Opinion

Opinion: Oakland Needs Good Jobs; Can We Trust Uber to Provide Them?

When The Greenlining Institute joined with other Oaklanders to launch a campaign for Uber to take responsibility for its business practices in Oakland, we got lots of attention — including widespread media coverage and over 1,500 visitors to the campaign website in just the first two days — but also some criticism.

Some of that criticism came from people correctly pointing out that Oakland urgently needs good jobs, and that criticism deserves a response.

One person, for example, wrote:

“We should be joyous that companies want to locate here… How else are jobs going to be created here except by encouraging businesses to locate here?”

Everyone wants good jobs for Oaklanders. And that’s exactly why we need to hold companies like Uber accountable.

Orson Aguilar

From what Uber has said, the company seems likely to employ 200-300 people at first, and possibly many more later. Right now, there’s no guarantee that even one of those jobs will go to anyone who actually lives in Oakland.

If Uber imports workers from Silicon Valley or recruits them from universities where few Oakland students attend, Oaklanders will gain nothing.

Actually, that’s not true. An imported Uber workforce will leave Oaklanders worse off, because those imported, highly-paid workers will compete with Oakland residents for increasingly scarce and pricey housing. And the pressure Uber’s arrival has already put on commercial rents is already costing our city lots of nonprofit jobs that traditionally have belonged to people who live here.

That’s why the Uber community campaign has put jobs front and center. We’ve asked Uber to make concrete, measurable commitments to recruit and hire local workers — both current residents and those who’ve already been driven out by skyrocketing housing costs.

We’ve asked Uber to invest in the training of local workers and students by supporting “pipeline programs” to train Oakland adults and young people for meaningful careers at Uber and other tech companies coming into the area.

And we’ve asked Uber to help preserve and expand the jobs provided by existing Oakland-based businesses by thinking proactively about what vendors it contracts with.

All large companies need to buy lots of goods and services, and Uber will be no exception. If those contracts go to local businesses, that means more jobs for local workers and a stronger homegrown business community.

We agree with our critics that Uber could be good for Oakland, but only if it chooses to act in partnership with Oakland’s residents and businesses.

If it comes in like an invading force — which, to be honest, has been Uber’s business model as it expands its ride-hailing service into new territories — it will leave our city’s workers worse off, not better.

Gay Plair Cobb

No one wants to turn away companies that could bring jobs to our town, but all we have to do is look across the bay to San Francisco to see what happens when a tech boom includes no social responsibility: Rents and evictions soar, wealthy tech workers displace the nurses, teachers, cooks and plumbers who form the backbone of our communities, and longtime residents end up worse off or get forced out entirely.

No sane person wants that kind of future for Oakland.

A real Oakland jobs agenda must include a meaningful commitment to the local workforce by Uber and other major corporations coming into our city. If you support a real jobs agenda in Oakland, please join us.

Orson Aguilar is president of The Greenlining Institute. Gay Plair Cobb is CEO of Oakland Private Industry Council, Inc.

Activism

2025 in Review: Seven Questions for Assemblymember Lori Wilson — Advocate for Equity, the Environment, and More

Her rise has also included several historic firsts: she is the only Black woman ever appointed to lead the influential Assembly Transportation Committee, and the first freshman legislator elected Chair of the California Legislative Black Caucus. She has also been a vocal advocate for vulnerable communities, becoming the first California legislator to publicly discuss being the parent of a transgender child — an act of visibility that has helped advanced representation at a time when political tensions related to social issues and culture have intensified.

By Edward Henderson, California Black Media

Assemblymember Lori D. Wilson (D-Suisun City) joined the California Legislature in 2022 after making history as Solano County’s first Black female mayor, bringing with her a track record of fiscal discipline, community investment, and inclusive leadership.

She represents the state’s 11th Assembly District, which spans Solano County and portions of Contra Costa and Sacramento Counties.

