Arts and Culture

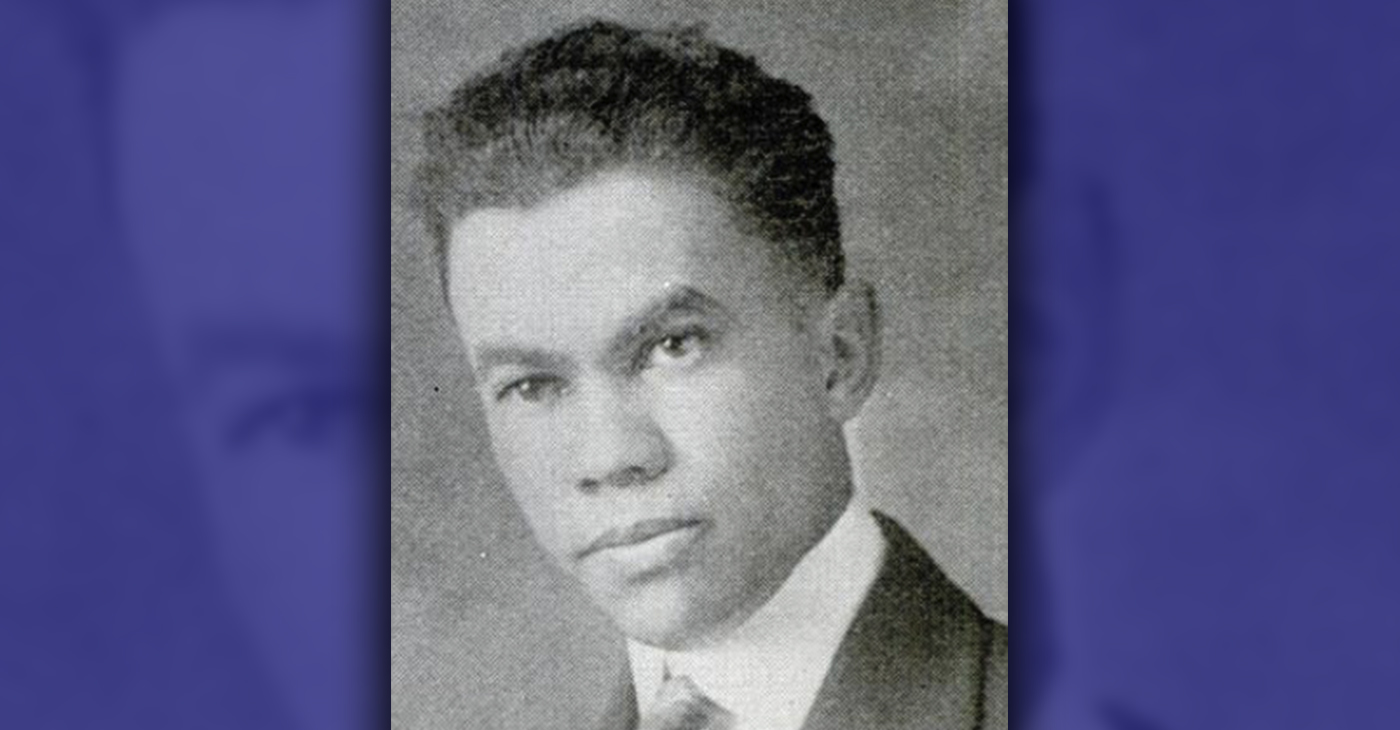

‘Architect to the Stars,’ Paul R. Williams Helped Define L.A.’s Building Style

Among his many remarkable buildings are the opulent Saks Fifth Avenue building in Beverly Hills and the flying saucer–shaped Theme Building at the Los Angeles International Airport (as co-designer). He also oversaw additions to the Beverly Hills Hotel in the 1950s. In addition to stores, public housing, hotels, and restaurants, he designed showrooms, churches, and schools.

By Tamara Shiloh

Paul Revere Williams (1894-1980) was an African American architect noted for his mastery of a variety of styles and building types and for his influence on the architectural landscape of Southern California.

