis plant — farmers like Trigg worried about a stigma in being associated with the crop.

“There was still so much skepticism associated with it, and everyone was worried,” said Trigg, who plans to grow his first hemp plant this year. “You start growing marijuana on your farm and you’re Black?”

WHITE MALE COMMISSION

Stanley-Anderson, whose nickname is Farmer Cee, didn’t initially connect hemp to equity until she didn’t see herself reflected among decision makers. The North Carolina Industrial Hemp Commission, for example, whose nine members develop rules and licensing fee structures for the industry, is all male.

Eight members are White. Two are from law enforcement. None are African American.

Members, who serve as volunteers, are appointed by the governor, commissioner of agriculture and General Assembly. Their selection criteria are written into state law.

“I agree. It’s all White. It’s all male. But that’s the way it was set up,” said commission Chairman Tom Melton, also deputy director of the North Carolina Cooperative Extension Service at North Carolina State University. “Maybe the law needs to change to indicate some sort of representation. That’s beyond the scope of our commission.”

Federal law requires applicants for hemp licenses to not have had a drug felony in the past 10 years. The advocacy groups Vote Hemp, Drug Policy Alliance and others were able to get that decreased from a lifetime ban, but were unsuccessful in getting removed, said Eric Steenstra, president of Vote Hemp, in an email to Stateline.

“Our goal is to allow all farmers who want to grow hemp to do so with as limited restrictions as possible,” Steenstra wrote. Vote Hemp, based in Washington, D.C., is a national nonprofit advocacy organization that supports a free market for industrial hemp.

BACKGROUND CHECKS

For some Black farmers, the felony restriction on hemp is a lost opportunity. Blacks and Latinos are far more likely to have marijuana-related drug felonies, according to the Drug Policy Alliance.

People coming out of prison desperately need jobs, said Ashley Smith, co-founder of Black Soil: Our Better Nature, an organization that supports Black farmers, growers and producers in Kentucky.

“There has to be some compromise where we can bring folks who are in need of jobs working land that is in need of labor,” Smith said. In Kentucky, hemp laborers are subject to background checks.

Some places are trying a system to offer some restitution for the disproportionate impact of drug enforcement on Black communities.

Some California cities, for example, have adopted cannabis equity programs that provide business development, loan assistance and mentorships for minority and low-income entrepreneurs. Oakland has permits set aside for people of color.

“No one is doing that with hemp,” said Stanley-Anderson, who grew up on a farm in Alabama.

ORLANDO ADVOCACY GROUP

Jackson Garth, national director for industrial hemp for Minorities for Medical Marijuana, an advocacy group based in Orlando, has been working to get equity goals or requirements written into hemp legislation in Georgia and South Carolina. While the measures never made it into legislation, he’s encouraged South Carolina has awarded licenses to farmers of color he’s worked with.

“We’re going to have to have set-asides for Black and brown farmers, so farmers aren’t forgotten,” Garth said.

Garth’s group, known as M4MM, is in the early stages of setting up a co-op program for hemp. Garth, who’s also an executive of an industrial hemp processing company in Atlanta, is educating farmers on the crop and helping them get licenses.

“A lot of times,” Garth said, “it’s a lack of information that we’re receiving, and even when we get the information, it’s too late.”

FARMER EQUITY ACT

At least two states — Illinois and California — have enacted a Farmer Equity Act in recent years to ensure socially disadvantaged farmers and ranchers are included in food and agriculture laws.

States with programs to support minority-owned businesses, new and beginning farmers and other targeted groups, could potentially apply to commercial industrial hemp producers unless there are restrictions in place to exclude hemp production, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

Some critics argue that these programs can feel like a Band-Aid.

“There’s a slew of people who fall under minority,” said Kentucky farmer Charles Jones, citing White women, veterans and other farmers of color. “So, they can say they’re doing this for minorities, but the Black farmer still gets left out within this.”

More than 100 people attended the recent daylong hemp informational event organized by Morgan State University, a historically Black university in Baltimore, Maryland. A handful of the attendees were Black. Among them, few were farmers. Instead, most were entrepreneurs or academics connected to Morgan State.

This article originally appeared in the Florida Courier.

Activism

Books for Ghana

We effectively facilitated cross-continent community building! We met the call and provided 400 books for ASC’s students at the call of the Minister of Education. We supported the work of a new African writer whose breakout novel is an action-packed depiction of a young woman steeped in Ghanaian culture who travels to the USA for college, all the while experiencing the twists, turns, and uncertainties that life brings.

