Alameda County

Pamela Price: The Path to the District Attorney’s Office is No Crystal Stair, Part I

When civil rights attorney Pamela Price decided to run for Alameda County District Attorney, her life was already the personification of poet Langston Hughes’ famous poem “Mother to Son” that notes that “Life Ain’t No Crystal Stair.” Price comes from the type of community she ran for office to serve. She was once on the other side of the law and is an example of how people can change when given the opportunity.

By Tanya Dennis

When civil rights attorney Pamela Price decided to run for Alameda County District Attorney, her life was already the personification of poet Langston Hughes’ famous poem “Mother to Son” that notes that “Life Ain’t No Crystal Stair.”

Price comes from the type of community she ran for office to serve. She was once on the other side of the law and is an example of how people can change when given the opportunity.

Raised in Cincinnati, Ohio, Price states she was traumatized, then radicalized with the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. at age 11. Raised in group homes and foster care homes, Price describes her childhood as traumatic.

“Raised in group homes and foster care, at age 13 I was in a juvenile justice facility. I walked away from foster care at age 16 to my own accountability, living all over the place,” she recalled. “I rented a truck, went back to my three foster homes, collected the little I possessed, and checked into a ‘fleabag’ hotel that I could pay for by the week. Despite the adversity, I not only survived, I thrived. “

Price attributes her ability to thrive to foster moms who “kept their hands on her,” stressing the importance of education as the only true path to liberation.

Managing to graduate from high school, Price got accepted to Yale College on a full scholarship. That scholarship, according to Price, was the game changer. She majored in political science and American studies, and after graduating from Law School, became a civil rights attorney.

In 2017, while working with the Contra Costa County Racial Justice Coalition on a number of racial issues around police misconduct, they were successful in getting Contra Costa County District Attorney Mark Peterson to resign in disgrace and admit to felonies, which open the door for a new D.A..

People asked Price to run for D.A. in Contra Costa County, but she refused because she lived in Alameda County. When she declined, a young man responded, “Alameda is just as bad.” Upon investigation, Price realized he was right, and no one had challenged Alameda County District Attorney Nancy O’Malley in four years.

In June of 2017, Price began her campaign for D.A. in Alameda County, but she lost in 2018.

Still determines, then ran again in 2022 and won.

Walking into the office on January 3, Price describes an office in total disarray.

According to Price, there were employees with no supervisor, a myriad of unfilled positions despite money set aside, people on payroll making substantial amounts of money who were not working.

And that was just the start, she said. “The computer system was antiquated; no method of communication existed between offices in the nine locations; no human resource for 450 employees and no operational plans or processes in place.”

Standards of accountability were lacking and “absolutely no working oversight.”

The most serious issue she faced, she said, were employees traumatized by fellow members suicides and heart attacks. They were in deep need of mental support.

“The culture in that office was toxic and addressing their trauma was my first priority. I’m happy to report that 90% of the staff stayed.”

After addressing the health and wellness of her employees, the victim witness advocates were next. Price noted that “The DA’s office was understaffed across the entire spectrum despite O’Malley having the funds: she didn’t manage this organization at all.”

Knowing that people voted for her to get the DA’s office in order, Price says the last three months restructuring the office has been formidable but cites a 25% improvement.

Despite best intents, her efforts were thwarted after she placed people on leave, and they became disgruntled and started attacking her office.

Taking on the culture of the organization, Price hired 35 people to fill vacancies, created a management structure, and addressed dramatic overpayments to some the people who have since have been placed in their correct positions.

Responsible for nine locations, the systemic failure in communications makes Price’s vision of transforming the DA’s office a formidable task, but one she says she’s up to.

“It will take wisdom, patience, grace, courage, compassion, and a sense of purpose with a real commitment to serve the people of Alameda County. I was put in this season for a reason, and I’ve been preparing all my life for this.”

Next Week: Part 2 – A New Vision of Justice.