In more than 3,000 buildings over the course of five decades, mostly in and around Los Angeles, he introduced a sense of casual elegance that came to define the region’s architecture. His work became so popular with Hollywood royalty that he was known as the “architect to the stars.”

Williams, the second of two children, was born in 1894, shortly after his parents moved to Los Angeles from Memphis, Tenn. Both his parents died by the time he was four years old, and Williams was reared by a family friend while his brother lived with a different family.

Because his foster mother quickly recognized his talent, Williams received a solid education and followed his dream to become an architect, though there were few African American architects at the time.

His architectural aspirations remained uppermost in his thoughts. He attended the Los Angeles atelier of the Beaux-Arts Institute of Design (1913–16) and was certified as an architect in 1915.

While attending a program for architectural engineering at the University of Southern California from 1916-1919, he took a series of low-paying jobs at several architectural firms to learn as much as he could.

He learned about landscape architecture while working with Wilbur D. Cook and got his first taste of designing on a palatial scale at the firm of Reginald D. Johnson. From 1920 to 1922, he worked for John C. Austin (with whom he later collaborated), turning his attention to designs for large public buildings.

In 1921, Williams received a license to practice architecture in California and accepted his first commission from Louis Cass, a white, former high school classmate.

A year later, at age 28, Williams founded his own business, Paul R. Williams and Associates, and in 1923 he became the first African American member of the American Institute of Architects. He later was licensed to practice in Wash., D.C. (1936), New York (1948), Tennessee (1960), and Nevada (1964).

His designs for suburban and country estates incorporated Mediterranean, Spanish Revival, and English Tudor themes, a blend of styles that strongly appealed to California residents at mid-century. No matter what their stylistic elements, his houses were impeccably designed down to the smallest detail, and they were airy, sun-filled, and graceful.

As Williams’ reputation grew, he received commissions to design houses for such Hollywood stars as Lon Chaney, Lucille Ball, Frank Sinatra, Bill (‘Bojangles’) Robinson, Barbara Stanwyck, Cary Grant, Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall and Anthony Quinn.

Among his many remarkable buildings are the opulent Saks Fifth Avenue building in Beverly Hills and the flying saucer–shaped Theme Building at the Los Angeles International Airport (as co-designer). He also oversaw additions to the Beverly Hills Hotel in the 1950s. In addition to stores, public housing, hotels, and restaurants, he designed showrooms, churches, and schools.

After 1950, when Modernism and its most-predominant architectural manifestation, the International Style, began to hold sway, Williams was seen as an architect of traditional (that is, old-fashioned) designs.

His gift for accommodating eclectic tastes while obeying sound design principles was seen as a drawback. But public taste eventually came full circle, and Williams-designed homes, especially, were again in demand in the early 21st century.

Williams wrote a number of articles, notably “I Am a Negro” (1937) for The American Magazine, and two books, “The Small Home of Tomorrow” (1945) and “New Homes for Today” (1946). In 1953, he was awarded the NAACP Spingarn Medal. Many awards and honors followed, both during and after his lifetime.

Sources: https://www.npr.org/2012/06/22/155442524/a-trailblazing-black-architect-who-helped-shape-l-a

Arts and Culture

Book Review: Building the Worlds That Kill Us: Disease, Death, and Inequality in American History

Nearly five years ago, while interviewing residents along the Mississippi River in Louisiana for a book they were writing, authors Rosner and Markowitz learned that they’d caused a little brouhaha. Large corporations in the area, ones that the residents of “a small, largely African American community” had battled over air and soil contamination and illness, didn’t want any more “’agitators’” poking around. They’d asked a state trooper to see if the authors were going to cause trouble.

By Terri Schlichenmeyer

Author: David Rosner and Gerald Markowitz, c.2024, Columbia University Press, $28.00

Get lots of rest.

That’s always good advice when you’re ailing. Don’t overdo. Don’t try to be Superman or Supermom, just rest and follow your doctor’s orders.