By Min. Rauna Thurston, Chief Mpuntuhene Afua Ewusiwa I

My travels to Afrika began in June 2022, on a tour led by Prof. Manu Ampim, Director of the organization Advancing The Research. I was scheduled to become an ordained Minister by Wo’se Community of the Sacred African Way. It was vital that my feet touch the soil of Kemet and my spirit connect with the continent’s people before ordination.

Since 2022, I’ve made six trips to Afrika. During my travels, I became a benefactor to Abeadze State College (ASC) in Abeadze Dominase, Ghana, originally founded by Daasebre Kwebu Ewusi VII, Paramount Chief of Abeadze Traditional Area and now run by the government. The students there were having trouble with English courses, which are mandatory. The Ghanaian Minister of Education endorsed a novel written by 18-year-old female Ghanaian first-time writer, Nhyira Esaaba Essel, titled Black Queen Sceptre. The idea was that if the students had something more interesting to read, it would evoke a passion for reading; this seemed reasonable to me. Offer students something exciting and imaginative, combined with instructors committed to their success and this could work.

The challenge is how to acquire 800 books?!

I was finishing another project for ASC, so my cash was thin and I was devoid of time to apply for annual grants. I sat on my porch in West Oakland, as I often do, when I’m feeling for and connecting to my ancestors. On quiet nights, I reminisce about the neighborhood I grew up in. Across the street from my house was the house that my Godfather, Baba Dr. Wade Nobles and family lived in, which later became The Institute for the Advanced Study of Black Family Life & Culture (IASBFLC). Then, it came to me…ancestors invited me to reach out to The Association of Black Psychologists – Bay Area Chapter (ABPsi-Bay Area)! It was a long shot but worth it!

I was granted an audience with the local ABPsi Board, who ultimately approved funding for the book project with a stipulation that the Board read the book and a request to subsequently offer input as to how the book would be implemented at ASC. In this moment, my memory jet set to my first ABPsi convention around 2002, while working for IASBFLC. Returning to the present, I thought, “They like to think because it feels good, and then, they talk about what to do about what they think about.” I’m doomed.

However, I came to understand why reading the book and offering suggestions for implementation were essential. In short: ABPsi is an organization that operates from the aspirational principles of Ma’at with aims of liberating the Afrikan Mind, empowering the Afrikan character, and enlivening: illuminating the Afrikan spirit. Their request resulted in a rollout of 400 books in a pair-share system. Students checked out books in pairs, thereby reducing our bottom line to half of the original cost because we purchased 50% fewer units. This nuance promoted an environment of Ujima (collective work & responsibility) and traditional Afrikan principles of cooperation and interdependence. The student’s collaborative approach encouraged shared responsibility, not only for the physical book but for each other’s success. This concept was Dr. Lawford Goddard’s, approved by the Board, with Dr. Patricia “Karabo” Nunley at the helm.

We effectively facilitated cross-continent community building! We met the call and provided 400 books for ASC’s students at the call of the Minister of Education. We supported the work of a new African writer whose breakout novel is an action-packed depiction of a young woman steeped in Ghanaian culture who travels to the USA for college, all the while experiencing the twists, turns, and uncertainties that life brings. (A collectible novel for all ages). A proposed future phase of this collaborative project is for ASC students to exchange reflective essays on Black Queen Sceptre with ABPsi Bay Area members.

We got into good trouble. To order Black Queen Sceptre, email esselewurama14@gmail.com.

I became an ordained Minister upon returning from my initial pilgrimage to Afrika. Who would have imagined that my travels to Afrika would culminate in me becoming a citizen of Sierra Leone and recently being named a Chief Mpuntuhene under Daasebre Kwebu Ewusi VII, Paramount Chief of Abeadze Traditional Area in Ghana, where I envision continued collaborations.

Min. Rauna/Chief Mpuntuhene is a member of ABPsi Bay Area, a healing resource committed to providing the Post Newspaper readership with monthly discussions about critical issues in Black Mental Health, Wealth & Wellness. Readers are welcome to join us at our monthly chapter meetings every 3rd Saturday via Zoom and contact us at bayareaabpsi@gmail.com.

Black History

Alice Parker: The Innovator Behind the Modern Gas Furnace

Born in Morristown, New Jersey, in 1895, Alice Parker lived during a time when women, especially African American women, faced significant social and systemic barriers. Despite these challenges, her contributions to home heating technology have had a lasting impact.

By Tamara Shiloh

Alice Parker was a trailblazing African American inventor whose innovative ideas forever changed how we heat our homes.

