Black History

Malvin Russell: Goode Black Radio Reporter Who Covered Cuban Missile Crisis

Malvin Russell Goode (1908–1995) ignored the cultural roadblocks preventing minorities from entering and having success in the field of journalism.

By Tamara Shiloh

About 80% of Black adults expect that national news stories will be accurate. About 53% feel connected to their main news source overall. One in three say they have a lot of trust in the information they get from local news organizations. These facts aside, Black people have historically been underrepresented in the newsroom.

Malvin Russell Goode (1908–1995) ignored the cultural roadblocks preventing minorities from entering and having success in the field of journalism.

After graduating from the University of Pittsburgh in 1931, Goode continued his employment as a steelworker for five years. He then worked at various jobs: a probation officer, director for the YMCA, manager for the Pittsburgh Housing Authority, and eventually in the public relations department of the Pittsburgh Courier, where, at age 40, he moved into the position of reporter.

He later took a leap into radio broadcasting, beginning with a 15-minute, twice-weekly commentary for KQV Radio in Pittsburgh. His popularity began to soar.

After 13 years in broadcasting, Goode was hired by ABC in 1962, making him the national news network’s first African American correspondent. He dove at the chance to present all sides of news coverage.

Seven weeks into Goode’s network career, the Cuban Missile Crisis developed. The lead ABC correspondent for the United Nations was on vacation, so Goode reported on the entire story for the network. He continued to cover the U.N. until his retirement in 1973.

Throughout his career, Goode also reported on political conventions, and civil and human rights issues during the 1960s.

Goode was jailed many times in attempts to harass and intimidate him for his involvement with civil rights issues. He was active with the NAACP and traveled across the country to give speeches for more than 200 local chapters.

He knew and interviewed many prominent civil rights leaders and athletes such as Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, and Jackie Robinson.

Post retirement, he worked for the National Black Network, again covering the U.N., civil rights, and politics, a move that proved challenging.

Goode was born in White Plains, Va. His grandparents had once been slaves, and their history informed Goode’s entire family life, giving them ambition and determination.

His mother attended West Virginia State University, and often stressed the importance of education to her children. Goode would remember these lessons for the rest of his life. This can be seen by his determination and his interest in events that affected the world.

About Goode, former ABC anchor Peter Jennings, who considered him a mentor, once said: “Mal could have very sharp elbows. If he was on a civil rights story and anyone even appeared to give him any grief because he was black, he made it more than clear that this was now a free country.”

Goode died of a stroke on Sept. 12, 1995, in Pittsburgh.

Activism

Oakland Post: Week of November 26 – December 2, 2025

The printed Weekly Edition of the Oakland Post: Week of November 26 – December 2, 2025

To enlarge your view of this issue, use the slider, magnifying glass icon or full page icon in the lower right corner of the browser window.

Activism

Oakland Post: Week of November 19 – 25, 2025

The printed Weekly Edition of the Oakland Post: Week of November 19 – 25, 2025

To enlarge your view of this issue, use the slider, magnifying glass icon or full page icon in the lower right corner of the browser window.