Alameda County

Seth Curry Makes Impressive Debut with the Golden State Warriors

Seth looked comfortable in his new uniform, seamlessly fitting into the Warriors’ offensive and defensive system. He finished the night with an impressive 14 points, becoming one of the team’s top scorers for the game. Seth’s points came in a variety of ways – floaters, spot-up three-pointers, mid-range jumpers, and a handful of aggressive drives that kept the Oklahoma City Thunder defense on its heels.

By Y’Anad Burrell

Tuesday night was anything but ordinary for fans in San Francisco as Seth Curry made his highly anticipated debut as a new member of the Golden State Warriors. Seth didn’t disappoint, delivering a performance that not only showcased his scoring ability but also demonstrated his added value to the team.

At 35, the 12-year NBA veteran on Monday signed a contract to play with the Warriors for the rest of the season.

Seth looked comfortable in his new uniform, seamlessly fitting into the Warriors’ offensive and defensive system. He finished the night with an impressive 14 points, becoming one of the team’s top scorers for the game. Seth’s points came in a variety of ways – floaters, spot-up three-pointers, mid-range jumpers, and a handful of aggressive drives that kept the Oklahoma City Thunder defense on its heels.

One of the most memorable moments of the evening came before Seth even scored his first points. As he checked into the game, the Chase Center erupted into applause, with fans rising to their feet to give the newest Warrior a standing ovation.

The crowd’s reaction was a testament not only to Seth’s reputation as a sharpshooter but also to the excitement he brings to the Warriors. It was clear that fans quickly embraced Seth as one of their own, eager to see what he could bring to the team’s championship aspirations.

Warriors’ superstar Steph Curry – Seth’s brother – did not play due to an injury. One could only imagine what it would be like if the Curry brothers were on the court together. Magic in the making.

Seth’s debut proved to be a turning point for the Warriors. Not only did he contribute on the scoreboard, but he also brought a sense of confidence and composure to the floor.

While their loss last night, OKC 124 – GSW 112, Seth’s impact was a game-changer and there’s more yet to come. Beyond statistics, it was clear that Seth’s presence elevated the team’s performance, giving the Warriors a new force as they look to make a deep playoff run.