And if, as in the new book, “Building the Worlds That Kill Us” by David Rosner and Gerald Markowitz, the color of your skin and your social strata are a certain way, you’ll feel better soon.

Nearly five years ago, while interviewing residents along the Mississippi River in Louisiana for a book they were writing, authors Rosner and Markowitz learned that they’d caused a little brouhaha. Large corporations in the area, ones that the residents of “a small, largely African American community” had battled over air and soil contamination and illness, didn’t want any more “’agitators’” poking around. They’d asked a state trooper to see if the authors were going to cause trouble.

For Rosner and Markowitz, this underscored “what every thoughtful person at least suspects”: that age, geography, immigrant status, “income, wealth, race, gender, sexuality, and social position” largely impacts the quality and availability of medical care.

It’s been this way since Europeans first arrived on North American shores.

Native Americans “had their share of illness and disease” even before the Europeans arrived and brought diseases that decimated established populations. There was little-to-no medicine offered to slaves on the Middle Passage because a ship owner’s “financial calculus… included the price of disease and death.” According to the authors, many enslavers weren’t even “convinced” that the cost of feeding their slaves was worth the work received.

Factory workers in the late 1800s and early 1900s worked long weeks and long days under sometimes dangerous conditions, and health care was meager; Depression-era workers didn’t fare much better. Black Americans were used for medical experimentation. And just three years ago, the American Lung Association reported that “’people of color’ disproportionately” lived in areas where the air quality was particularly dangerous.

So, what does all this mean? Authors David Rosner and Gerald Markowitz don’t seem to be too optimistic, for one thing, but in “Building the Worlds That Kill Us,” they do leave readers with a thought-provoker: “we as a nation … created this dark moment and we have the ability to change it.” Finding the “how” in this book, however, will take serious between-the-lines reading.

If that sounds ominous, it is. Most of this book is, in fact, quite dismaying, despite that there are glimpses of pushback here and there, in the form of protests and strikes throughout many decades. You may notice, if this is a subject you’re passionate about, that the histories may be familiar but deeper than you might’ve learned in high school. You’ll also notice the relevance to today’s healthcare issues and questions, and that’s likewise disturbing.

This is by no means a happy-happy vacation book, but it is essential reading if you care about national health issues, worker safety, public attitudes, and government involvement in medical care inequality. You may know some of what’s inside “Building the Worlds That Kill Us,” but now you can learn the rest.

Arts and Culture

‘Giants Rising’ Film Screening in Marin City Library

A journey into the heart of America’s most iconic forests, “Giants Rising” tells the epic tale of the coast redwoods — the tallest and among the oldest living beings on Earth. Living links to the past, redwoods hold powers that may play a role in our future, including their ability to withstand fire and capture carbon, to offer clues about longevity, and to enhance our own well-being.

By Godfrey Lee

The film “Giants Rising” will be screened on Saturday, Jan. 11, from 3-6 p.m. at the St. Andrew Presbyterian Church, located 100 Donahue St. in Marin City.

A journey into the heart of America’s most iconic forests, “Giants Rising” tells the epic tale of the coast redwoods — the tallest and among the oldest living beings on Earth. Living links to the past, redwoods hold powers that may play a role in our future, including their ability to withstand fire and capture carbon, to offer clues about longevity, and to enhance our own well-being.

Through the voices of scientists, artists, Native communities, and others, we discover the many connections that sustain these forests and the promise of solutions that will help us all rise up to face the challenges that lay ahead.

The film’s website is www.giantsrising.com. The “Giants Rising” trailer is at https://player.vimeo.com/video/904153467. The registration link to the event is https://marinlibrary.bibliocommons.com/events/673de7abb41279410057889e

This event is sponsored by the Friends of the Marin City Library and hosted in conjunction with the Golden Gate National Recreation Area and St. Andrew Presbyterian Church.

All library events are free. For more information, contact Etienne Douglas at (415) 332-6158 or email etienne.douglas@marincounty.gov. For event-specific information, contact Zaira Sierra at zsierra@parksconservancy.org.