Activism

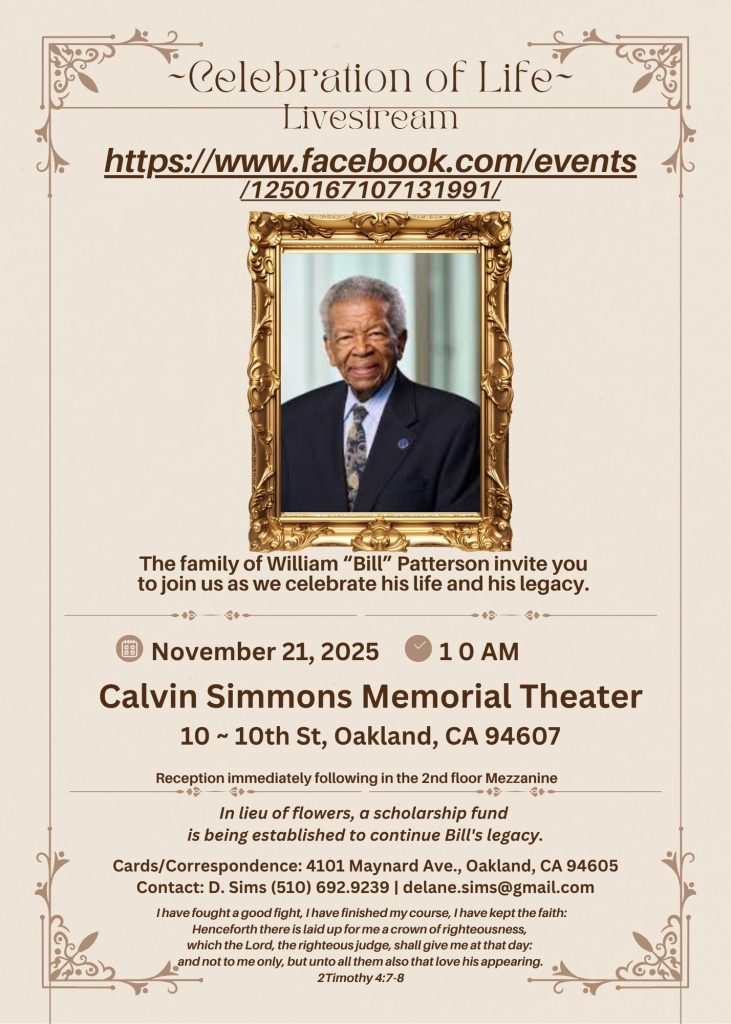

IN MEMORIAM: William ‘Bill’ Patterson, 94

Bill devoted his life to public service and education. In 1971, he became the founding director for the Peralta Community College Foundation, he also became an administrator for Oakland Parks and Recreation overseeing 23 recreation centers, the Oakland Zoo, Children’s Fairyland, Lake Merritt, and the Henry J. Kaiser Convention Center.

William “Bill” Patterson, 94, of Little Rock, Arkansas, passed away peacefully on October 21, 2025, at his home in Oakland, CA. He was born on May 19, 1931, to Marie Childress Patterson and William Benjamin Patterson in Little Rock, Arkansas. He graduated from Dunbar High School and traveled to Oakland, California, in 1948. William Patterson graduated from San Francisco State University, earning both graduate and undergraduate degrees. He married Euradell “Dell” Patterson in 1961. Bill lovingly took care of his wife, Dell, until she died in 2020.

Bill devoted his life to public service and education. In 1971, he became the founding director for the Peralta Community College Foundation, he also became an administrator for Oakland Parks and Recreation overseeing 23 recreation centers, the Oakland Zoo, Children’s Fairyland, Lake Merritt, and the Henry J. Kaiser Convention Center.

He served on the boards of Oakland’s Urban Strategies Council, the Oakland Public Ethics Commission, and the Oakland Workforce Development Board.

He was a three-term president of the Oakland branch of the NAACP.

Bill was initiated in the Gamma Alpha chapter of Kappa Alpha Psi Fraternity.

In 1997 Bill was appointed to the East Bay Utility District Board of Directors. William Patterson was the first African American Board President and served the board for 27 years.

Bill’s impact reached far beyond his various important and impactful positions.

Bill mentored politicians, athletes and young people. Among those he mentored and advised are legends Joe Morgan, Bill Russell, Frank Robinson, Curt Flood, and Lionel Wilson to name a few.

He is survived by his son, William David Patterson, and one sister, Sarah Ann Strickland, and a host of other family members and friends.

A celebration of life service will take place at Henry J. Kaiser Convention Center (Calvin Simmons Theater) on November 21, 2025, at 10 AM.

His services are being livestreamed at: https://www.facebook.com/events/1250167107131991/

In lieu of flowers, donations can be made to the Euradell and William Patterson scholarship fund TBA.

-

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of November 5 – 11, 2025

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of November 12 – 18, 2025

-

Activism2 weeks ago

Activism2 weeks agoIN MEMORIAM: William ‘Bill’ Patterson, 94

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoHow Charles R. Drew University Navigated More Than $20 Million in Fed Cuts – Still Prioritizing Students and Community Health

-

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks agoThe Perfumed Hand of Hypocrisy: Trump Hosted Former Terror Suspect While America Condemns a Muslim Mayor

-

Bay Area3 weeks ago

Bay Area3 weeks agoNo Justice in the Justice System

-

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks agoProtecting Pedophiles: The GOP’s Warped Crusade Against Its Own Lies

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago2026 Subaru Forester Wilderness Review: Everyday SUV With Extra Confidence