Her rise has also included several historic firsts: she is the only Black woman ever appointed to lead the influential Assembly Transportation Committee, and the first freshman legislator elected Chair of the California Legislative Black Caucus. She has also been a vocal advocate for vulnerable communities, becoming the first California legislator to publicly discuss being the parent of a transgender child — an act of visibility that has helped advanced representation at a time when political tensions related to social issues and culture have intensified.

California Black Media spoke with Wilson about her successes and disappointments this year and her outlook for 2026.

What stands out as your most important achievement this year?

Getting SB 237 passed in the Assembly. I had the opportunity to co-lead a diverse workgroup of colleagues, spanning a wide range of ideological perspectives on environmental issues.

How did your leadership contribute to improving the lives of Black Californians this year?

The Black Caucus concentrated on the Road to Repair package and prioritized passing a crucial bill that remained incomplete during my time as chair, which establishes a process for identifying descendants of enslaved people for benefit eligibility.

What frustrated you the most this year?

The lack of progress made on getting Prop 4 funds allocated to socially disadvantaged farmers. This delay has real consequences. These farmers have been waiting for essential support that was promised. Watching the process stall, despite the clear need and clear intent of the voters, has been deeply frustrating and reinforces how much work remains to make our systems more responsive and equitable.

What inspired you the most this year?

The resilience of Californians persists despite the unprecedented attacks from the federal government. Watching people stay engaged, hopeful, and determined reminded me why this work matters and why we must continue to protect the rights of every community in our state.

What is one lesson you learned this year that will inform your decision-making next year?

As a legislator, I have the authority to demand answers to my questions — and accept nothing less. That clarity has strengthened my approach to oversight and accountability.

In one word, what is the biggest challenge Black Californians are facing currently?

Affordability and access to quality educational opportunities.

What is the goal you want to achieve most in 2026?

Advance my legislative agenda despite a complex budget environment. The needs across our communities are real, and even in a tight fiscal year, I’m committed to moving forward policies that strengthen safety, expand opportunity, and improve quality of life for the people I represent.

Activism

2025 in Review: Seven Questions for Assemblymember Tina McKinnor, Champion of Reparations, Housing and Workers’ Rights

In 2025, McKinnor pushed forward legislation on renters’ protections, re-entry programs, reparations legislation, and efforts to support Inglewood Unified School District. She spoke with California Black Media about the past year and her work. Here are her responses.

By Joe W. Bowers Jr., California Black Media

Assemblymember Tina McKinnor (D-Inglewood) represents

California’s 61st Assembly District.

As a member of the California Legislative Black Caucus (CLBC),

McKinnor was elected in 2022. She chairs the Los Angeles County Legislative Delegation and leads the Assembly Public Employment and Retirement Committee. McKinnor also served as a civic engagement director, managed political campaigns, and worked as chief of staff for former Assemblymembers Steven Bradford and Autumn Burke.

In 2025, McKinnor pushed forward legislation on renters’ protections, re-entry programs, reparations legislation, and efforts to support Inglewood Unified School District. She spoke with California Black Media about the past year and her work. Here are her responses.

Looking back on 2025, what do you see as your biggest win?

Assembly Bill (AB) 628. If rent is $3,000, people should at least have a stove and a refrigerator. It’s ridiculous that people were renting without basic appliances.

I’m also proud that I was able to secure $8.4 million in the state budget for people coming home from incarceration. That includes the Homecoming Project, the menopause program for incarcerated women, and the Justice Leaders Program.

How did your leadership help make life better for Black Californians this year?

After the Eaton Fire, I pushed to get the same kind of support for affected areas that wealthier regions get after disasters.

I also did a lot of work building political power— establishing the Black Legacy PAC and California for All of Us PAC so we could support Black candidates and educate voters. We also called voters to make sure they understood Prop 50.

People need to understand this: there are only 12 Black legislators in the Capitol. Folks act like we can just walk in and pass reparations, but that’s not how it works.

What frustrated you most this year?

The governor did not have the political will to sign these bills: AB 57 and AB 62. They both passed overwhelmingly in the Assembly and the Senate. We did the work. The only person who didn’t have the political will to sign them was the governor.

The public needs to ask the governor why he didn’t sign the bills. We can’t keep letting people off the hook. He has to answer.