Activism

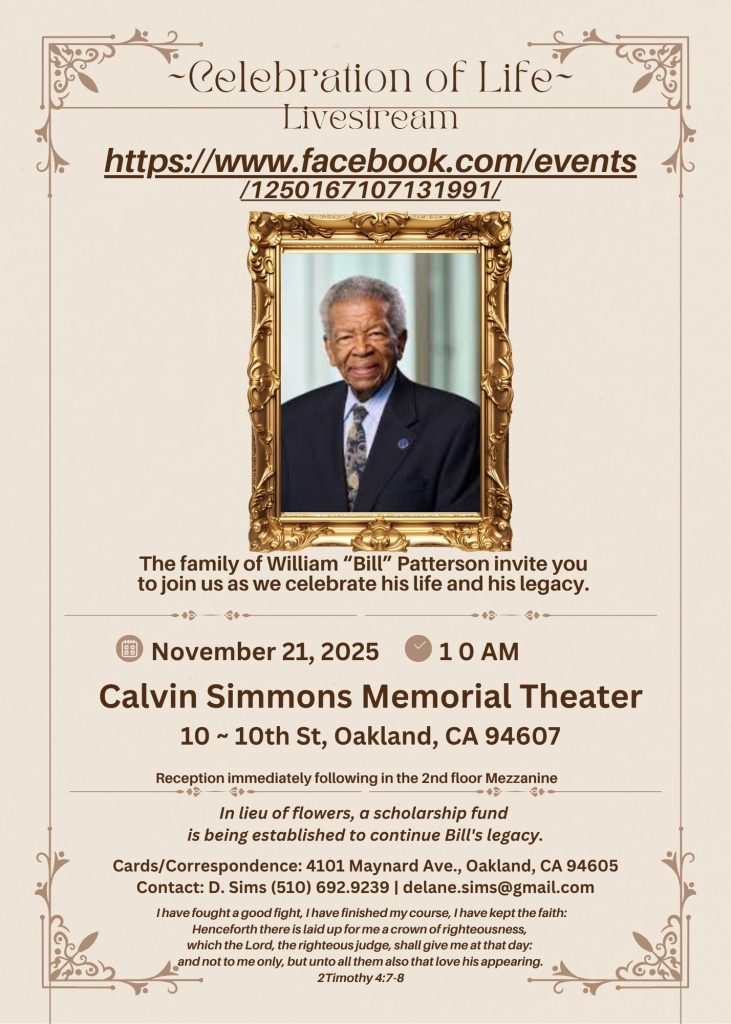

IN MEMORIAM: William ‘Bill’ Patterson, 94

Bill devoted his life to public service and education. In 1971, he became the founding director for the Peralta Community College Foundation, he also became an administrator for Oakland Parks and Recreation overseeing 23 recreation centers, the Oakland Zoo, Children’s Fairyland, Lake Merritt, and the Henry J. Kaiser Convention Center.

William “Bill” Patterson, 94, of Little Rock, Arkansas, passed away peacefully on October 21, 2025, at his home in Oakland, CA. He was born on May 19, 1931, to Marie Childress Patterson and William Benjamin Patterson in Little Rock, Arkansas. He graduated from Dunbar High School and traveled to Oakland, California, in 1948. William Patterson graduated from San Francisco State University, earning both graduate and undergraduate degrees. He married Euradell “Dell” Patterson in 1961. Bill lovingly took care of his wife, Dell, until she died in 2020.

Bill devoted his life to public service and education. In 1971, he became the founding director for the Peralta Community College Foundation, he also became an administrator for Oakland Parks and Recreation overseeing 23 recreation centers, the Oakland Zoo, Children’s Fairyland, Lake Merritt, and the Henry J. Kaiser Convention Center.

He served on the boards of Oakland’s Urban Strategies Council, the Oakland Public Ethics Commission, and the Oakland Workforce Development Board.

He was a three-term president of the Oakland branch of the NAACP.

Bill was initiated in the Gamma Alpha chapter of Kappa Alpha Psi Fraternity.

In 1997 Bill was appointed to the East Bay Utility District Board of Directors. William Patterson was the first African American Board President and served the board for 27 years.

Bill’s impact reached far beyond his various important and impactful positions.

Bill mentored politicians, athletes and young people. Among those he mentored and advised are legends Joe Morgan, Bill Russell, Frank Robinson, Curt Flood, and Lionel Wilson to name a few.

He is survived by his son, William David Patterson, and one sister, Sarah Ann Strickland, and a host of other family members and friends.

A celebration of life service will take place at Henry J. Kaiser Convention Center (Calvin Simmons Theater) on November 21, 2025, at 10 AM.

His services are being livestreamed at: https://www.facebook.com/events/1250167107131991/

In lieu of flowers, donations can be made to the Euradell and William Patterson scholarship fund TBA.

Activism

Past, Present, Possible! Oakland Residents Invited to Reimagine the 980 Freeway

Organizers ask attendees coming to 1233 Preservation Park Way to think of the event as a “time portal”—a walkable journey through the Past (harm and flourishing), Present (community conditions and resilience), and Future (collective visioning).

By Randolph Belle

Special to The Post

Join EVOAK!, a nonprofit addressing the historical harm to West Oakland since construction of the 980 freeway began in 1968, will hold a block party on Oct. 25 at Preservation Park for a day of imagination and community-building from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m.

Organizers ask attendees coming to 1233 Preservation Park Way to think of the event as a “time portal”—a walkable journey through the Past (harm and flourishing), Present (community conditions and resilience), and Future (collective visioning).