Activism

‘Resist’ a Look at Black Activism in U.S. Through the Eyes of a Native Nigerian

In 1995, after she and her brothers traveled from their native Nigeria to join their mother at her new home in the South Bronx, young Omokha’s eyes were opened. She quickly understood that the color of her skin – which was “synonymous with endless striving and a pursuit of excellence” in Nigeria – was “so problematic in America.”

By Terri Schlichenmeyer, The Bookworm Sez

Throughout history, when decisions were needed, the answer has often been “no.”

‘No,’ certain people don’t get the same education as others. ‘No,’ there is no such thing as equality. ‘No,’ voting can be denied and ‘no,’ the laws are different, depending on the color of one’s skin. And in the new book, “Resist!” by Rita Omokha, ‘no,’ there is not an obedient acceptance of those things.

In 1995, after she and her brothers traveled from their native Nigeria to join their mother at her new home in the South Bronx, young Omokha’s eyes were opened. She quickly understood that the color of her skin – which was “synonymous with endless striving and a pursuit of excellence” in Nigeria – was “so problematic in America.”

That became a bigger matter to Omokha later, 15 years after her brother was deported: she “saw” him in George Floyd, and it shook her. Troubled, she traveled to America on a “pilgrimage for understanding [her] Blackness…” She began to think about the “Black young people across America” who hadn’t been or wouldn’t be quiet about racism any longer.

She starts this collection of stories with Ella Josephine Baker, whose parents and grandparents modeled activism and who, because of her own student activism, would be “crowned the mother of the Civil Rights Movement.” Baker, in fact, was the woman who formed the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, or SNCC, in 1960.

Nine teenagers, known as the Scottsboro Nine were wrongly arrested for raping two white women in 1931 and were all released, thanks to the determination of white lawyer-allies who were affiliated with the International Labor Defense and the outrage of students on campuses around America.

Students refused to let a “Gentleman’s Agreement” pass when it came to sports and equality in 1940. Barbara Johns demanded equal education under the law in Virginia in 1951. Huey Newton and Bobby Seale formed the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense in 1966. And after Trayvon Martin (2012) and George Floyd (2020) were killed, students used the internet as a new form of fighting for justice.

No doubt, by now, you’ve read a lot of books about activism. There are many of them out there, and they’re pretty hard to miss. With that in mind, there are reasons not to miss “Resist!”

You’ll find the main one by looking between the lines and in each chapter’s opening.

There, Omokha weaves her personal story in with that of activists at different times through the decades, matching her experiences with history and making the whole timeline even more relevant.

In doing so, the point of view she offers – that of a woman who wasn’t totally raised in an atmosphere filled with racism, who wasn’t immersed in it her whole life – lets these historical accounts land with more impact.

This book is for people who love history or a good, short biography, but it’s also excellent reading for anyone who sees a need for protest or action and questions the status quo. If that’s the case, then “Resist!” may be the answer.

“Resist! How a Century of Young Black Activists Shaped America” by Rita Omokha, c.2024, St. Martin’s Press. $29.00

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoBooks for Ghana

-

Arts and Culture4 weeks ago

Arts and Culture4 weeks agoPromise Marks Performs Songs of Etta James in One-Woman Show, “A Sunday Kind of Love” at the Black Repertory Theater in Berkeley

-

Bay Area3 weeks ago

Bay Area3 weeks agoGlydways Breaking Ground on 14-Acre Demonstration Facility at Hilltop Mall

-

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks ago‘Donald Trump Is Not a God:’ Rep. Bennie Thompson Blasts Trump’s Call to Jail Him

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoLiving His Legacy: The Late Oscar Wright’s “Village” Vows to Inherit Activist’s Commitment to Education

-

Arts and Culture3 weeks ago

Arts and Culture3 weeks agoIn ‘Affrilachia: Testimonies,’ Puts Blacks in Appalacia on the Map

-

Alameda County3 weeks ago

Alameda County3 weeks agoAC Transit Holiday Bus Offering Free Rides Since 1963

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoCalifornia, Districts Try to Recruit and Retain Black Teachers; Advocates Say More Should Be Done