I also introduced AB 51 — the bill to eliminate interest payments on Inglewood Unified School District’s long-standing state loan — held in the Appropriations Committee. That was frustrating,

What inspired you most in 2025?

The civil rights trip to Alabama was life changing. We visited the Legacy Museum and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice. We took members of the Black, Latino, Jewish, and API caucuses with us. It changed all of us.

People aren’t always against us — they just don’t know our history.

What’s one lesson from 2025 that will shape how you approach decisions next year?

The legislative trip to Norway taught me that collaboration matters. Government, labor, and industry sit down together there. They don’t make villains. Everybody doesn’t get everything they want, but they solve problems.

What’s the biggest challenge facing Black Californians in one word?

Inequity. It shows up in housing, wealth, stress – all these things.

What’s the number one goal you want to accomplish in 2026?

Bringing back AB 57 and AB 62, and securing money for the Inglewood Unified loan interest forgiveness.

Advice

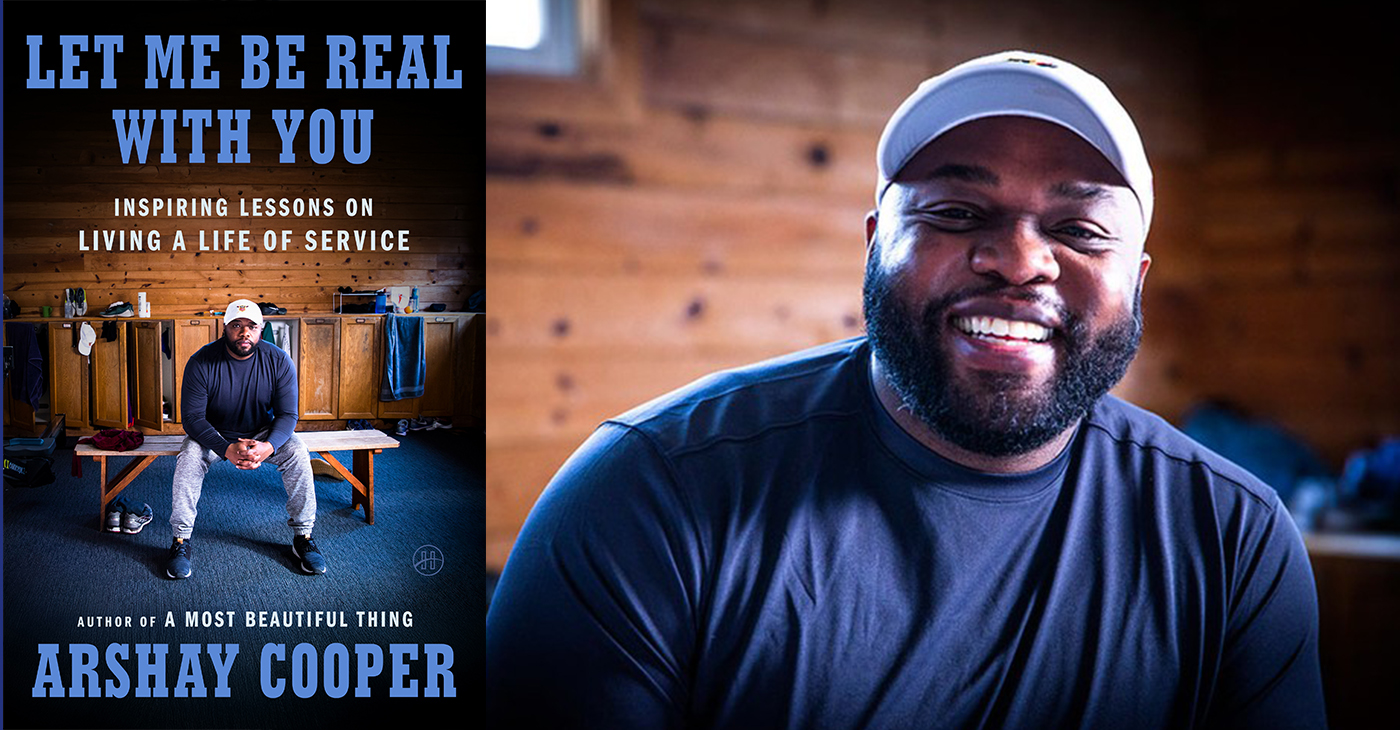

BOOK REVIEW: Let Me Be Real With You

At first look, this book might seem like just any other self-help offering. It’s inspirational for casual reader and business reader, both, just like most books in this genre. Dig a little deeper, though, and you’ll spot what makes “Let Me Be Real With You” stand out.

By Terri Schlichenmeyer

Author: Arshay Cooper, Copyright: c.2025, Publisher: HarperOne, SRP: $26.00, Page Count: 40 Pages

The hole you’re in is a deep one.

You can see the clouds above, and they look like a storm; you sense the wind, and it’s cold. It’s dark down there, and lonesome, too. You feel like you were born there — but how do you get out of the deep hole you’re in? You read the new book “Let Me Be Real With You” by Arshay Cooper. You find a hand-up and bring someone with you.

In the months after his first book was published, Cooper received a lot of requests to speak to youth about his life growing up on the West Side of Chicago, his struggles, and his many accomplishments. He was poor, bullied, and belittled, but he knew that if he could escape those things, he would succeed. He focused on doing what was best, and right. He looked for mentors and strove to understand when opportunities presented themselves.

Still, his early life left him with trauma. Here, he shows how it’s overcome-able.

We must always have hope, Cooper says, but hope is “merely the catalyst for action. The hope we receive must transform into the hope we give.”