Activities include:

- Interactive Visioning: Site mapping, 3-D/digital modeling, and design activities to reimagine housing, parks, culture, enterprise, and mobility.

- Story & Memory: Oral history circles capturing life before the freeway, the rupture it caused, and visions for repair.

- Data & Policy: Exhibits on health, environment, wealth impacts, and policy discussions.

- Culture & Reflection: Films, installations, and performances honoring Oakland’s creativity and civic power.

The site of the party – Preservation Park – itself tells part of the story of the impact on the community. Its stately Victorians were uprooted and relocated to the site decades ago to make way for the I-980 freeway, which displaced hundreds of Black families and severed the heart of West Oakland. Now, in that same space, attendees will gather to reckon with past harms, honor the resilience that carried the community forward, and co-create an equitable and inclusive future.

A Legacy of Resistance

In 1979, Paul Cobb, publisher of the Post News Group and then a 36-year-old civil-rights organizer, defiantly planted himself in front of a bulldozer on Brush Street to prevent another historic Victorian home from being flattened for the long-delayed I-980 Freeway. Refusing to move, Cobb was arrested and hauled off in handcuffs—a moment that landed him on the front page of the Oakland Tribune.

Cobb and his family had a long history of fighting for their community, particularly around infrastructure projects in West Oakland. In 1954, his family was part of an NAACP lawsuit challenging the U.S. Post Office’s decision to place its main facility in the neighborhood, which wiped out an entire community of Black residents.

In 1964, they opposed the BART line down Seventh Street—the “Harlem of the West.” Later, Cobb was deeply involved in successfully rerouting the Cypress Freeway out of the neighborhood after the Loma Prieta earthquake.

The 980 Freeway, a 1.6-mile stretch, created an ominous barrier severing West Oakland from Downtown. Opposition stemmed from its very existence and the national practice of plowing freeways through Black communities with little input from residents and no regard for health, economic, or social impacts. By the time Cobb stood before the bulldozer, construction was inevitable, and his fight shifted toward jobs and economic opportunity.

Fast-forward 45 years: Cobb recalled the story at a convening of “Super OGs” organized to gather input from legacy residents on reimagining the corridor. He quickly retrieved his framed Tribune front page, adding a new dimension to the conversation about the dedication required to make change. Themes of harm repair and restoration surfaced again and again, grounded in memories of a thriving, cohesive Black neighborhood before the freeway.

The Lasting Scar

The 980 Freeway was touted as a road to prosperity—funneling economic opportunity into the City Center, igniting downtown commerce, and creating jobs. Instead, it cut a gash through the city, erasing 503 homes, four churches, 22 businesses, and hundreds of dreams. A promised second approach to the Bay Bridge never materialized.

Planning began in the late 1940s, bulldozers arrived in 1968, and after years of delays and opposition, the freeway opened in 1985. By then, Oakland’s economic engines had shifted, leaving behind a 600-foot-wide wound that resulted in fewer jobs, poorer health outcomes, and a divided neighborhood. The harm of displacement and loss of generational wealth was compounded through redlining, disinvestment, drugs, and the police state. Many residents fled to outlying cities, while those who stayed carried forward the spirit of perseverance.

The Big Picture

At stake now is up to 67 acres of new, buildable land in Downtown West Oakland. This time, we must not repeat the institutional wrongs of the past. Instead, we must be as deliberate in building a collective, equitable vision as planners once were in destroying communities.

EVOAK!’s strategy is rooted in four pillars: health, housing, economic development, and cultural preservation. These were the very foundations stripped away, and they are what they aim to reclaim. West Oakland continues to suffer among the worst social determinants of health in the region, much of it linked to the three freeways cutting through the neighborhood.

The harms of urban planning also decimated cultural life, reinforced oppressive public safety policies, underfunded education, and fueled poverty and blight.