Born in Morristown, New Jersey, in 1895, Parker lived during a time when women, especially African American women, faced significant social and systemic barriers. Despite these challenges, her contributions to home heating technology have had a lasting impact.

Parker grew up in New Jersey, where winters could be brutally cold. Although little is documented about her personal life, her education played a crucial role in shaping her inventive spirit. She attended Howard University, a historically Black university in Washington, D.C., where she may have developed her interest in practical solutions to everyday challenges.

Before Parker’s invention, most homes were heated using wood or coal-burning stoves. These methods were labor-intensive, inefficient, and posed fire hazards. Furthermore, they failed to provide even heating throughout a home, leaving many rooms cold while others were uncomfortably warm.

Parker recognized the inefficiency of these heating methods and imagined a solution that would make homes more comfortable and energy-efficient during winter.

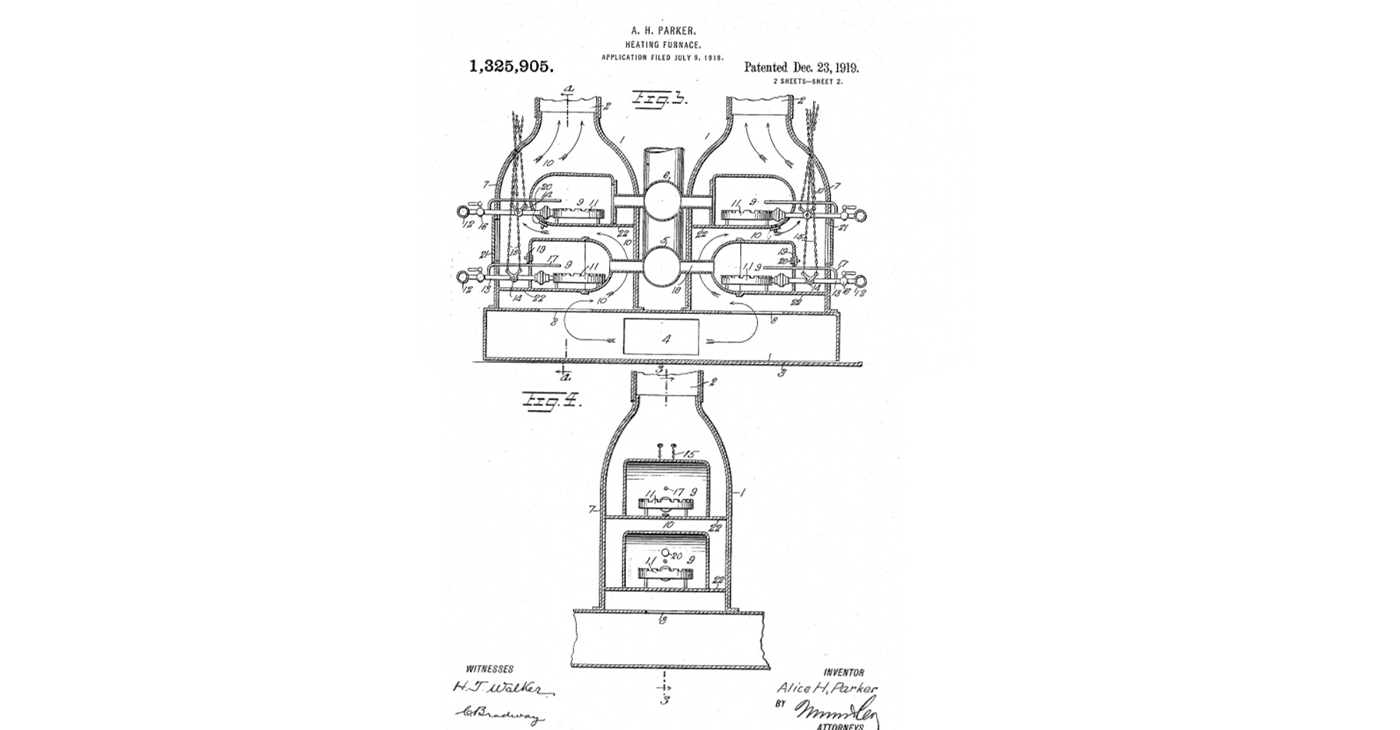

In 1919, she patented her design for a gas-powered central heating system, a groundbreaking invention. Her design used natural gas as a fuel source to distribute heat throughout a building, replacing the need for wood or coal. The system allowed for thermostatic control, enabling homeowners to regulate the temperature in their homes efficiently.