Learn to tell your own story, as honestly as you know it. Be open to suggestions, and don’t dismiss them without great thought. Know that masculinity doesn’t equal stoicism; we are hard-wired to need other people, and sharing “pain and relatability can dissipate shame and foster empathy in powerful ways.”

Remember that trauma is intergenerational, and it can be passed down from parent to child. Let your mentors see your potential. Get therapy, if you need it; there’s no shame in it, and it will help, if you learn to trust it. Enjoy the outdoors when you can. Learn self-control. Give back to your community. Respect your financial wellness. Embrace your intelligence. Pick your friends and relationships wisely. “Do it afraid.”

And finally, remember that “You were born to soar to great heights and rule the sky.”

You just needed someone to tell you that.

At first look, this book might seem like just any other self-help offering. It’s inspirational for casual reader and business reader, both, just like most books in this genre. Dig a little deeper, though, and you’ll spot what makes “Let Me Be Real With You” stand out.

With a willingness to discuss the struggles he tackled in the past, Cooper writes with a solidly honest voice that’s exceptionally believable, and not one bit dramatic. You won’t find unnecessarily embellished stories or tall tales here, either; Cooper instead uses his real experiences to help readers understand that there are few things that are truly insurmountable. He then explains how one’s past can shape one’s future, and how today’s actions can change the future of the world.

“Let Me Be Real With You” is full of motivation, and instruction that’s do-able for adults and teens. If you need that, or if you’ve vowed to do better this coming year, it might help make you whole.

-

Alameda County4 weeks ago

Alameda County4 weeks agoSeth Curry Makes Impressive Debut with the Golden State Warriors

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoLIHEAP Funds Released After Weeks of Delay as States and the District Rush to Protect Households from the Cold

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoSeven Steps to Help Your Child Build Meaningful Connections

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoSeven Steps to Help Your Child Build Meaningful Connections

-

Bay Area2 weeks ago

Bay Area2 weeks agoPost Salon to Discuss Proposal to Bring Costco to Oakland Community meeting to be held at City Hall, Thursday, Dec. 18

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks agoFBI Report Warns of Fear, Paralysis, And Political Turmoil Under Director Kash Patel

-

Activism2 weeks ago

Activism2 weeks agoMayor Lee, City Leaders Announce $334 Million Bond Sale for Affordable Housing, Roads, Park Renovations, Libraries and Senior Centers

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of December 10 – 16, 2025