Healing the Wound

West Oakland was once the center of Black culture during the Great Migration—the birthplace of the Black Panther Party and home to the “School of Champions,” the mighty Warriors of McClymonds High. Drawing on that legacy, we must channel the community’s proud past into a bold, community-led future that restores connection, sparks innovation, and uplifts every resident.

Two years ago, Caltrans won a federal Reconnecting Communities grant to fund Vision 980, a community-driven study co-led by local partners. Phase 1 launched in Spring 2024 with surveys and outreach; Phase 2, a feasibility study, begins in 2026. Over 4,000 surveys have already been completed. This once-in-a-lifetime opportunity could transform the corridor into a blank slate—making way for accessible housing, open space, cultural facilities, and economic opportunity for West Oakland and the entire region.

Leading with Community

In parallel, EVOAK! is advancing a community-led process to complement Caltrans’ work. EVOAK! is developing a framework for community power-building, quantifying harm, exploring policy and legislative repair strategies, structuring community governance, and hosting arts activations to spark collective imagination. The goal: a spirit of co-creation and true collaboration.

What EVOAK! Learned So Far

Through surveys, interviews, and gatherings, residents have voiced their priorities: a healthy environment, stable housing, and opportunities to thrive. Elders with decades in the neighborhood shared stories of resilience, community bonds, and visions of what repair should look like.

They heard from folks like Ezra Payton, whose family home was destroyed at Eighth and Brush streets; Ernestine Nettles, still a pillar of civic life and activism; Tom Bowden, a blues man who performed on Seventh Street as a child 70 years ago; Queen Thurston, whose family moved to West Oakland in 1942; Leo Bazille who served on the Oakland City Council from 1983 to 1993; Herman Brown, still organizing in the community today; Greg Bridges, whose family’s home was picked up and moved in the construction process; Martha Carpenter Peterson, who has a vivid memory of better times in West Oakland; Sharon Graves, who experienced both the challenges and the triumphs of the neighborhood; Lionel Wilson, Jr., whose family were anchors of pre-freeway North Oakland; Dorothy Lazard, a resident of 13th Street in the ’60s and font of historical knowledge; Bishop Henry Williams, whose simple request is to “tell the truth,” James Moree, affectionately known as “Jimmy”; the Flippin twins, still anchored in the community; and Maxine Ussery, whose father was a business and land owner before redlining.

EVOAK! will continue to capture these stories and invites the public to share theirs as well.

Beyond the Block Party

The 980 Block Party is just the beginning. Beyond this one-day event, EVOAK! Is building a long-term process to ensure West Oakland’s future is shaped by those who lived its past. To succeed, EVOAK! Is seeking partners across the community—residents, neighborhood associations, faith groups, and organizations—to help connect with legacy residents and host conversations.

980 Block Party Event Details

Saturday, Oct. 25

10 a.m. – 4 p.m.

Preservation Park, 1233 Preservation Park Way, Oakland, CA 94612

980BlockParty.org

info@evoak.org

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of November 12 – 18, 2025

-

Activism4 weeks ago

Activism4 weeks agoOakland Post: Week of November 5 – 11, 2025

-

Activism2 weeks ago

Activism2 weeks agoIN MEMORIAM: William ‘Bill’ Patterson, 94

-

Activism3 weeks ago

Activism3 weeks agoHow Charles R. Drew University Navigated More Than $20 Million in Fed Cuts – Still Prioritizing Students and Community Health

-

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks agoThe Perfumed Hand of Hypocrisy: Trump Hosted Former Terror Suspect While America Condemns a Muslim Mayor

-

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress3 weeks agoProtecting Pedophiles: The GOP’s Warped Crusade Against Its Own Lies

-

Bay Area3 weeks ago

Bay Area3 weeks agoNo Justice in the Justice System

-

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago

#NNPA BlackPress4 weeks ago2026 Subaru Forester Wilderness Review: Everyday SUV With Extra Confidence