What made her invention particularly innovative was its use of ductwork, which channeled warm air to different parts of the house. This concept is a precursor to the modern central heating systems we use today.

While Parker’s design was never fully developed or mass-produced during her lifetime, her idea laid the groundwork for modern central heating systems. Her invention was ahead of its time and highlighted the potential of natural gas as a cleaner, more efficient alternative to traditional heating methods.

Parker’s patent is remarkable not only for its technical innovation but also because it was granted at a time when African Americans and women faced severe limitations in accessing patent protections and recognition for their work. Her success as an inventor during this period is a testament to her ingenuity and determination.

Parker’s legacy lives on in numerous awards and grants – most noticeably in the annual Alice H. Parker Women Leaders in Innovation Award. That distinction is given out by the New Jersey Chamber of Commerce to celebrate outstanding women innovators in Parker’s home state.

The details of Parker’s later years are as sketchy as the ones about her early life. The specific date of her death, along with the cause, are also largely unknown.

Activism

2024 in Review: Seven Questions for Frontline Doulas

California Black Media (CBM) spoke with Frontline Doulas’ co-founder Khefri Riley. She reflected on Frontline’s accomplishments this year and the organization’s goals moving forward.

By Edward Henderson, California Black Media

Frontline Doulas provides African American families non-medical professional perinatal services at no cost.

This includes physical, emotional, informational, psychosocial and advocacy support during the pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum period. Women of all ages — with all forms of insurance — are accepted and encouraged to apply for services.

California Black Media (CBM) spoke with co-founder Khefri Riley. She reflected on Frontline’s accomplishments this year and the organization’s goals moving forward.

Responses have been edited for clarity and length.

Looking back at 2024, what stands out to you as your most important achievement and why?

In 2024, we are humbled to have been awarded the contract for the Los Angeles County Medical Doula Hub, which means that we are charged with creating a hub of connectivity and support for generating training and helping to create the new doula workforce for the medical doula benefit that went live in California on Jan. 1, 2023.

How did your leadership and investments contribute to improving the lives of Black Californians?

We believe that the revolution begins in the womb. What we mean by that is we have the potential and the ability to create intentional generational healing from the moment before a child was conceived, when a child was conceived, during this gestational time, and when a child is born.

And there’s a traditional saying in Indigenous communities that what we do now affects future generations going forward. So, the work that we do with birthing families, in particular Black birthing families, is to create powerful and healthy outcomes for the new generation so that we don’t have to replicate pain, fear, discrimination, or racism.

What frustrated you the most over the last year?

Working in reproductive justice often creates a heavy burden on the organization and the caregivers who deliver the services most needed to the communities. So, oftentimes, we’re advocating for those whose voices are silenced and erased, and you really have to be a warrior to stand strong and firm.

What inspired you the most over the last year?

My great-grandmother. My father was his grandmother’s midwife assistant when he was a young boy. I grew up with their medicine stories — the ways that they healed the community and were present to the community, even amidst Jim Crow.

What is one lesson you learned in 2024 that will inform your decision-making next year?

I find that you have to reach for your highest vision, and you have to stand firm in your value. You have to raise your voice, speak up and demand, and know your intrinsic value.

In a word, what is the biggest challenge Black Californians face?

Amplification. We cannot allow our voices to be silent.

What is the goal you want to achieve most in 2025?

I really would like to see a reduction in infant mortality and maternal mortality within our communities and witness this new birth worker force be supported and integrated into systems. So, that way, we fulfill our goal of healthy, unlimited birth in the Black community and indeed in all birthing communities in Los Angeles and California.

-

California Black Media4 weeks ago

California Black Media4 weeks agoCalifornia to Offer $43.7 Million in Federal Grants to Combat Hate Crimes

-

Black History4 weeks ago

Black History4 weeks agoEmeline King: A Trailblazer in the Automotive Industry

-

California Black Media4 weeks ago

California Black Media4 weeks agoGov. Newsom Goes to Washington to Advocate for California Priorities

-

California Black Media4 weeks ago

California Black Media4 weeks agoCalifornia Department of Aging Offers Free Resources for Family Caregivers in November

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of November 27 – December 3, 2024

-

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks agoOCCUR Hosts “Faith Forward” Conference in Oakland

-

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks agoRichmond Seniors Still Having a Ball After 25 Years

-

Activism2 weeks ago

Activism2 weeks agoButler, Lee Celebrate Passage of Bill to Honor Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm with Congressional Gold Medal